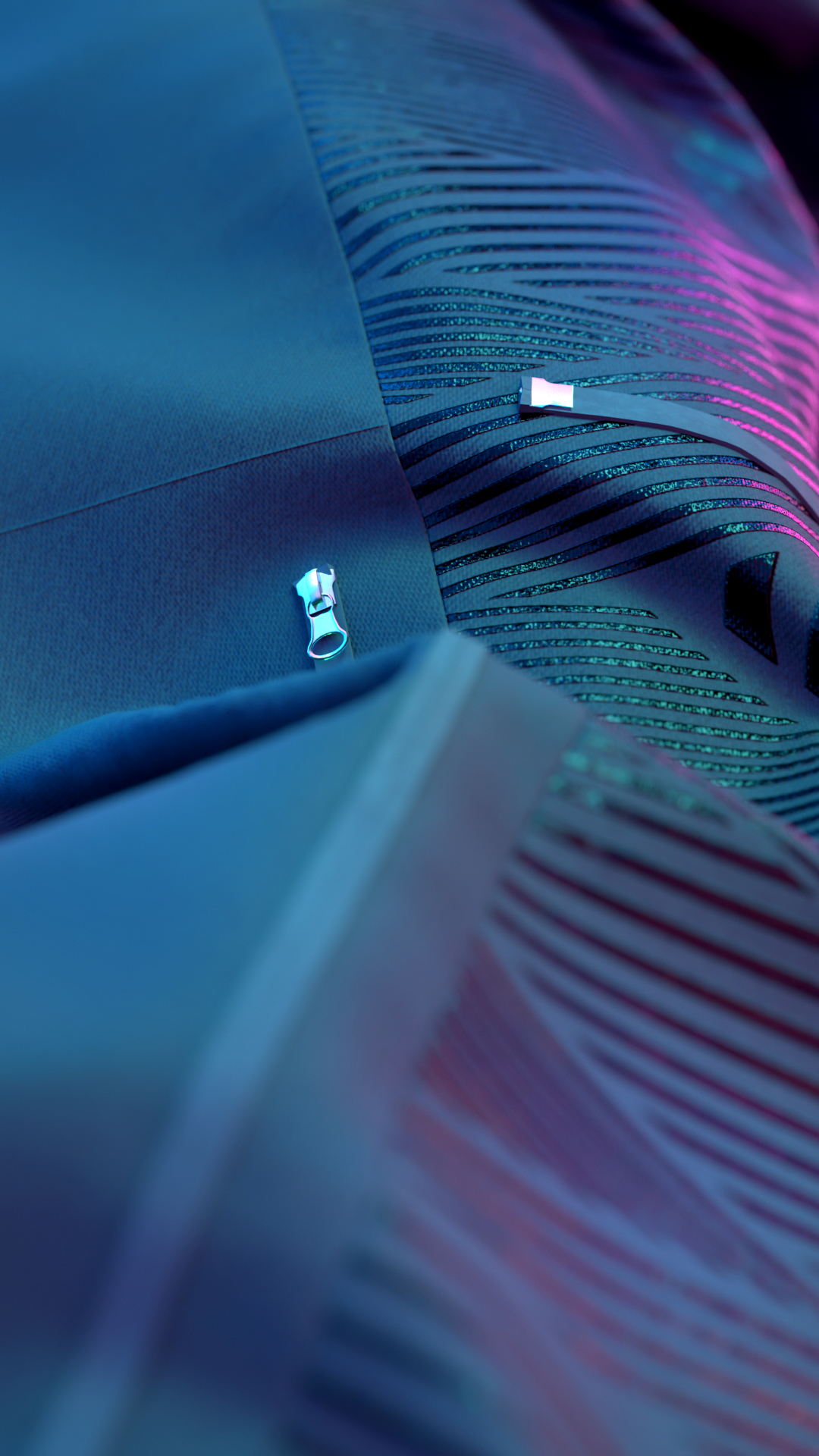

[Featured image: Decathlon]

Different types of products have different challenges and different considerations when it comes to working in 3D. How has a business that covers many, many different categories – all with unique performance demands – approached the strategic, technical, and cultural sides of digital product creation? And what have been some of their key findings from testing the frontiers of possibility in DPC?

To find out, The Interline sat down with Cyrille Ancely- Component Digital Twin Leader at Decathlon – and Frederic Frache, Modelling And Texture Artist for Decathlon’s Product Asset Team.

Trained as a transportation and industrial designer (with experience working for automotive giants like Renault, Stellantis, and Lexus) Cyrille began working with Decathlon as a freelancer, before being invited by the group’s Head of Design to join the team and co-write the ‘digital chain’. Today, Cyrille is a key member of the team facilitating the global sports retailer’s multi-year transition into 3D, and he has recently also been working with the CGI team to develop new strategies for the company.

Frederic has a similar background in product design and 3D modelling, working for both automotive giants and in the creation of CGI for architecture. He initially joined Decathlon as a footwear 3D modeller, before joining Cyrille’s team to work on material digitisation.

The Interline: Working for a company that covers so many different product categories – everything from yoga mats and exercise bands, to technical running apparel, camping equipment, and performance footwear – how have you approached the challenge of building 3D pipelines? Has the philosophy been to build specific workflows for each type of product, or to try and codify a standard that works across all of them?

Cyrille & Frederic: When we started the project in 2019, the first phase was to get an overview of what was already accomplished within the company. Decathlon was, at the time, made up of many independent brands (85 brands) and about nearly 30 different specialised industrial processes within them, covering categories as different as helmets, optics, lighting and many more.

Some of those brands and processes were already incorporating 3D, and they had begun to build their own pipelines. So in February 2020 we hosted an internal event to showcase what had already been achieved – and we also invited some external companies to participate, including luxury fashion brands, automotive giants, and technology companies like Substance, which had just been acquired by Adobe.

Then Covid happened.

It might be weird to say, but the pandemic was really helpful from a DPC perspective because it served to push this topic to the top of our priority list. And what emerged out of that global emergency was a drive at Decathlon to create a seamless workflow that would push the design process forward – covering the full cycle from first sketches to production and marketing.

We defined four main product areas and started to build pipelines based on existing knowledge: apparel and footwear were the own categories, then we had a dedicated category for soft equipment which mainly focused on bags but also included tents, and then another area for hard equipment, which focused mainly on bikes.

Our purpose was (and still is) to set those pipelines at a company level. This has been the key to creating and standardising workflows, upskilling our teams, developing digital tools when we needed to, and standing-up services internally.

Diving deeper in each product category, we have found it necessary to establish some more granular workflows (tents, seamless products, golf clubs and other narrow categories needed this) but we always start from that top-level global segmentation.

The Interline: What’s your perspective on how the user community for digital product creation has evolved? Do you see 3D and DPC primarily serving design and development roles, or are these initiatives delivering value to other personas in merchandising, sourcing, marketing etc.?

Cyrille & Frederic: We first focused on the Design community, because our driving principle is that every step in 3D should be towards the creation of an ideal, “dreamed” seamless workflow that will allow us to create digital twins at the start, that then serve every requirement along the entire value chain.

Quite quickly, though, we realised we had to also focus on the marketing part, which is the visible part of the 3D iceberg.

We also use CGI content to give the entire company visibility into what our strategic goals with DPC are, to demonstrate what’s possible, and to align everyone on the vision for why we need digital twins of not just our finished products but also our components – materials, accessories, spare parts and so on.

The merchandising process is also an interesting topic, because 3D gives our visual merchandisers the ability to visualise what their stores and shelves will look like, without needing to mock them up with real products.They can also work on tomorrow’s in-store experiences, such as allowing customers to visit a tent in VR when stores do not have enough space to install the whole range.

Using 3D also allows us to work from the first design stage towards product repairability, including some interesting work around how we can repair products using 3D printing.

From a component point of view, especially in textiles, 3D also allows our teams to test new fabrics without having the physical swatches, or even asking for our supplier to produce anything if we are not at least 80% certain we will use it. This, for us, is a huge step in sustainability, so DPC is also extending all the way to that community and that strategic mission.

The Interline: One of the keys to extending the DPC community – and realising extra value from digital assets – is going to be building trust in the knowledge that a digital asset, whether it’s a material, a trim, or a complete finished product, is a one-to-one representation of the physical asset. Where have you seen that trust working well?

Cyrille & Frederic: That trust-building is indeed one of our main problems. As we want to remove some physical prototypes, but not all of them, we still need to validate physically what we will sell to our customers, because we are, after all, selling physical products.

In terms of where trust is effectively being built, from a visual perspective, our stylists and designers seem really confident in the ability to visualise products in 3D before even producing a single prototype. We still have some minor issues with building trust in colour selection, but it is more a matter of best practice than any concrete limitation – and I’m sure everyone reading this report understands that even in real life colour perception is a huge and complex topic.

Colour blindness remains a fairly common disorder (it affects around 8% of men and 0.5% of women, moreover it seems that men and women don’t see colours exactly the same way to begin with) and on top of that lots of people visualise colour – and make colour-related decisions – on non-calibrated screens. So our challenge there has been providing training to point out why issues arise, and to help correct them with a set of best practices.

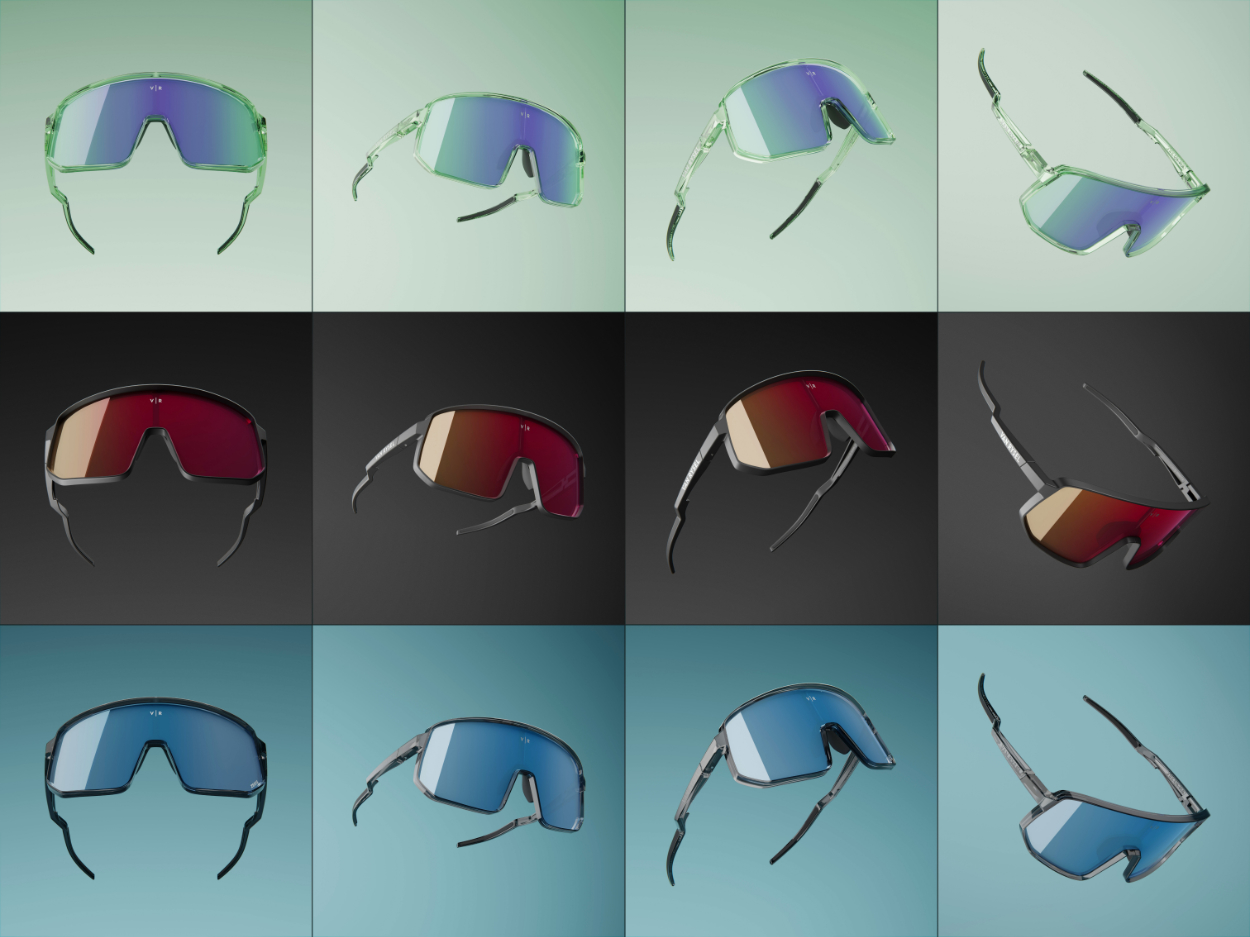

Our marketing teams are also completely into it, especially in footwear and hard products, since we can automate packshot creation and build a consistent set of contents for all our different products before even receiving a physical product. This has been a game-changer for them.

The Interline: Conversely, where do you believe it’s currently more difficult to establish trust in digital assets?

Cyrille & Frederic: For some other communities such as pattern makers and prototypists, the ability to simulate product behaviour early in the design process is vital. So when we talk about products where each project starts with a soft material, such as apparel or even a tent, we’re dealing with a different set of demands and expectations

At Decathlon, we are focused on performance products, which cater to everyone from beginner to expert. Implicit in that is the understanding that we need to use a lot of technical fabrics that are complex and difficult to simulate, for a wide range of different purposes.

The main apparel 3D software is built around simulating “prêt à porter”, which means its tools and algorithms are aimed at representing basic structured fabrics.

That gap is, today, one of the main problems we are facing. Because for the teams we have working on performance-oriented apparel,, if we are not able to properly simulate a product’s behaviour to the extent that they can trust it enough to sign off on the type of products they need to create, why should they even use 3D workflows?

Even with the gains that we’re seeing elsewhere in digital product creation, it’s important to recognise that the 3D workflow does increase the amount of daily tasks our users need to perform – especially if the physical step is still necessary.If that’s the case, then we’re arriving at the same result via a route that introduced more friction. This is the kind of concern that can lead to pushback against the 3D process, and it definitely works against the idea of building trust.

The Interline: There has been a significant push towards “digital twins,” or digital representations of products that can stand in for every use case where a physical example would normally be required. Which product categories do you believe are currently the closest to having that vision be viable? And which are maybe the furthest away? This seems to be very much a question of trust at its heart.

Cyrille & Frederic: To be honest, I don’t think we will have a single digital twin that will be able to cover all the use cases or needs we have. At some point, we will need to convert it to another file for a specific purpose (simulation, VR, animations) But having a 3D file that evolves through the product design process, helps to have the most accurate reference at every step.

There is a technology gap also. In the design of hard products, files are created for production that use surface or volumetric 3D modeling, while rendering and animation 3D technologies are based on polygons. So at some point of the process, we will have to convert one format into another.

This is where the accuracy and the standardisation of the model is so important, because it dictates how easy or difficult that process of converting from one use case to another will be. So we have to define what each role needs to be provided with in order to move forward, and we need to settle on standard modelling procedures.

Textile / Apparel categories actually have a bit of an advantage here, since 3D apparel design software uses the same kind of geometry that CGI imagery is using, which makes it potentially one of the most promising pipelines.But here again, it depends on the end use, and there is a lot more to take into account than just geometry when it comes to building complete trust in 3D in apparel..

We also have some more unique processes and products, such as tents or welding, which are so individual that there is no specific software developed for them. Those are the areas where we work on crossover processes, or where we develop internal plugins to allow us to move forward.

The Interline: When it comes to simulating different elements of products, from fit to performance, it feels as though there is perhaps a gulf between the demands of ready-to-wear fashion and other categories – especially outdoor and performance gear. Is this something you’re encountering?

Cyrille & Frederic: As I mentioned earlier, there are some difficulties when it comes to simulation on the apparel side- especially because we are working on products that use technical fabrics. By their nature, some products are very tightly-fitted, which makes it even more difficult to have a workable simulation of those.

We also work with seamless products which are constrained on the body, with different compression zones. And we create equipment, like tents, where we want to be able to simulate how the materials and the construction will behave in specific conditions like wind and rain, but as far as we know there’s no software out there that currently answers to those specific demands.

The Interline: Do you believe that there is still some runway to go with current 3D design, simulation, and visualisation tools, or are brands now beginning to test the limits? In the case of the latter, how do you believe fashion companies and technology vendors can work together to expand those limits – and in what areas?

Cyrille & Frederic:We are at the beginning of a new area for digital design. For the past six years, lots of software companies have invested in the building or translating solutions and capabilities from other sectors into product-centric industries. Companies from video games, like Unity, Epic or Adobe (with Substance) clearly see a lot of potential in those fields.

I also see AI opening up new horizons that will help us transform our processes at a larger scale.

To be clear there are still lots of things to work on, especially in creating standardised protocols like mechanical measurement to simulate apparel consistently in different software and file formats – to give us a standard material that can be transferred. But if we want to accomplish that, then it will require technology companies, suppliers, and brands to work together.

The Interline: The other side of building trust in digital representations is on the consumer end, where it’s not just a case of reflecting the products accurately, but showcasing them on convincing-looking avatars. And where sportswear and performance wear is concerned, that also means showing them in motion. Where do you believe the industry is at on this journey?

Cyrille & Frederic: On the consumer end, we have nearly no technical limitations. We can showcase digital products, we are able to do face swapping, we can create realistic avatars and animations.

I think the bigger concern downstream is a cultural or sociological one. Across AI, 3D, and the combination of both we are now firmly on the edge of the uncanny valley – a theory coined by Japanese roboticist Masahiro Mori in 1970 which tells us that the closer something gets to looking human or realistic without being 100% there, the more it provokes a feeling of anxiety and unease. The effort required to pursue hyper-realism and get past that feeling is significant, and there is an ethical core to the discussion of how far we should be pursuing that goal.

Should we be promoting content featuring real humans, which I would describe as more authentic, or content that is very similar but generated by AI or via advanced 3D rendering, which saves money and production time? Which of those avenues will society ultimately value the most – especially from a sustainability point of view?

The Interline: Finally, how do you see AI and DPC interacting in the near future – whether that’s enhancing one another, or even prompting a re-evaluation of where the frontiers between the two are?

Cyrille & Frederic: AI is already present in our daily tools, the question is not if we need to use it, but how and where.

On the creative design side, those tools can help to quickly extract new ideas from creative minds. But humans need to be involved in the process, because AI is not able to think outside the box – meaning outside its training data – and at some point content will become less and less interesting if we have AI generating materials based on AI-generated data.

On the other hand, AI could give us the capability to more quickly generate some types of data, such as the mechanical properties of components, or enrich other types so that we can build fewer prototypes than before, meaning less production and less pollution.

The difficulty in the AI field, for me, is that there is a very thin frontier between beautifying a render and moving, consciously or unconsciously, away from reality – to the extent that sometimes a brand could end up over-indexing on a sub-optimal design and putting it into production. The goal of DPC, of course, is to reduce lead time and to increase the confidence in our design choices, and the use of AI cannot end up being adverse to that.