This article was originally published in The Interline’s DPC Report 2024. To read other opinion pieces, exclusive editorials, and detailed profiles and interviews with key vendors, download the full DPC Report 2024 completely free of charge and ungated.

Key Takeaways:

- DPC promises transformation, but many initiatives stumble. Unlocking real value requires more than just technology; it demands a deep understanding of the design workflow and a commitment to long-term change.

- Designers face a significant hurdle transitioning to 3D. It’s not just about learning new software; it’s a fundamental shift in how they think and create. Without the right support, adoption will falter.

- Ignoring design leadership can derail even the most ambitious DPC project. A leading brand’s experience proves that overlooking the creative process and the needs of design leaders can undermine the entire initiative.

- Effective DPC implementation hinges on tailored change management. Clear communication, targeted training, dedicated change agents, and a robust feedback loop are essential to ensure designers embrace—not resist—the digital future.

Fashion, an industry that is obsessed with the new, has been surprisingly slow to move to novel ways of working. Digital Product Creation (DPC), though, is heralded as an almost magic step-change in the way we design and develop our products. For an industry that can be so averse to advancing its processes, it’s important to remember that when it comes to DPC, the end of the journey is not a mirage.

In practice, though, everyone who has started on this path has discovered the expedition was tougher than promised. The primary impetus for digital transformation is usually the cost and time savings that will be realised, but actually unlocking them isn’t always a straight shot: success requires thoughtful long range plans, significant resource commitment, and steady leadership support. And shifting priorities can alter the map as it’s being traversed.

Are designers just “extra”, or is digital transformation just extra hard for designers?

Preparing for the transformation potential of DPC means acknowledging that different functions will require different amounts of effort and support along the way. It’s a whole-business journey in the longer term, but one that needs to be walked in shorter segments where varying sets of people are shouldering the heaviest burdens at different times.

For tech designers and fit technicians, garment patterns and how they form 3D shapes is intrinsic to their remit, so digital pattern manipulation is an extension of their daily work. Nonetheless, acquiring fluency in 3D tools still requires significant time and effort on their part; traditional technical skills do not automatically translate into technology skills. For merchandisers, seeing data in multiple arrays is equally familiar, but being able to visualise their line instantly from multiple perspectives requires a new visual tool and potentially a slightly different mindset.

For designers in particular, the learning curve can be very steep and arduous. The shift from 2D ways of working to 3D requires both a conceptual shift on their part and the time to acquire (or for newer graduates refresh) complex technical skills.

Drawing is generally designers’ rapid iteration tool of choice, but drawing in fashion is not the same discipline as drafting in engineering-focused industries. Hand sketches or vector drawings do not have the construction accuracy of 3D designs, and there has traditionally been a line (albeit a sometimes-blurry one) drawn between creative and technical designers.

Before a design can be created in 3D, designers need to have figured out which block to start with – a degree of precision they can postpone with 2D sketching. The aesthetic fit intent of a design might shift multiple times in the design development process: in 2D designing, the same sketch can merely be labelled differently (skinny fit to slim fit, say), while in 3D, each fit type is likely to require a new 3D style. That is to say, 3D designing requires designers to resolve many questions and a level of detail earlier than in 2D ways of working.

Additionally, for designers who are expected to design directly in 3D, they are asked to understand and manipulate patterns and virtually sew – muscles they might not have used since fashion school, if ever. These shifts in ways of working need to be accounted for in all DPC planning – and they lie at the root of many of the misaligned expectations we hear about between strategic DPC sponsors and end users.

Put Design Leaders’ Oxygen Masks on First

Design leaders are an additional consideration. These lighthouses provide the inspiration for the collection and communicate storytelling as it evolves through outfitting. All planning has to take those dual creative and managerial responsibilities into account from the very start of the DPC journey.

In my research for this story, a Senior Design Director at a leading European fashion brand told me how their corporate DPC initiatives faltered, in part, by overlooking this point. What started as a reasonable plan to reduce the number of physical samples for wholesale showrooms, ended up petering out because:

- The outfitting process is iterative and creative. This is how design leads communicate key fashion ideas to buyers and the final customer. Even in a world of unlimited physical samples, the outfits are fine-tuned and perfected. When physical sampling was reduced to just the planned key looks as part of their DPC initiative, the ability to “zhuzh” and replace one garment for another ended up having a detrimental impact on the wholesale business.

- Moreover, these top-of-the-pyramid fashion ideas did not always execute well in 3D. The magic of specific trend fabrics did not show up effectively digitally. When viewed scaled down on computer screens, key textures and artwork looked pixelated, which further undermined confidence and eroded people’s trust that what they saw in 3D was representative of reality. (Material digitisation and development is also its own under-recognised part of any successful DPC initiative!)

- To make matters worse, 3D sampling pipeline challenges meant essential styles sometimes were not even available in 3D. Nor were resources devoted to helping facilitate 3D outfitting.

In short, an essential creative function was kneecapped by insufficient DPC planning from the start, as well as technical and process limitations. And I’m sure almost everyone reading this report can imagine a similar set of circumstances playing out at other brands.

The key lesson: even if the challenge of resolving digital outfitting cannot be solved easily, it is imperative to address design leadership challenges and work to solve the problems they face with urgency.

Design-Specific DPC Change Management

As challenging as it is to implement and connect new technologies and streamline processes, convincing people is often the most difficult part of the journey. As changes are being implemented, communication is essential. The plan must be clearly and consistently communicated to all levels of the organisation who will be impacted, and context must be tailored to specific functions. The specific benefits for both design leads and team members need to be spelled out in language that resonates with them – not just in broad business strokes.

The strategies I’ve outlined here may seem like common sense, but they go deeper than traditional change management recommendations because they are calibrated for the depths of specific job roles.

Communication: In my own experience, I found that reminding the design team of the DPC Transformation roadmap twice a year was most effective for keeping morale up without overwhelming them with information. In these updates, reminding them of what they’ve already achieved, the benefits they’ve already unlocked, and what new capabilities they will encounter short term (upcoming few months) and long term (year) helped keep them as active participants in this trek.

DPC updates must be planned in relation to design calendars and when designers are most able to absorb new information. Timing them is key; avoid scheduling them when designers have many deliverables or milestone meetings. It might be more effective to have updates at smaller team meetings to help them feel like a safe space for questions.

Internal DPC newsletters are an effective way to share DPC stories across an organisation. Many companies see an upsurge in healthy competition when part of the design team’s DPC wins are loudly celebrated, be it for their speed, efficiency, or creativity. At New Balance, sharing “Ah-ha” moments, where DPC saved the day, was a great way for teams across the company to consider new ways of working.

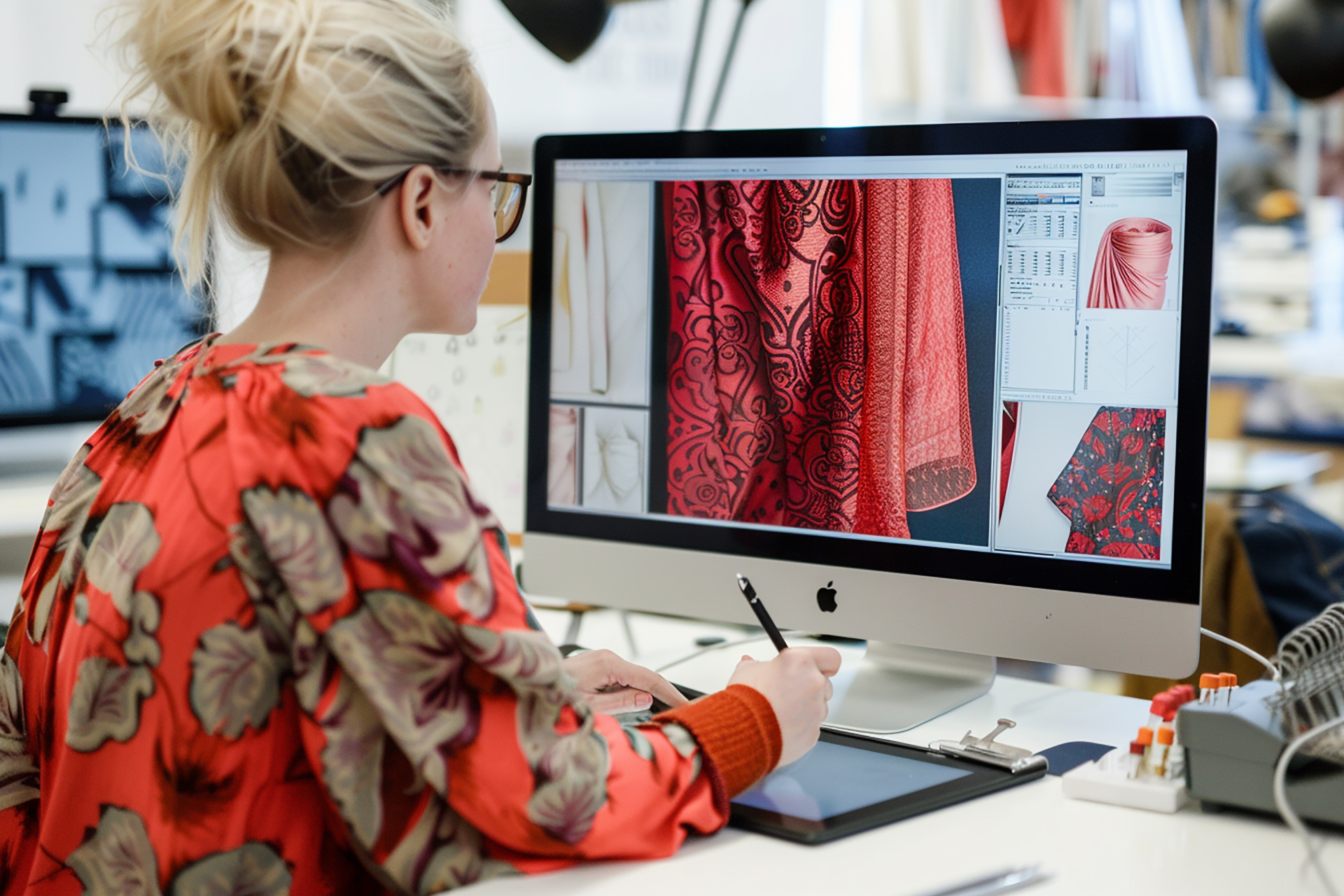

As you might expect from a strategic initiative that’s so visual-focused, DPC change leaders universally agree that images are the most effective way to communicate with designers. Your supporting materials should not be wordy and should be accessible for designers’ preferred way to access information. I found this meant putting documents and videos on a Miro board rather than in a Sharepoint site: small change in practice, but a big one in principle, because it meant meeting the design community on their home turf.

You may also need to document in more than one way to ensure the highest levels of buy-in, for instance creating a succinct one-pager in addition to a video. Designers often process information differently than other teams, so a one-size fits all approach is unlikely to deliver the desired results.

Training: If designers are expected to learn 3D tools, training should be targeted to specific DPC capabilities rather than everything that the software can do. Because as you page through this report, you’ll notice that DPC can potentially do a lot – and there’s more possibility being introduced all the time.

Comprehensive post-training support is imperative to ensure continued use and success; DPC teams need to confirm they have the resources and bandwidth to provide this assistance. Due to their calendar constraints, designers might be unable to practice as frequently as desired and may need scheduled sessions to keep new skills fresh. Where possible, remove obstacles to support designer onboarding into 3D: for instance, giving additional design support while teams gain comfort with the tools, providing complete libraries of blocks and digital fabrics to minimize frustration, and managing leadership expectations around what is feasible.

The immediacy of 3D designing has proven to be an effective enticement. Designers at a well known American clothing company are, I know, keen to design in 3D because their process enables them to receive physical samples several weeks earlier than their peers who work using traditional 2D tools. Again: healthy internal competition can be a powerful motivator.

Change agents: Designers who are embedded to promote DPC transformation, and who either start out as or become subject matter experts, are exceedingly valuable. Their ability to support their colleagues, build excitement around DPC, and provide valued insights should not be overlooked. They should come from all levels of the design organisation. The tech-savvy are often nominated for this role because of the 3D expertise, but enlisting both technically slower and DPC-skeptical team members is equally necessary. Addressing all learning speeds is more likely to get the complete team to the desired skill level. When skeptics’ concerns are resolved, their personal transformation to DPC advocate is an incredibly effective narrative for their team members.

Additionally, change agents can also help capture metrics that resonate with the whole design team: less rework, more time saved, more garments adopted, better samples the first time, fewer meetings, more successes. This network is invaluable for keeping the design team involved in the DPC transformation.

Feedback: Design’s feedback might not be for the faint of heart – expect to be challenged on process, timeline, and especially on the accuracy, reliability, and fidelity of the results – but should be actively encouraged. Most brands venerate and treasure their design community for a reason. Empathy is key; this transformation for designers can be really challenging. There will also be designers who are frustrated by how slowly they perceive the transformation is taking. Honesty is imperative.

Pretending the technology is already flawless is a kind of gaslighting, because as good as the best 3D design, simulation, and visualisation tools are, there are always areas where they could be improved – particularly when the designers in question work in a category that places a lot of stress and demand on 3D rendering or simulation, such as intimates, performance wear, or tailoring.

A DPC process manager at a prominent American retailer who I spoke to for this story told me they remind their team that “The tech is the worst it will ever be today!” This motto can also easily be extended to the processes and the team’s skill levels as well. Feedback also allows DPC teams to recognize and prioritize high value improvements. Designers appreciate that their questions get answered and problems get solved. This feedback loop creates a culture of owning the DPC transformation rather than just being along for the journey.

The expedition to DPC maturity is both a large-scale transformation, with a long timeframe, and a lot of sets of small iterative improvements that can happen in the here and now. This metamorphosis is undeniably complex, particularly for designers, who face significant conceptual and technical challenges. But the potential benefits for designers and the entire organization are profound.

Realising these benefits requires tailored change management strategies that prioritise clear communication, supportive training, and meaningful engagement at all levels. When designers are equipped with the right tools, given time to adapt, and supported by leadership, they can harness DPC to amplify their creativity, enhance collaboration, and ultimately deliver more compelling products to customers.

Thoughtful, realistic planning and empathetic leadership will ensure that the transition to DPC not only transforms processes but also empowers designers to thrive in the digital future of fashion. As Kayla Woehr, Manager of 3D Apparel Visualisation at New Balance, has observed, “After all, we are not just doing 3D for the sake of 3D – we all see the future of a better way of working!”