Key Takeaways:

- Vinted has become France’s largest clothing retailer by volume, demonstrating the power of a circular business model that prioritises friction-free resale over traditional retail operations. This success is largely driven by its user-friendly interface, integrated shipping, and fee-free listings, positioning it as a behavioural layer for moving existing garments.

- ThredUp is strategically making its “Resale-as-a-Service” platform free to use, aiming to become the foundational infrastructure for mid-sized brands. This move positions ThredUp as a protocol-level solution, potentially standardising the backend of resale regardless of the consumer-facing platform.

- The surge in resale is accelerated by rising tariffs on new clothing and ongoing cost-of-living concerns, making secondhand shopping a rational economic choice. However, true long-term circularity, as noted by Hasna Kourda, Co-Founder & CEO of Save Your Wardrobe, requires an integrated aftersales infrastructure for services like repair, care, authentication, and recycling, beyond just efficient logistics and convenient secondhand transactions.

If someone asked you who the biggest clothing retailer in France is, you might guess Zara, H&M, or even e-commerce overlord Amazon. But you’d be wrong. As of May 2025, the answer is Vinted.

It’s a strange kind of milestone. Vinted after all, doesn’t design anything. It doesn’t manufacture or curate. It doesn’t warehouse stock or run fashion campaigns. Yet it now moves more clothing around France than any other entity, not by making new fashion, but by removing the friction around extending the lifespan of the garments, shoes, and accessories that are already in circulation.

To put it as bluntly as we can: this is a circular business model not just working, but working well enough that it outmatches the linear model.What’s happening here isn’t just about scaling resale, either. It’s about what retail looks like when you strip out the traditional parts – stores, seasons, held inventory – and replace them with something flatter, faster, more fluid, and seemingly better-aligned with what consumers are looking for, whether they’re making the choice based on price or principles.

Vinted has mastered logistics as a user experience. Fee-free listings keep items flowing in. The interface is stripped to its essentials, tuned for people who don’t think of themselves as sellers. Onboarding takes minutes. Shipping is pre-labelled, prepaid, and deeply integrated with local carriers. Trust is managed with simple nudges, dispute resolution kept bare bones, just enough to keep things moving without tipping into bureaucracy. The result is less a market place (though it is one) and instead a behavioural layer. A system that catches static clothing and nudges it into circulation.

Vinted aims to be for fashion what Uber accomplished for transport, or Airbnb for accommodation (and now experiences.). Just as those two companies became giants without owning cars or property, as a business model case study Vinted is scaling without any of the assets a traditional retailer would need to survive.

By contrast, eBay, once synonymous with resale, still shows its roots. General purpose auctions, fees that can be confusing, while the interface assumes a level of seller fluency most casual users don’t have. Instead, the Vinted model suggests that it’s subtraction that powers the engine (fewer decisions required, the faster the cycle turns and the more product remains in circulation).

And it’s fast fashion that fuels that engine. Zara and H&M dominate the platform with almost 200 million items listed between the two as of the time of writing. From one angle this is a positive outcome for sustainability (fast fashion represents a large share of the alarming amount of clothing thrown away every year, after being worn just a handful of times) but from the other it’s apparent that many buyers treat Vinted as a kind of deferred fitting room: buy something new, try it on, resell what doesn’t work.

This is an important distinction. As successful as it clearly is, Vinted hasn’t “solved” overproduction; it’s offering a different release valve for an industry, and a consumer market, that remains largely fixated on flooding the zone with new goods.

While Vinted captures the consumer-facing momentum, ThredUp – a resale platform that built its name on consignment but now powers take-back programmes for brands like Tommy Hilfiger – is going after something different: the infrastructure layer. Its decision, announced this week, to make its Resale-as-a-Service platform free to use is deeply strategic. As resale as a concept grows, ThredUp is aiming to lower the barrier to entry for mid-sized brands, repositioning the company not as another platform, but a protocol-level solution. Something brands can plug into, rather than build themselves. And if enough brands standardise to ThredUp’s backend, it becomes the connective tissue of resale, regardless of where the front-end consumer experience lives.

Of course, all of this is happening within a larger economic backdrop that continues to reinforce the appeal of second hand shopping. It has been widely reported that rising tariffs on imported goods have pushed up prices on new clothing and footwear in multiple regions. Combined with ongoing cost-of-living concerns, and a broader climate of financial pragmatism, this has made resale feel not just trendy or ethical but also deeply rational. This economic context does not fully explain the rise of platforms like Vinted, but it does influence their acceleration. Affordability, not ideology, has always been resale’s true growth lever.

Legacy resale platforms like eBay or Facebook marketplace still operate, of course, but they’re struggling to compete on ease and clarity. The centre of gravity has shifted. Not to brands, or even consumers, but to systems. Systems that don’t just enable resale, but are actively shaping how we engage with clothing. What gets listed. What gets worn. What gets passed on with the tags still attached.

But really scaling resale isn’t just about more efficient logistics, and it’s not just about making secondhand shopping easier. The real challenge lies in what comes after, as Hasna Kourda, Co-Founder & CEO of Save Your Wardrobe told us today:

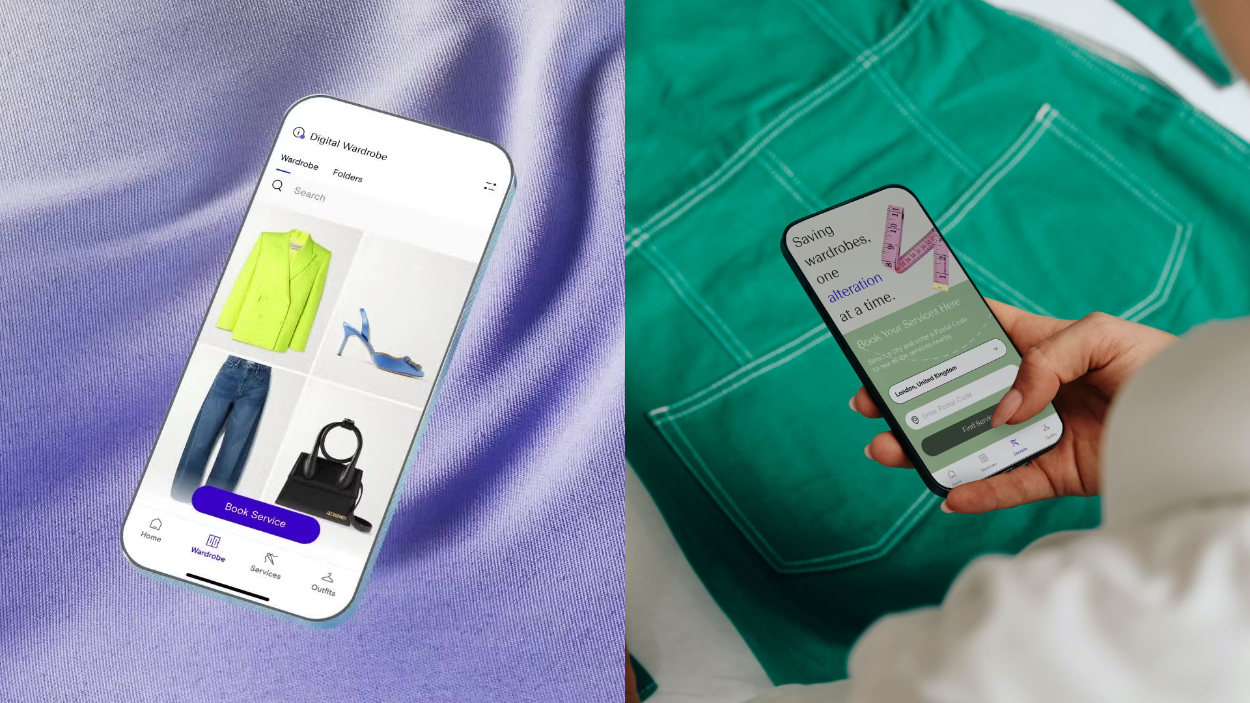

“Resale reaching the top of the retail charts in France is a powerful marker of changing consumer values, but it’s what comes next that matters. Behind this cultural momentum lies an urgent need to rethink the systems that support retail beyond the point of sale. Scaling the secondary market isn’t about adding more platforms; it’s about building a connected, resilient aftersales infrastructure where services like repair, care, authentication, and recycling are embedded into the everyday fashion experience.”

“Technology will help enable this” Hasna continued, “and AI has a role where it can enhance decision-making, streamline processes, and surface meaningful data. At Save Your Wardrobe, we deploy AI in ways that support human expertise. From detecting product faults to accelerate repairs, and improving the flow of product data to service providers. But scaling sustainably from here will require more than digital tools, it demands a collective rethink of value, responsibility, and the systems we build to keep products in use, not just in circulation.”

The shift Hasna identified isn’t just theoretical. As platforms like Vinted and ThredUp optimise for movement, there’s a risk that more meaningful forms of value (namely longevity, repair, and use) get forgotten, and those variables require systematisation the same way that the logistical and behavioural elements of the secondary market do. Because it’s important to remember that, for all the energy behind resale, behind the headlines we can see that the scaling happening in the secondary market is focused on making circularity more convenient, not necessarily making it work better. Vinted’s newly-minted status as a retail power won’t, by itself, do much to slow the pace of fast fashion – it’ll just make its afterlife easier to manage.

And for circularity advocates, real success is going to be about more than just creating a tidier way to live with excess.