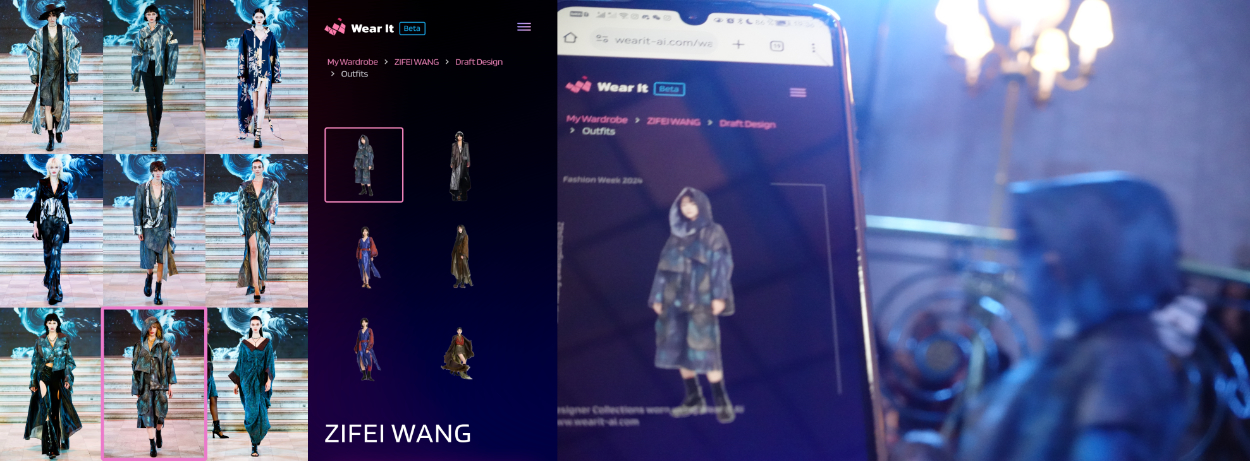

[Featured image: Wear It x ZIFEI WANG SS25 London Fashion Week runway]

Key Takeaways:

- Virtual Try-On Hasn’t Been Widely Adopted: Despite its promise, virtual try-on technology has not been integrated into mainstream online retail. Its limitations in providing a tactile experience and accurately replicating the in-store try-on have hindered adoption.

- Realism in Virtual Try-On Can Reduce Sales: While AI-driven realism in try-on can help consumers visualize outfits more accurately, it can lead to fewer impulse purchases, as the “benefit of the doubt” is removed from the buying process.

- Social Media Over Online Retail: Platforms like Instagram and TikTok have become primary destinations for fashion discovery, with many users prioritizing visual engagement over actual ownership of clothing items. Virtual try-on could become part of this ecosystem, allowing consumers to try and share their looks without needing to buy physical products.

- Virtual Try-Ons as Content: Virtual try-ons serve as a form of content that engages consumers and drives social commerce. Consumers enjoy the experience of trying clothes without the need to purchase them, leading to a shift where content consumption becomes a key form of engagement in fashion.

Fashion eCommerce returns have become a huge cost sink and a significant environmental burden, with billions of dollars in unsold or returned goods ending up in landfills each year. This is a result of consumers not being able to fully gauge how items will look and fit until they physically try them on. Naturally, one would assume that the solution lies in improving virtual try-on technology to give consumers greater confidence before purchasing. Virtual try-on has long been positioned as the next major disruption for online retail, yet it remains notably absent from most major eCommerce platforms. Over the years, various solutions based on 3D simulations, augmented reality, or 2D representations have been rolled out, yet none of them have truly taken off in the way that many proponents initially expected.

There are several reasons for this lukewarm adoption. First, while virtual try-on offers novelty, it doesn’t resolve some of the biggest friction points of online shopping. Tools that provide a visual approximation of how an item might look are often clunky, difficult to navigate, and not integrated seamlessly into the shopping experience. Tools that collect consumer measurements and create fitting avatars have merits for size recommendation, but fitting technologies still aren’t scalable. The variations in body shapes, movements, and preferences make it extremely challenging to design a one-size-fits-all virtual fitting solution. Brands and retailers need to have 3D simulations or many types of product assets in specific formats compatible with the specific try-on method in order to make try-on possible for their products one by one.

The economic reason is another friction. Retailers are faced with the challenge of balancing customer satisfaction with cost efficiency. Offering free returns has become a standard practice, not because it’s ideal, but because it works better for the bottom line. It’s often cheaper for retailers to offer free returns and dispose of unsold or returned items than to invest in complex technologies like virtual try-on systems. After all, most of these technologies still don’t fully solve the problems of fit, comfort, and tactile experience. For many consumers, seeing a static 2D/3D model or AR projection on their screen doesn’t replicate the tactile experience they value when trying on clothes physically. While returning clothes may be a minor inconvenience, the primary factor that drives consumer behavior is money. If clothes are inexpensive, there’s little to no hesitation to buy, try, and discard. When the stakes are low, returns aren’t viewed as problematic but rather an expected part of the shopping process. Retailers, by offering free returns, reinforce this behavior, creating a cycle of overproduction, excess, and waste, all of which are detrimental to the environment.

Putting technology and economic hurdles aside, let’s also consider the incentives of adopting virtual try-ons for the retailers. Sellers of virtual try-on technologies may believe they can help retailers reduce returns. But on the other end of the value chain, they must convince consumers. If visual virtual try-ons become hyper-realistic and fitting virtual try-ons 100% accurate, not only may returns reduce, impulse purchases should also reduce. Once a consumer sees exactly how an item looks and fits on them, the excitement or aspirational fantasy of the purchase is replaced with reality, which may lead them to reconsider the need for that item altogether. The overall revenue of retailers would reduce. Is this what retailers want? This is a fundamental tension between providing a “service” and driving sales.

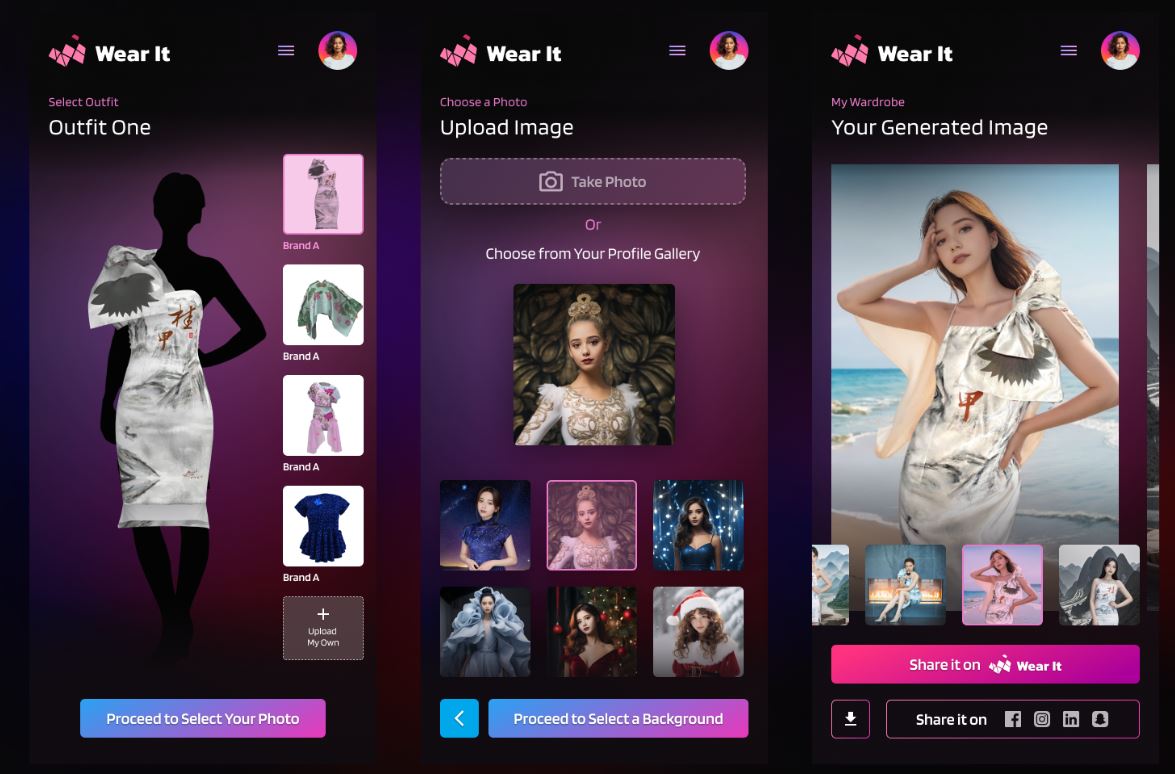

That is not to say virtual try-on has hit a dead end. There’s a silver lining. If virtual try-on could bring such an effect as reducing retail revenue at an industrial level, it can fundamentally disrupt the retail model. Consider instead of retailers enabling virtual try-ons on their websites, virtual try-on technology becomes available for all consumers in a platform-agnostic way. Anyone can self-define any clothes they want to try on digitally, instantly, and accurately. This is now possible with a combination of generative artificial intelligence and computer vision technologies. This satisfies consumers, helping them make purchase decisions before committing to buying or ordering excess just to try. Again, retailers will take a revenue hit as a result, and they will be forced to adapt to innovation and focus on ways that increase profit margin without relying on selling more. For example, brands can produce less with a better understanding of what to produce. This can positively also reduce the overproduction, waste, and pollution problems the fashion industry is famous for.

A further factor is the shift in consumer behavior, particularly among younger generations. Many students and young adults have expressed more interest in sustainability and second-hand fashion. They are often not interested in buying new clothes at all. They view fashion as an experimental playground, and they are more inclined to swap, borrow, or buy second-hand pieces than to engage in the consumption cycles encouraged by traditional retail. The narrative that fashion needs to continuously pump out new clothes to remain relevant is increasingly being challenged.

In many cases, what people are truly after isn’t even ownership of the clothes. Social media has transformed the way people engage with fashion, with many users seeking out outfits for a one-time visual experience—whether for a post, event, or photo shoot—without the need for physical ownership. Consumers want the experience of “wearing” the fashion without the financial or environmental cost of actual physical goods. Virtual try-on can tap into this evolving consumer mindset.

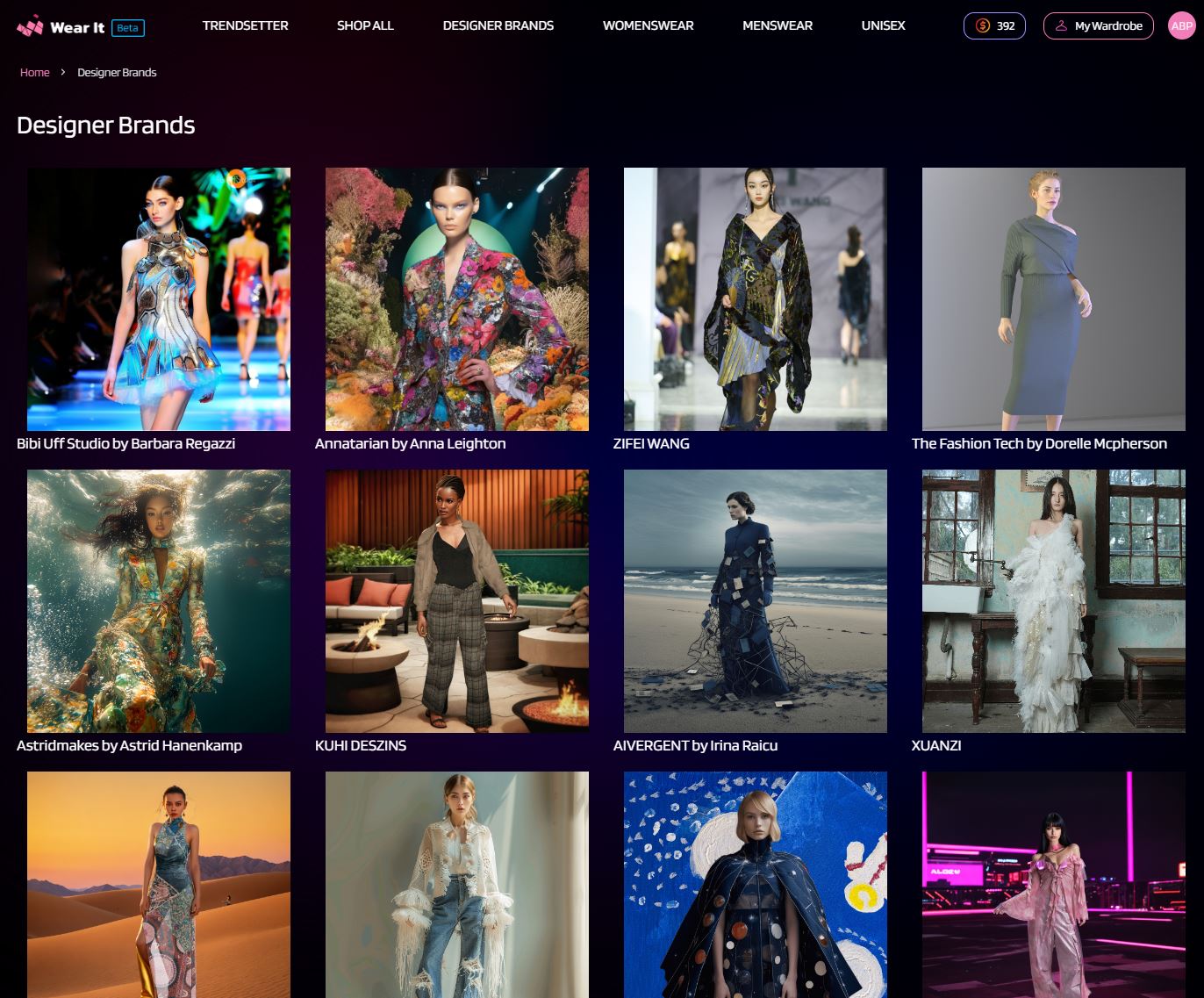

Consumers are no longer primarily using eCommerce platforms as their main point of fashion purchase. Instead, user-generated content is now at the forefront of selling fashion (social commerce), as consumers are increasingly relying on social media platforms like Instagram, TikTok, and YouTube to discover, explore, and share styles. Influencers and everyday users curate looks and outfits in ways that resonate deeply with their specific communities. Consumers trust and connect with influencers and their peers more than with glossy, impersonal product images on retail sites.

This shift towards social commerce means that virtual try-on technology, previously thought of as a tool for traditional eCommerce, now has to evolve and become part of this new landscape. It isn’t just a tool for simulating how a piece of clothing looks or fits on a person—it becomes the content itself and can drive consumer interest, engagement, and sales. With the rise of AI-generated content of hyper-realistic visuals of consumers in different outfits, virtual try-ons fuel the social commerce engine. When a consumer tries on an outfit virtually, they are satisfying their own curiosity but also creating shareable content that generates visibility for the brand. The imagery produced by these try-ons serves as authentic, user-driven advertising and community-led marketing.

This also means fashion brands no longer need to rely solely on physical products to engage their audience or make sales. They can start selling AI-generated content—allowing consumers to experience new styles and outfits visually before any physical product is even made. This is a game-changer for fashion, particularly when it comes to production efficiency and sustainability. By creating demand first through social commerce, brands can move to an on-demand model where products are only physically produced after they are sold, with accurate quantities.

However, for this system to work efficiently, supply chains must become highly agile. In regions like China, this agility has already been achieved. The country’s labor-intensive and mature manufacturing infrastructure allows for rapid production, meeting fast-evolving demand driven by micro-cultures, trends, and communities on social media. For Western markets, which traditionally rely on longer lead times and offshore overproduction, this presents a significant challenge. To catch up, the West needs to invest in automation technologies, AI, and on-demand systems that can enable faster and more flexible manufacturing. This would allow fashion brands to respond in real-time to demand created through social commerce. The key to the future of fashion will be a combination of digital-first experiences, powered by AI, and agile production systems that respond to fast-moving consumer demand driven by subcultures and online communities.

Ultimately, fashion consumers are not always purchasing physical goods—they are engaging in creative, visual consumption. The job-to-be-done isn’t necessarily to buy clothes but to experiment, window shop, and immerse themselves in fashion experiences. Through democratized virtual try-ons, consumers can try on any outfit they wish, share their experiences, and engage in social commerce—without needing to purchase or own the physical garment. This creates a sustainable cycle where content serves as the consumption, and production follows only when necessary. Instead of pushing consumers to buy more, or educating consumers to buy sustainably, when trying on clothes becomes the experience rather than serving the purpose of purchasing, supply can meet true demand.