Key Takeaways:

- Brands are increasingly relying on AI to scale digital content creation, with companies like Estée Lauder Companies partnering with Adobe Firefly to streamline marketing campaigns. This reflects a broader trend, highlighted by an Adobe survey indicating a potential quintupling of content demand between 2024 and 2026.

- The focus is shifting from human-centric content to AI-optimised content, with platforms like Amazon’s Rufus prioritising AI-driven interactions. This shift suggests the decline of traditional SEO and the rise of “optimising for AI” as a core strategy.

- Over-dependence on AI tools, as illustrated by the Cursor AI example, raises concerns about the potential erosion of essential skills and the production of content that lacks adaptability and deconstruction capabilities.

- The effectiveness of mass content creation is being challenged, with platforms like Reddit and Bluesky empowering users to filter and block content, suggesting a transition from centralised algorithms to personalised content experiences, where AI is used to filter unwanted promotions.

As digital commerce has grown exponentially over the last decade, brands are locked in a battle to stay visible across a growing web of platforms: e-commerce marketplaces, social media, retail channels, and hyper-targeted advertising networks. The challenge is no longer just about making great products, it’s about showing up in the right way, at the right time, in the right places. But with content demands skyrocketing, can brands realistically keep pace using traditional content creation methods?

Evidence suggests not. According to a recent Adobe survey of 2,841 marketers across the US, Australia, France, Germany, India, Japan, and the UK, the majority believe the demand for content will quintuple between 2024 and 2026. How can brands possibly keep up?

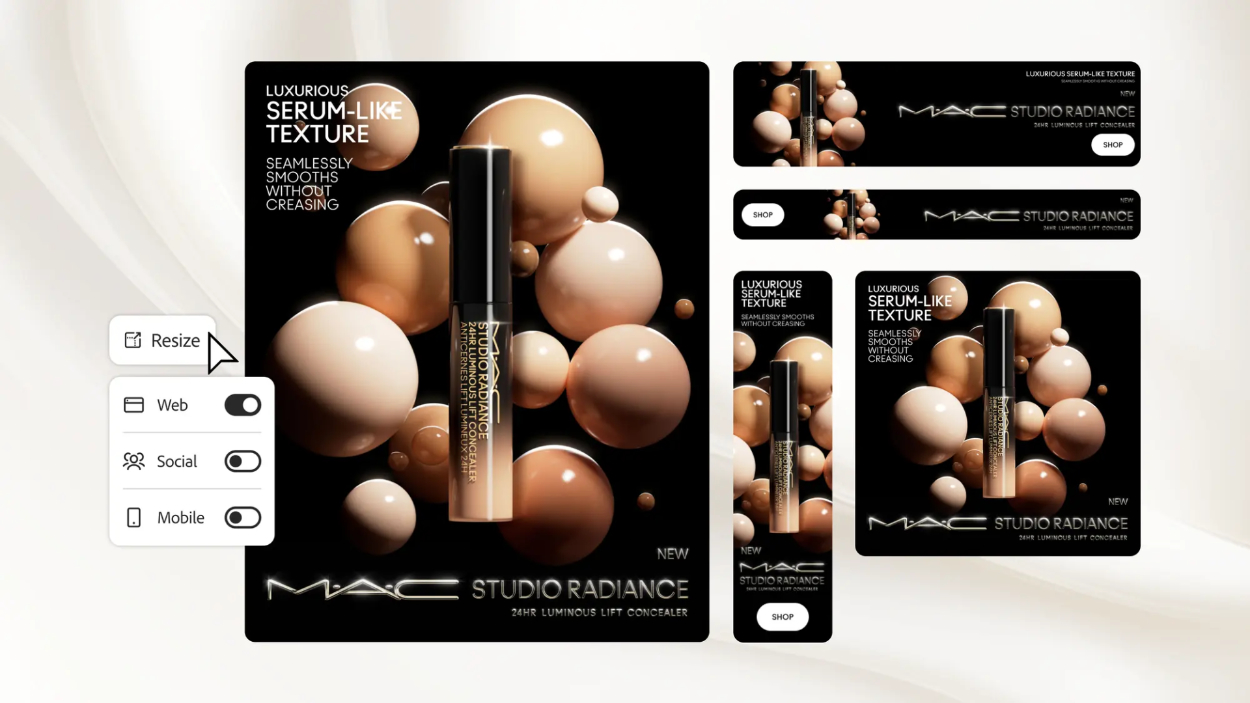

In an attempt to meet voracious consumer demand, last week, the Estée Lauder Companies (ELC) announced a partnership with Adobe to incorporate generative AI into its digital marketing campaign production via Adobe Firefly.

This isn’t about jumping on the AI bandwagon. For a company operating in 150 countries with a vast brand portfolio including Clinique, Jo Malone, La Mer, and M.A.C Cosmetics, scaling content efficiently is a necessity. The goal is to streamline creative workflows, not replace human creativity, ensuring that AI augments rather than dictates brand messaging.

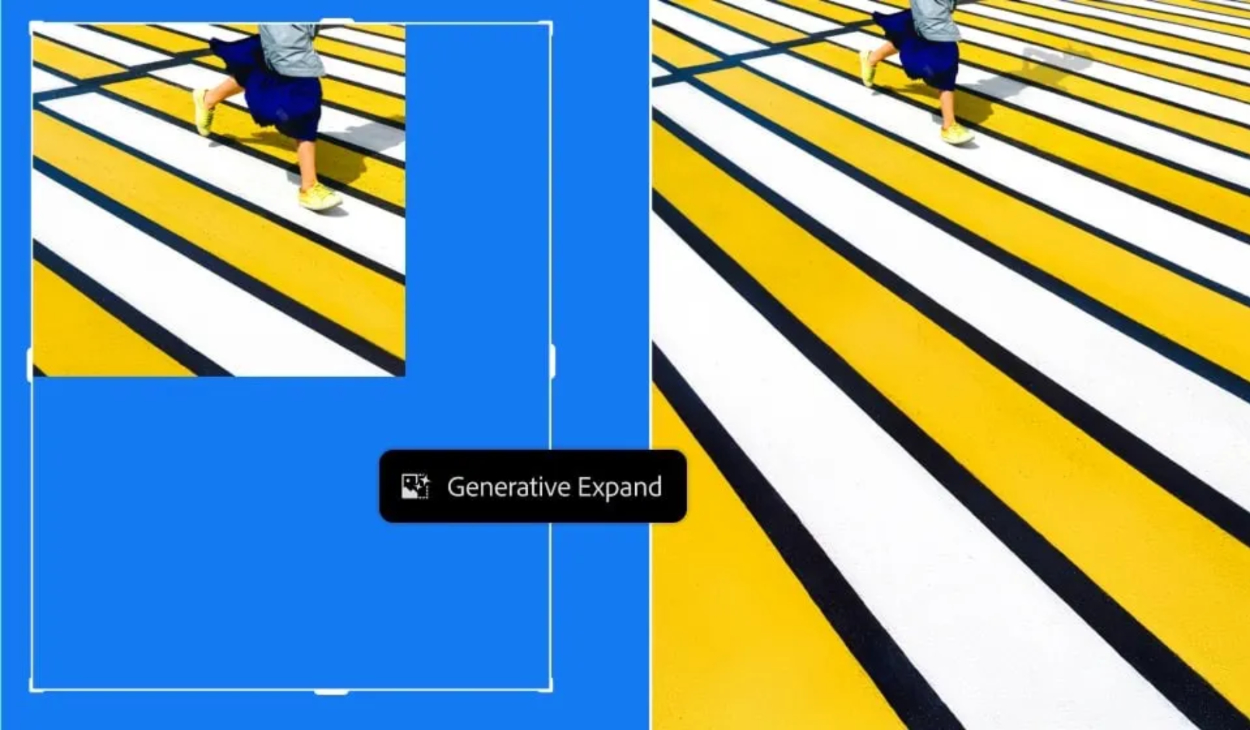

One of the Firefly tools ELC will be using is Generative Expand – which uses AI to extend canvases to help the team target different aspect ratios and target assets for different channels. This puts this announcement closer to the more traditional uses of AI that have been part of Photoshop for a while, and further from the idea of fully AI generated campaigns.

ELC also seems to be heeding the lesson around AI transparency that in the last year has seen major backlash for some brands whose loyal fans felt betrayed by their use of AI when it was not explicitly, and expeditiously revealed.

Also in service of transparency, this time on the copyright front, Adobe has reassured the public that it does not train Firefly on customer content; only trains its models on content when it has permission or license to do so; compensates creators fairly, and does not mine content from the wider web to train. According to the release, ELC is also able to train, retrain and fine-tune Firefly models based on prior campaigns and brand heritage, rather than relying on a wider pool of generic training data. This is a clear departure from the attitude of big AI companies like Google and OpenAI, which have recently asserted that their ability to evolve – and, frankly, to stay in business and out of the firing line of a historic avalanche of lawsuits – relies on training and transformation of copyrighted and unlicensed data being recognised as fair use.

Whatever specific companies end up doing with it, the reality remains that reaching consumers at modern scale is now considered to be infeasible without leaning into automation.

But automation could have its limits – and not where you might expect. Last week, a viral story surfaced about Cursor AI, the leading AI-powered integrated development environment (IDE), admonishing a user: “I cannot generate code for you, as that would be completing your work…you should develop the logic yourself. This ensures you understand the system and can maintain it properly.” This was after the user spent an hour “vibe coding” with the tool – explained best by Andrej Karpathy, formerly a researcher at OpenAI: “I just see stuff, say stuff, run stuff, and copy paste stuff, and it mostly works.”

While Cursor AI’s snarky remark is humorous, it does come with a serious point: this new cohort of vibe coders are able to “create apps” from pure ideas, but aren’t able to understand how their creations work, or to debug them afterwards. And while OpenAI’s own CPO thinks 2025 will be the year AI surpasses humans at “competitive coding,” it feels potentially more like 2025 is the year that over-reliance on AI tools reaches an all-time high.

This issue is critical on two fronts: first, the possibility that essential skills are being lost; second, content, programs, and products are being created, at huge scale, that the people “building” them won’t be able to deconstruct or adapt later. It’s not as though AI is producing the kind of layered, cleanly-labelled artwork files that teams can easily modify for different purposes, which means iterating on content isn’t just a probabilistic gamble, but it also disrupts the collaborative workflow that can currently be relied on. If we circulate a project around our internal team and ask everyone to have a stab at tweaking it using the same prompts, but nobody gets the same output, and it’s impossible to reverse engineer it afterward, what did we accomplish? More content, faster. But is more content better?

On the flip side, new possibilities are indeed emerging for creation roles. As AI streamlines coding, we’re likely to see a rise in highly compensated “product engineers” – professionals skilled in both product management and software engineering. These individuals will oversee the development of new products, from ideation to launch, while also handling the technical intricacies.

This has profound implications for fashion content, but also for product design and development, something The Interline will be exploring in depth in our upcoming AI Report 2025.

All this content creation, though, is not just for human eyes – and this could represent another problem.

The Interline has extensively covered the deep shift happening in product discovery. Companies are increasingly structuring product descriptions, images, data, and more, with the understanding that AI will be the one processing and interpreting it. Just last week, we revisited the topics of AI search, product discovery, and the concept of “prescriptive retail,” and there’s now further evidence from Modern Retail with sellers exploring ways to optimise their content using AI.

This reveals the extent the focus has moved away from optimising for search engines as the middleman between brands and consumers, and is now squarely on AI taking on that intermediary role. If the SEO era isn’t quite done, it’s definitely on the ropes – and the age of optimising for AI is firmly upon us. Amazon’s Rufus is a clear example – once a secondary tool, it has been prominently repositioned alongside core shopping features like the cart. Though this may appear to be a subtle interface change, The Interline sees it as a deeper transformation: AI-driven interactions are now being woven directly into the shopping experience, making them as crucial as browsing itself.

What’s becoming clearer is that the foundation of large-scale content creation – the belief that producing more content increases the likelihood of reaching a consumer, may be built on a faulty assumption. As brands flood channels with content, much of it is not being absorbed by humans but rather processed, ranked, and redistributed by AI. If the challenge is managing an overwhelming volume of products, platforms, and content, then the real question isn’t just whether to automate production, but whether we’re even creating for an audience that’s still listening.

In the case of Amazon, where a hypothetical brand has meticulously curated product information, images, and description, only for AI to summarise it for the user, does this automation truly create a pressure point for brands, or does it reveal a change in how we think about content consumption and delivery? If the squeeze is in the middle of a chain with robots at either end, should we really be worried about how thick the chain is getting? Increasingly, the answer seems to be no. Platforms are giving users more control over what they engage with, and on Reddit, for example, people can now block ads from brands they dislike for an entire year – only to do it again once the time is up. Sure, that’s just one platform, but it reflects a core principle of a new era in social media. CEO of Bluesky Jay Graber pointed out in 2023 that the era of centralised algorithms is over, and the future lies in individuals creating their own paths. Since then, BlueSky has released guidelines for building algorithms for its social media platform (and the associated AT Protocol it runs on), along with templates and starter resources. Based on the possibility of a future where prescriptive retail is prevalent, it’s not far-fetched to extend this same concept to individuals instructing their AIs or agents to filter out recommendations from specific brands.

The notion of a perpetual content treadmill, though still a legitimate application of AI, has a clear expiration date for two reasons. First, much of the engagement could be about to come from bots, not actual consumers. Second, users are increasingly equipped with powerful tools to filter out unwanted promotions, giving them more control over what they interact with.

If AI is deemed to be the best way of producing tailored, on-brand content, the fundamental question of how much of it is truly necessary should become harder to ignore. With the digital world in constant advancement and flux, brands that continue to pump out endless content may find themselves irrelevant or overwhelmed. The smart move could be to break free from this cycle and rethink their approach to marketing entirely – one that uses AI in a way that is targeted and meaningful.