Key Takeaways:

- OpenAI’s newest image generation model has sparked a wave of viral content online. Users have flooded social platforms with AI-generated images that mimic beloved animation styles, especially those reminiscent of Studio Ghibli. The model’s accessibility and output quality have dramatically boosted user engagement, making AI art more mainstream than ever.

- This advancement blurs the lines of copyright, as the model’s ability to precisely replicate brand names and celebrity likenesses enables the creation of realistic, albeit potentially unauthorised, fashion campaigns and scenarios, raising concerns about brand control and reputational risk.

- While AI tools offer creative leverage for designers and marketers, facilitating rapid prototyping and visualisation, they also pose a threat to brand authenticity by enabling the mass production of brand-mimicking content, potentially desensitising consumers and devaluing original aesthetics.

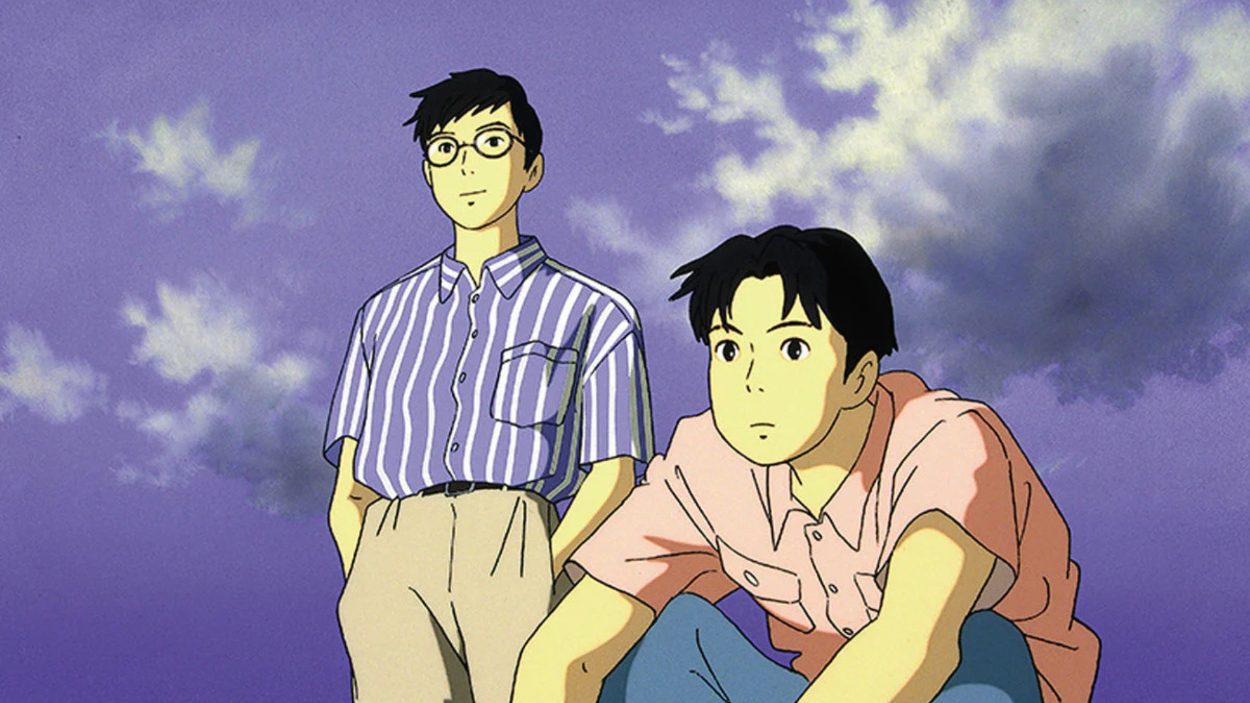

In the last few days, social feeds have been flooded with dreamlike, animated renderings of everything from the latest Grand Theft Auto to common touchstone memes. The inspiration for them was familiar: Studio Ghibli, the iconic Japanese animation house known for anime films like Spirited Away and My Neighbour Totoro. The technology behind them was new: a native multi-modal image model from OpenAI, replacing DALL-E and built into both ChatGPT and Sora, that was simultaneously more powerful and less restricted than we might have expected from the standard-bearers of consumer AI.

The virality of the images themselves was intoxicating. Brands, celebrities, friends and colleagues all jumped on the bandwagon. And the groundswell was on such a grand scale that OpenAI CEO Sam Altman claimed the service was behind a million new users signing up in a single hour yesterday. Clearly, a lot of people like making Studio Ghibli-style versions of their photos! (Claymation, Muppets, and other recognisable stylisations have also been doing the rounds.)

But the rush to meet that viral moment obscured a darker undercurrent: Hayao Miyazaki, Ghibli’s legendary co-founder and creative force, has long made his disdain for AI painfully clear, claiming that it lacks any human grounding and is “an insult to life itself”. Put-downs don’t come much more cutting than that, so it’s clear that the potential counterargument that AI honours or flatters creators wouldn’t wash in this instance.

And now, the Japanese animation industry Miyazaki’s aesthetic helped define finds itself at the centre of a growing, cyclical sort of controversy, one that brings real, urgent questions about copyright, ownership, brand and individual identity back to the fore, and that asks how far AI should be allowed to go… and who might feasibly be capable of trying to slow it down, in fashion, if they decided they wanted to.

At the heart of the conversation is a long standing question in the AI community: is emulating a style the same as infringing on it? Technically speaking, no it isn’t. Copyright doesn’t protect style, only expression. That nuance has allowed AI companies to tread right up to the line, offering users the ability to generate work that can echo the tone, shape, and soul of beloved artists, studios, and collectives without actually crossing the threshold into actionable territory.

But with this new generation of models, the line is looking a lot blurrier.

ai Prompt: Prada’s Fall 2024 collection in the style of Wes Anderson.

Where earlier versions of image generators danced around direct references, refusing to produce images of specific individuals or brand name products (deft prompters could still navigate around this issue hiding requests in ambiguity), OpenAI’s new model is surprisingly permissive. Ask for a runway show featuring Prada’s Fall 2024 collection in the style of Wes Anderson and you’ll get it. Or a portrait of Karl Lagerfeld sitting front row at this year’s Paris Fashion week – also done. What was once hinted at, or that came peering accidentally between the cracks, can now be rendered with uncanny precision. Brands, faces, and moments – all are up for remix in this new generation of image generators, at the same time that the model has taken a significant leap forwards in consistency, text generation, prompt adherence, and more.

This is, to be clear, something that determined users have been able to do with specifically tuned, open source, and / or locally-run models for a while. But the frontier image generation models from major companies and research labs have usually been released in a ‘locked-down’ state. So seeing ChatGPT and Sora happily chugging away with real likenesses and real-world brands is a surreal and sudden departure.

There are, The Interline thinks, two lenses through which it’s possible to come at this.

On one hand, we’re seeing the democratisation of cultural aesthetics and a loose definition of artistic capability. AI image generators don’t make their users into trained artists, but that doesn’t make their applications any less exciting. And today the closest analogue might be that generative image models are becoming the mood board for the masses. With a prompt and a few seconds of patience, anyone can conjure a “Balenciaga trench coat in a Blade Runner setting” or “Novak Djokovic playing tennis in a Fendi print tuxedo.”

ai prompt: Balenciaga trench coat in a Blade Runner setting.

The results of these prompts can be variable, but it only takes a glimpse at the “top” feed of user creations on Sora – currently home to X – to remind ourselves just how far things have come, as a baseline, from OpenAI’s own DALL-E 2… which was released just three years ago! It’s become a cliche to say that AI is “the worst it’ll ever be,” but weeks like this one remind us that it’s no less true for it.

For designers, marketers, and even students, generative AI tools offer extraordinary creative leverage. Designers can prototype ideas in minutes, exploring unlikely fusions of materials, silhouettes, and inspirations. Marketers can create campaign visuals without a full studio shoot. And for students and emerging designers, who often lack resources, these tools can allow them to explore and visualise ideas at the same fidelity as a high budget studio. Again: the results will often require extra work, and they need a discerning eye to curate the output, but stacked next to the empowering possibilities, creative gatekeeping very quickly begins to wither away.

While memes have dominated the early use cases of ChatGPT’s latest generator, the reality is that AI doesn’t just spit out jokes, it helps build moodboards, branding decks, pitch visuals, campaigns and concept art. In the right hands, it is absolutely a visionary tool in the literal sense: it represents the shortest distance from an idea to an instantiation of that idea that other people can see.

But in another sense, it feels bound to mean something that we have now reached effectively open season on intellectual property.

easily ai-generated fake chanel bag for demonstrative purposes only.

When the same tools are used to conjure fake Louis Vuitton X Ghibli mashups, or to put other recognisable brands in viral moments, things get murkier fast. AI generated images flooding social media could start to desensitise consumers to brand imagery and authenticity. If anyone can generate a Chanel ad, in other words, what’s left of Chanel’s brand authority other than to continue to push the creative frontier, knowing that AI will always be steps behind.

What’s more, the ability to summon photo-realistic images of real people in fictional campaigns, or worse fictional controversies, creates a new layer of reputational risk. Brands carefully cultivate not just aesthetics but celebrity partnerships, savoir faire, and a broad spectrum of other ineffable things that define a brand. A tool like the new OpenAI image generator can let people experiment with all those elements. And those are just the obvious cases, before even considering (as we did last week) how the use of AI in fashion photography, illustration, and styling runs the risk of eroding onramps and opportunities for new talent.

To borrow a metaphor itself, generative AI tools (in their compressed timeline) have been sketchbooks, helping users draw and experiment with inspiration. Now they’re starting to look more like finished output printers capable of high-fidelity, single-click style copying.

easily ai-generated fake gucci watch for demonstrative purposes only.

While fashion has not yet seen a high profile lawsuit directly targeting AI-generated designs, there are signs of growing concern. Fast-fashion retailer Shein, has faced allegations of using AI algorithms to identify and replicate trending designs, leading to legal action from artists who claim the company systematically infringes on copyrights. And it feels like a short hop from there, via new models that allow for greater accuracy, with fewer guardrails, to the point where fashion current draws the counterfeiting line.

In addition, the rise of “dupe culture,” where consumers hunt for cheaper alternatives to luxury goods, has been accelerated by AI’s ability to generate designs that mimic high-end aesthetics in seconds. While these aren’t always exact replicas, they often capture the look and feel of luxury at a fraction of the price, further eroding the idea of originality as value.

Susan Scafidi, founder and director of the Fashion Law Institute at Fordham Law School and one of the leading voices on fashion IP, highlights the evolving perception of design replication: “The diminutive ‘dupe’ has replaced more negative terms like copycat, replica, knock-off and counterfeit.” This trend, buoyed by AI, poses challenges for luxury brands striving to maintain exclusivity and protect their designs, especially as the concept of a “dupe” becomes increasingly mainstream and socially accepted.

So far, the response from fashion’s heavyweights to the ability for generative models to replicate their style, logo, colours, and products has been quiet. But as bigAI companies continue to roll out ever more powerful tools for consumer use, and as the results become more uncanny, more commercial, and more brazen, it’s fair to ask, will the time come when someone sues? After all, this has happened in publishing, photography, music, and other spheres.

From a brand value perspective, the positive case for AI is fairly straightforward to make: visibility, virality, and the ability to understand how consumers remix your legacy. By that definition, “showing up” through generative image models would be seen no differently to having a presence on a new social media channel.

But the case against it is becoming just as clear. When anyone can generate images of your products in any context, be that political, or parodic, where does control end and chaos begin?

If the trajectory continues from this week’s viral moment, we may soon find ourselves on the cusp of the first real confrontation between a fashion house and an AI company. And if that happens, it won’t just be a legal battle. It will be a philosophical one, that will challenge our ideas on ownership, originality, and the future of style in a world where machines don’t just learn from us, they imitate too.

In one sense: none of this is new. Photoshop gave people the power to recreate magazine covers, mock up campaigns, or spoof brand ads long before AI came along. Tumblr was notorious for its bootleg high fashion edits. “Inspired by” aesthetics have been the bread and butter of the internet’s creative scene for well over a decade. Even luxury brands have flirted with the remix, whether through artist collaborations or meta-campaigns that wink at their own iconography.

What’s changed isn’t the impulse – it’s the volume and velocity.

Generative AI, unfettered and more realistic and flexible than ever, doesn’t just enable parody or pastiche. It industrialises it. With fewer skills, no budget, and no gatekeeping, anyone can churn out endless campaign style images, featuring any brand, any person, and any moment, and they can do so in mere seconds. The barriers to creation are gone, but so too are the barriers to oversaturation.

And that might just be where the real problem lies. Because if style is no longer scarce, is it still special? If anyone can generate a thousand fake Gucci ads in an afternoon, what happens to the value of the real one?

As a tool, AI can amplify inspiration and accelerate creative workflows, but it can just as easily drown the market in brand-adjacent noise, confusing consumers and devaluing the carefully curated visual identities brands work so hard to protect. The dust is yet to settle on the Ghibli led AI image explosion, but when it does, we’ll be very curious to see what the landscape looks like for fashion and beauty brands and big, public AI companies moving forward.