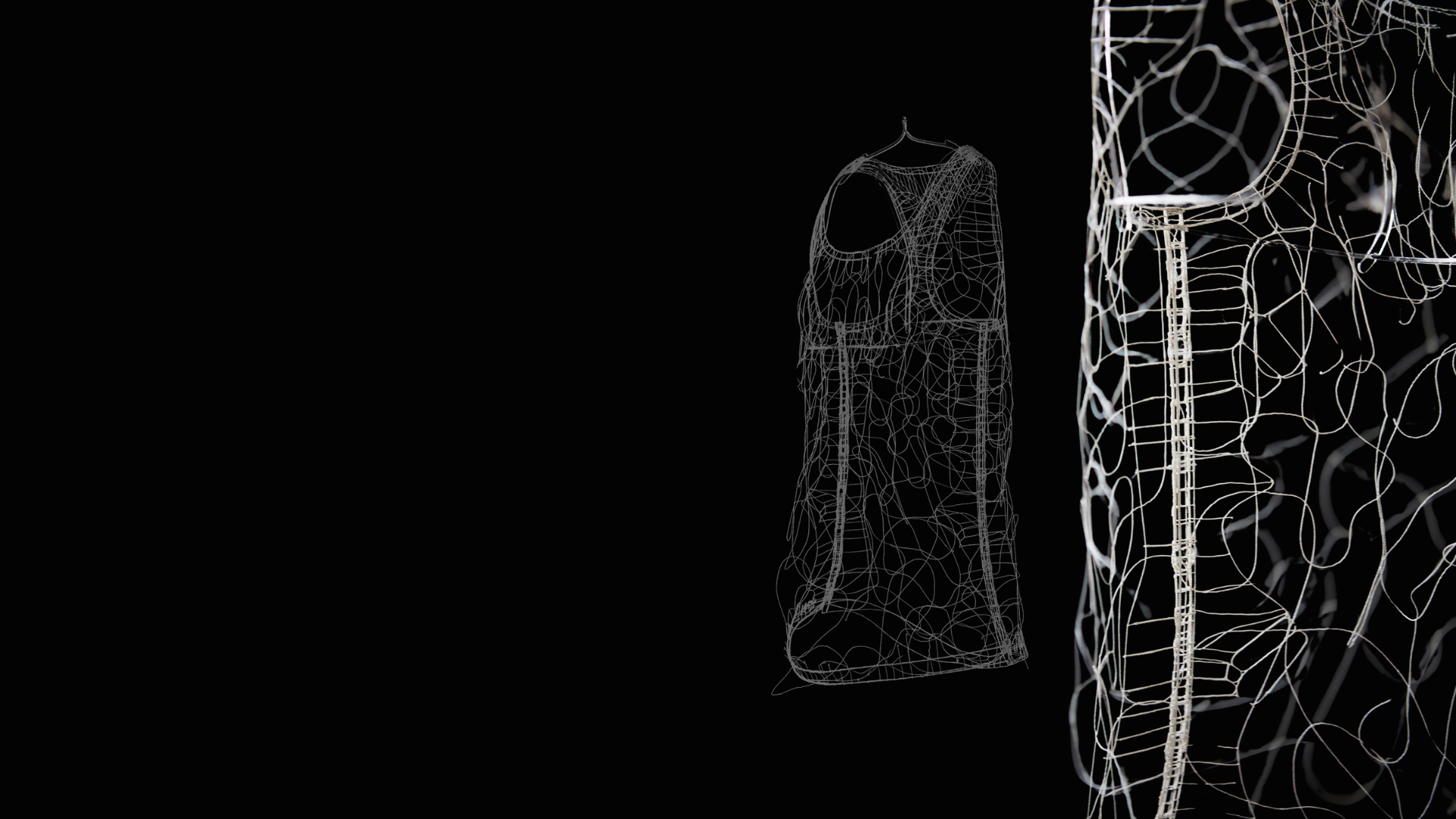

[Featured image credit: Erik Lindvall]

Key Takeaways:

- Addressing Fashion’s Dual Nature: Fashion serves as both a cultural force and a major source of waste and resource consumption.

- The Potential for Sustainable Innovation: Compostable clothing offers a way to address overconsumption while maintaining fashion’s artistic and cultural impact.

- A Vision for the Future of Fashion: A shift towards biodegradable materials can help reconcile the industry’s need for creativity with sustainability goals.

Editor’s introduction:

There’s a tension at the heart of the sustainability conversation: between fashion as a cultural force, a beacon, and a vital outlet for individual and collective artistic and social expression… and fashion as an outsize waste-generator and resource-consumer.

That tension has become especially evident in the last decade or so, since those two variables have grown more connected to one another. At the same time that fashion has increasingly come to define its success by expansion, volume, and an upward economic trajectory, the pace of culture has become progressively faster and more frenzied.

These are two entrenched arguments keeping the flywheel at the heart of fashion running. To be relevant in an ever-shifting culture, fashion must be faster to react, and smart about when and where it is proactive. To meet the demands of financial backers, fashion has to keep making and shifting more product.

For a while at least, this was a fairly symbiotic relationship. Fashion thrived on newness and speed both creatively and commercially. Both art and industry were headed in the same direction. But over time, as Erik Lindvall argues in this op-ed, the throughput of industry has become a burden on art; so much fashion is being created, and so much is being thrown away, that something essential is being lost in the deluge.

And now, in an era of overdue sustainability legislation, there is the very real threat that regulation of the industry’s unwieldy scale could end up involuntarily restricting its creative output.

One potential solution to this would be for the industry to voluntarily contract, creating fewer new styles and slashing production volumes in a somewhat-coordinated ‘degrowth’ strategy. But as previous op-ed writers have pointed out, very few industries will willingly reverse a financially successful course however short-term its runway might be, and from a consumer perspective it will be difficult to walk back from a time of creative abundance to one of austerity.

Across the aisle, people have grown so accustomed to being able to make what they want, and buy what they want, that even the looming reality of runaway climate change has not convinced either side to reverse course.

In recognition of all this, what if fashion started to take an “ashes to ashes” approach to creation – making clothing designed to biodegrade or be completely disassembled? Different from the refrain of “cradle to cradle,” Erik proposes a vision for the use of novel materials and manufacturing and recycling innovation to maintain fashion’s vitality as well as meeting its sustainability targets – an argument for invention as a way to protect and revitalise the art of fashion, not just as a tool for safeguarding the industry.

The concept of Fashion will never be boring, as life itself will never be boring. Society will also never be boring, and I can safely argue that it is less boring while I am writing this as it has ever been in the history of humankind.

credit: Erik Lindvall

Fashion has long enough now been held back by industry needs, by rational calculations made by engineers, economics and bureaucrats and by compliance demands that direct what fashion is.

It is time for us to break the cage of calculated rationality and disengage Fashion from the tiresome expectations of showing society as it is, to lose the chains of efficiency demands that encage it in the name of compliance, material sourcing, supply chain discussions and business fairs.

Do not misunderstand me – these are essential components to implement if we are to create a circular and most necessary society (and survive) – but these are not essential components of fashion. They are part of the Fashion industry.

Fashion is the natural space for individuals or groups to express individuality, inclusion, exclusion, political ideas, ideologies and lifestyle, but it has also been the best place for visualising the changing of the tide.

The concept of Fashion – not to be confused with the industry of fashion – has historically been the world where the zeitgeist of time has been manifested alongside the foreboding of societies to come.

credit: Erik Lindvall

I explicitly separate the phenomena of fashion from the industry of fashion, since they are different concepts, although somewhat vague.

This is something that professionals, academia and laymen who are active in the sphere of Fashion often miss, or mix up intentionally, the concepts being vague and all.

Another somewhat vague concept is the commonly used value word quality.

Everybody wants it, especially now when we want to abandon the wear-and-tear business models and keep our products longer.

When we demand quality, we take the meaning for granted. Quality is a value word that nobody really challenges. Everybody wants “quality” because it implies that value is being created.

But “quality” is a vague concept, almost always alluding to the essential question that needs to be asked; yes, value is created – but value for whom?

The material has a limited life expectancy but is instead packed with bio functions such as cooling and potential to carry components that can be absorbed through the skin.

credit: Erik Lindvall

I wrote the below article in FORM magazine 2014 under the title “Ashes to ashes” where I argued for a circular society based on radically different expectations of quality, but also a society where consumption and time were fundamental components.

Instead of owning our stuff, we could experience them. Think of it like how the forest works; it is based on a consumption of “products” that grow, live and die. When you think about it, nothing in the cosmos is detached from the time and space dimensions except from the singularity of black holes. So why should we believe that our stuff differs?

The article below was written ten years ago, but it could have been written today. Up until now, we have engaged in reforms, but no real change. There are desperate times ahead, and it is maybe time to visualise society as it should be, not merely as it is.

The article challenges the human centred perspective of defining “quality” as value for man with the argument that we – to truly become circular – need to redefine the vague concept of “quality”.

We need to include the biosphere with all sentient beings, biodiversity as well as coming generations in the recipients of the values created by mankind. Then we will have the only quality – as in value for all stakeholders – that matters over time.

credit: Erik Lindvall

Original article: Ashes to Ashes

Could clothes that deteriorate turn the problem of overconsumption and at the same time raise existential questions?

“The new world hunger will never leave you,” sang Joakim Thåström and the Swedish postpunk band Imperiet in the 1980s. Perhaps it is time to accept this hunger as something more than human, and instead of denying it, curse it and, after half a century of stigmatising, embrace it?

Most of the environmental impact of our clothes today takes place after manufacture. We are researching textile materials that are made from 100% compostable materials like cellulose and milk proteins. Innovative materials that have the same characteristics and flexibility as cotton or silk.

The fashion and textile industry is constantly looking for materials that last long and with a lifespan comparable to cotton, but what would happen if we took the opposite approach?

game skins and digital fashion can be seamlessly brought out from the virtual world, into the physical.

left credit: Rita Roslin/Guringo Designstudio.

If we produced garments that are wearable for only a short time, and then returned to the cycle? These fleeting clothes, these flowers of the day, will soon be fully possible to produce, and the manufacturing process would be much cheaper than knitting threads.

Garments that age could also raise the issue of a society that is not based on the same consumption patterns that we see today. The textiles look the same as what we are used to, but just for a shorter time, before they decompose.

By investing in perishable consumer goods with short lifespans, there are now opportunities to create a fashion world in which fast fashion and wear-and-tear goes from being regarded as the industry’s weakness to being something positive for both consumers, businesses, and the environment.

Clothes that are like good food. They cannot be owned, but rather experienced, and they can show us a renewable world based on transience instead of the all too prevalent notion that things should be produced to last. In a society where the future is anything but bright, it is also time to bring fashion out of the museums, to where it is all too often dismissed, and show a possible future in which social issues and fashion aesthetics can meet again.

credit: Erik Lindvall

The great advantage with compostable clothes is not only that they are much cheaper to manufacture, but also that they intuitively embrace the progressiveness and consumption habits that the fashion industry is largely based on. Glancing at the value chain of a garment, and its possibilities of being manufactured on site and on demand, the economic opportunities are astonishing. Materials that need not last long may perhaps not require long transports or marking down.

In his book Yes is More from 2009, the architect Bjarke Ingels suggests that we must leave the neo-Protestant notion that sustainability must hurt, be dull, and that we have to stop doing all that we enjoy. We should embrace all aspects of being human, and find alternatives to keep doing what we like, but in other ways. In this way, we create a better society without a constantly bad conscience.

credit: Erik Lindvall

So, will we soon be able to consume as much as we want, while keeping a more playful and carefree approach to how we dress? Perhaps as consumers, we can finally buy the extravagant clothes that we may only want to wear once or twice and then never again, without a guilty conscience. Clothes that, like windflowers in spring, also remind us of our own impermanence.

Here, the vision may be just that, only a vision. But it does go a long way. We must dare to look ahead and question and re-evaluate the actual premises of our society and its systems without condemning, limiting or even comparing it with old habitual behaviours. The renewable society demands that we stop changing trends and instead start changing structures.

We cannot keep running in place, longingly looking over our shoulder. We need visions, both in fashion and in society.