After years of discovery, development, and deployment, uptake of 3D and DPC (digital product creation) tools is growing – from core design and development processes, to downstream use cases. But despite wide-scale 3D adoption, apparel go-to-market calendars have stayed largely unchanged.

What can brands do to reclaim the time that’s being left on the table? The Interline partnered with Clothing Tech® – whose FashionrTM “4D Clothing Creator” is designed to compress time from sketch to retail shelf – to explore why time to market has remained so static, and what might need to happen to change it.

In fashion, the case for better tools has always been made based on their ability to shorten the distance between idea and reality. From the earliest historic inventions to the relentless pursuit of efficiency that fuelled the industrial revolution, innovation and improvement in making clothing has always been a steady pushing-back of the envelope between a new creative idea or an unmet need, and the time, the effort, the equipment, and the degree of compromise required to bring it to life.

The rise of 3D tools and workflows in apparel has been no different. Building on top of everything that’s gone before – from flat digital sketching to material scanning – 3D solutions, and the wider digital product creation (DPC) ecosystem that has grown around them, have been positioned as the latest and best way to bring creative design, development, engineering, fit, marketing and a spectrum of other processes into closer alignment.

Today, few brands have not at least experimented with 3D in either creative and technical design or, at the opposite end of the value chain, in consumer-facing sales and marketing, as a stand-in for product photography. 3D design, simulation, and visualisation, and the marketplace and ecosystem of tools and services that feed them, are now being billed – and accepted and adopted – as the next logical progression in a long history of better tools, and also hailed as a revolutionary rethink of what it means to create clothing.

But, as the apparel sector enters an era of relative 3D maturity, how far has that revolution actually been realised? And has this changeover of tools really translated into an overhaul of the core mechanics of product design, development, and production?

To begin, it’s important to note that, from an industry-agnostic perspective, creating and visualising products in 3D is not a novel or experimental idea. In fact, fashion is one of the last product-centric industries to make the move from two-dimensional sketching to 3D design. In other sectors like automotive, aerospace, furniture, and consumer electronics, 3D drafting has been the de facto standard for some time.

In those industries, where absolute 3D maturity is higher, this transition has also demonstrably underpinned a fundamental change to the way products and components make it to the market. By swapping a process of 2D drawing for 3D computer aided design (CAD) those sectors have documented marked improvements to speed, automation, accuracy and efficiency, as well as unlocking the vital ability for 3D assets to serve as full product definitions, and to directly drive production. The average chair, for example, is not just visualised and designed in 3D as part of a cross-dimensional workflow – that 3D model effectively is the product until the point at which it’s manufactured.

Fashion has not reached the same level. A large-scale roll-out of 3D tools has improved accuracy and efficiency, cut waste, and improved fit, as well as making it possible to more comprehensively and flexibly visualise new ideas, experiment with new options, and market to retail partners and consumers with renders in place of photographs. But by and large, despite widespread uptake of 3D and DPC tools, workflows, and solutions, the apparel sector still moves new products from concept to retail through the same sequential processes and in roughly the same amount of time as it did before the transition from 2D to 3D.

For the average brand, no matter how deep they are in their DPC journey, 3D may have saved days, or perhaps a week or two, from their timelines. But the overall shape, scope, and structure of their calendars are likely to have remained essentially untouched.

So why the discrepancy between fashion and other sectors? The key lies is understanding the difference in the utility of 3D assets. In those other industries, the vast majority of components and finished goods (upwards of 90% in the automotive and aerospace sectors) are not just visualised in 3D as a way of representing or bringing to life a 2D sketch or pattern, but are natively designed, developed, engineered and refined that way – with the 3D asset also being the sole touchpoint for capturing and communicating materials, specifications, dimensions, labour operations, and much more.

In apparel, those additional elements reside beyond the 3D asset, and live beyond the immediate DPC ecosystem. As a result, during a typical product lifecycle, patterns that were developed in 3D are re-engineered in the handover to production, or 3D visualisations are altered without the results being reflected in their associated patterns, tech packs, or bill of materials, and manual reconciliation and data re-entry consistently take the place of workflow management and automation.

Fashion garments are simply not – at least today – natively built in 3D in a way that allows the resulting asset to serve the same spectrum of use cases as 3D assets do elsewhere. Instead, fashion has coalesced around the idea of bi-directionally linking 2D patterns and digital materials to 3D visualisations of those elements that different actors progressively re-engineer or fork for their own purposes, but the apparel industry has struggled to merge those different things into a single cohesive entity.

This is why, at industry events and in quiet conversations between brands, you’ll often hear a distinction being made between digital product creation and a “digital twin”. In those discussions, DPC is rightly celebrated as a success story, but at the same time there is a lingering sense that it represents just a part of the puzzle, and that a full and complete digital twin, that can stand in for every possible use case, is the longer-term strategic vision – even for organisations that are considered advanced in their digital capabilities today.

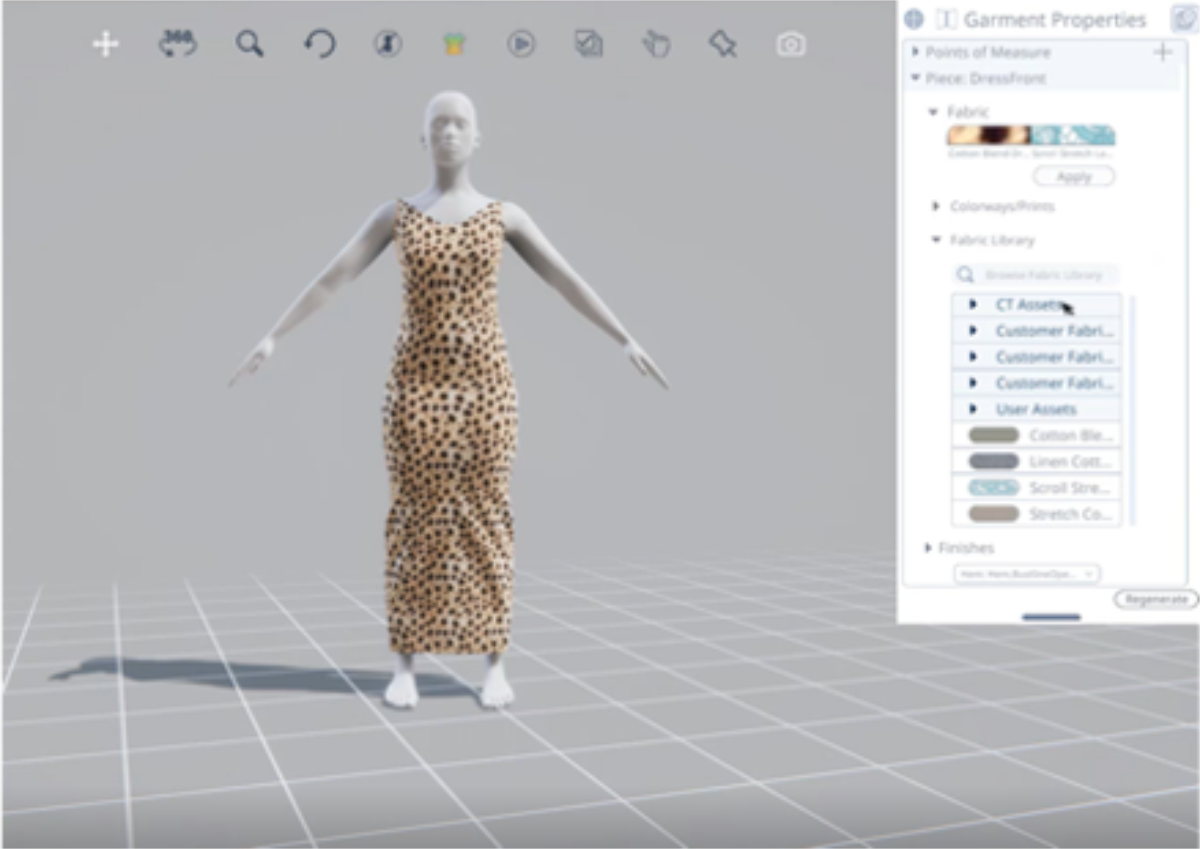

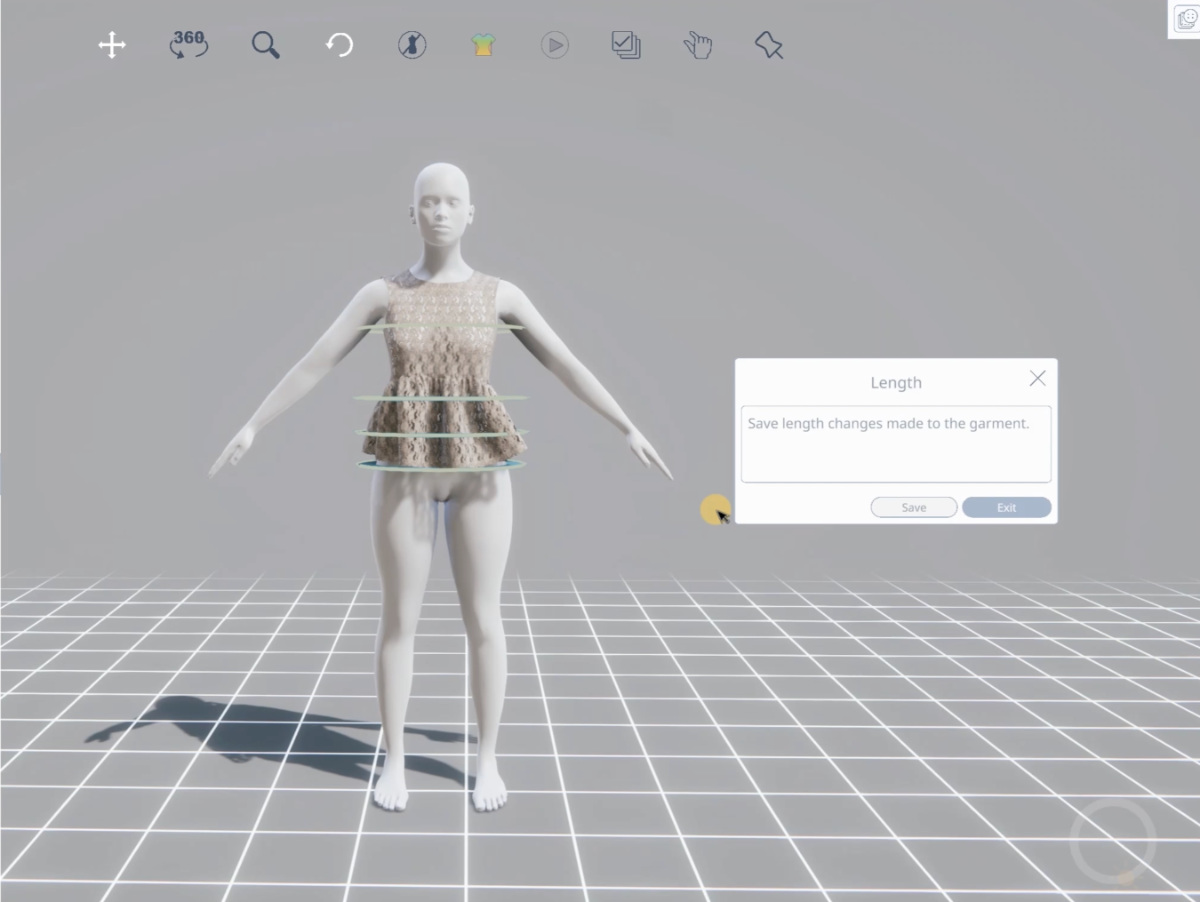

According to Clothing Tech, (whose new Fashionr solution has been conceived as a fully native “4D Clothing Creator” specifically designed around the idea of a complete digital twin, and is designed to allow brands to reclaim lost time and fundamentally overhaul their calendars) this separation between 3D / DPC and a digital twin is where the root of the problem lies.

By settling for optimising existing processes rather than challenging them, and by improving instead of overhauling the way apparel is created, the wider fashion technology sector has framed – and has continued to treat – DPC and digital twins as separate initiatives when they should logically be seen as one and the same.

Clothing Tech’s objective may be to challenge existing 3D and DPC strategies, but it isn’t to discard their value. From a sustainability perspective, for in-house collaboration, and as a way to reduce unnecessary sampling, shifting from 2D to 3D has provided some clear benefits for apparel brands. And within many of those organisations, DPC and 3D teams – and the creative communities they empower – are at the vanguard of business transformation, not just realising new ideas, but creating digital assets that add real value to their counterparts in sales and marketing.

But Clothing Tech sees a larger ambition, with the value already realised by DPC strategies as the springboard for a more fundamental, foundational transformation of clothing creation – one that’s rooted in a realistic way to reclaim lost time.

For context: the typical product lifecycle in apparel today is measured in double-digit months, and is made up of a linear set of processes which need to take place one after the other. Planning flows into creative design, which flows into technical design, which flows into material development and supplier management, which in turn cascades into sampling, approvals and onwards.

Unlike other sectors, where different processes, components, and pieces are all running in parallel, so that aggregate progress is being made at the whole-product or whole-collection level, fashion has largely kept to a siloed, sequential structure with manual hand-offs between each stage – meaning that technical design cannot begin until creative design is complete, and sampling can’t take place until both of those processes are completed.

And because each of these stages has its own built-in time requirement, each serialised process also contributes to the overall length of the go-to-market calendar. As a result, automation remains the exception rather than the rule, and the handovers between those stages rely on interpretation and reconciliation. Which means that digitising one sequential process, the way that current DPC strategies have, will not automatically digitise the one that follows – placing a hard limit on how much time can actually be saved in the overall product design and development calendar.

This is what Clothing Tech aims to address with Fashionr. The “4D” in the title refers to the emphasis that the team places on the fourth dimension of time – dramatically shortening the distance from initial design to finished product by fundamentally changing the workflow from a linear to a parallel structure.

Clothing Tech believes that this represents the full potential of digital product creation, and dispels the false distinction between it and the idea of a digital twin. By making a 3D asset the common foundation of every process and very now-concurrent lifecycle stage, Clothing Tech aims to make it feasible for creative and commercial teams to progress from an idea to a physical sample in days.

This same foundation should also ensure continuity and consistency between those different, simultaneous processes – with changes made to technical specifications being automatically reflected in 3D visualisations, and materials swapped out or recoloured in 3D being automatically updated in a tech pack and in costing calculations. Unlike today, where these are independent elements that must be manually linked and that do not consistently and accurate influence one another, Fashionr’s approach is to simply embed them all in a single, shared 3D asset that exists from the earliest stage of the product’s lifespan to the latest.

And when we look more broadly, Clothing Tech’s approach could also provide a more suitable foundation for the ambitions that fashion brands have for expanding the value of digital assets into new possibility spaces up and downstream. These might be general, such as sustainability, advanced costing, and virtual photography, or specific to Fashionr, such as automated draping, sewing, and tech pack production, and AI-assisted patternmaking.

3D, then, may not be new to fashion. But for all the progress the industry has made, there are still fundamental questions to ask – and answer – about why 3D and DPC have not, so far, altered the way apparel products are conceived and created.

Because every sector under the fashion umbrella now finds itself at a difficult juncture, where the demand and the expectation for 3D is setting a progressively higher bar – with everything from the carbon footprint of a collection to the way consumers experience it being targeted as a new way that digital product creation and 3D assets can deliver enhanced value. And this is placing greater weight on a foundation that has underpinned many individual improvements, but that has largely left the shape, scope, and speed of product creation untouched.

For many brands, this could prove to be a critical opportunity to re-examine the initial promise of digital product creation – not with the objective of replacing one 3D tool with another, but with an open mind to challenge and reinvent the entire process. Because it seems increasingly likely that a fundamentally different approach to DPC will be needed if fashion is going to truly shorten the distance between idea and reality to an extent that really earns the label of being the next stage of clothing creation.

About our partner: Clothing Tech’s ground-breaking Fashionr platform for 3D CAD empowers fashion designers to effortlessly merge creativity, innovation, and automation, infusing fresh vitality into the business of fashion and providing tangible, scalable assets needed to go beyond visual rendering.