Key Takeaways:

- France is intensifying its crackdown on ultra-fast fashion, exemplified by the $40 million fine against Shein for misleading discounts. This action, alongside new legislation, signals a broader regulatory strategy to make life difficult for such companies, targeting them through various avenues beyond direct environmental or labor practices, like deceptive marketing.

- Despite the rise of successful resale platforms like Vinted (now moving more clothes than any traditional retailer in France), the crucial “middle” of the circular economy – the collection, sorting, and processing of damaged or unsellable textiles – is in “crisis”. The insolvencies of major firms like Texaid Deutschland and Soex highlight the severe strain on essential textile waste infrastructure in Europe.

- Innovation Faces Commercial Hurdles, but Hope Remains. While companies like Renewcell (now Circulose) developed promising fibre-to-fibre recycling innovations, they faced significant challenges in securing long-term orders due to cost concerns and supply chain inertia. Renewcell’s collapse underscores the industry’s reluctance to pay a premium for sustainable materials. However, its rebirth as Circulose and new multi-year deals with H&M and Mango to integrate its fibre at volume offer some hope for scaling next-gen materials.

There’s something almost surreal about reading that Shein, the high speed, low cost juggernaut of ultra fast fashion, has been hit with a $40 million fine in France for misleading discounts. Not for poor labour practises, over-stuffing markets with excess product, or emissions violations, but for lying about how much money customers were saving.

There’s an element of “Al Capone getting pinned down by tax evasion” to this all, but the essentials are about as mundane as this kind of enforcement gets. Shein is accused of promising a 60% discount that didn’t stack up with reality, coming on the back of pre-sale price hikes, and consequently trying to nudge consumers into a sense of urgency that did not really exist.

Interestingly, this mechanism (misleading claims) is also being used as a crowbar to demonstrate the lack of substance behind the company’s environmental claims; Shein’s acceptance of the fine can also be read as tacit admission that those claims are either unfounded, or that the effort involved in proving them outweighs the scale of the fine.

It’s not a coincidence that this action arrives just weeks after France introduced a bill targeting ultra fast fashion more broadly. The Interline is not privy to any additional information that hasn’t already made the news, but there’s certainly a sentiment that the French regulatory bodies intend to make life as difficult as possible, via as many avenues as they can, for companies that fit their “ultra fast fashion” label. And it seems as though many of those avenues will not be directly related to the core matter – the sheer scale of the model – but will instead target brands and retailers from other angles.

But just as these levers are being pulled, with the ideal eventual outcome being less new product coming into France, the infrastructure that will be needed to support a more circular system is showing signs of strain.

As we covered last month, Vinted now moves more clothes than any traditional retailer in France, and that headline lands like a victory banner for circular fashion on its surface.

But a smooth, scalable resale experience is only part of the post-sale picture for fashion. It works for things that still hold value (the jacket someone wore once, or a vintage designer piece), that part of the system, peer to peer, clean and already sorted is relatively frictionless. It’s the other half that’s much messier. The part that’s stained, frayed, and stretched out that makes up the bulk of what we discard. The part that doesn’t sell on Vinted. The part that piles up in donation bins across the globe. And it’s this part that needs to be sorted, processed, and either broken down, or disposed of completely (ideally the former).

That quieter, more complex space is where companies like Texaid have been operating. Texaid’s remit was collecting and sorting post-consumer textiles across Germany, separating what could be resold from what needed to be recycled – none of which is particularly newsworthy, but all of which is absolutely essential if fashion is serious about building a circular system.

So when Texaid Deutschland filed for insolvency last month, not long after another large firm Soex did the same late last year, one of the major intake valves for Europe’s textile waste effectively shut down. That may just have been a single point, but it’s emblematic of a situation that could get worse if the infrastructure for circularity continues to atrophy.

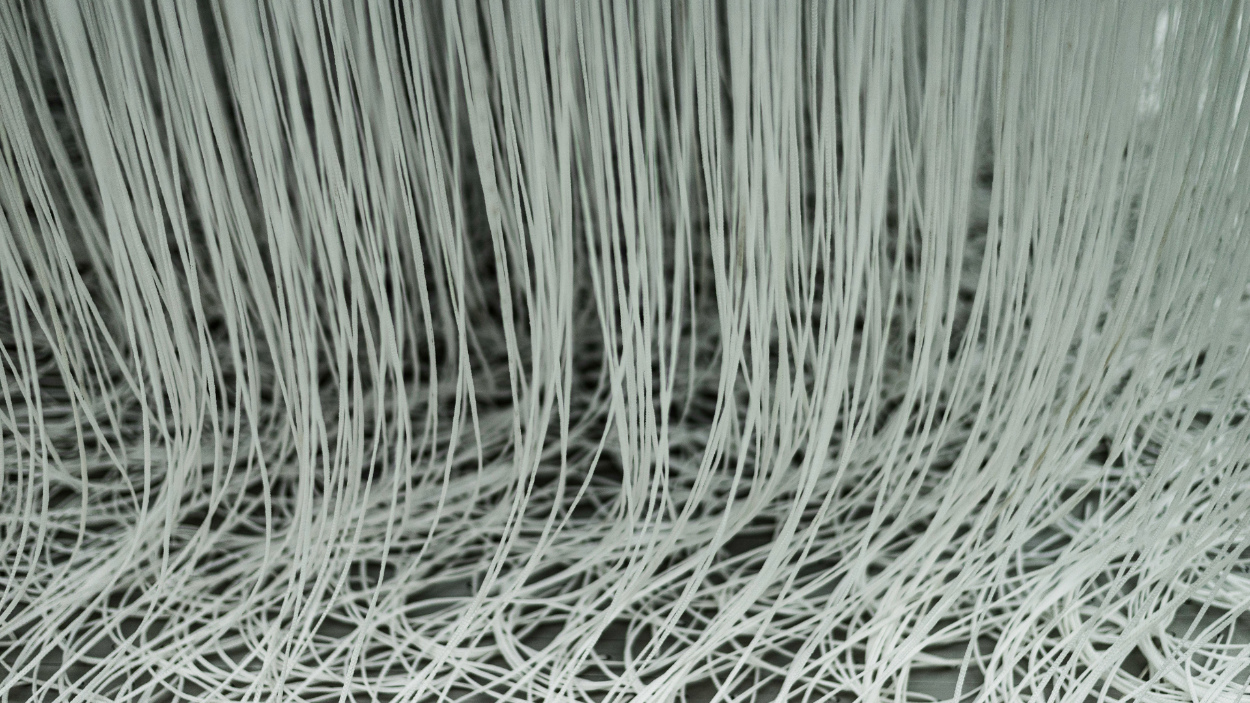

Last year, the European Recycling Industries Confederation warned that the used textiles industry was teetering on collapse. When companies like Texaid can’t stay afloat, the whole system is, for all intents and purposes, at risk of becoming blocked – even if the reasons behind a single company’s fortunes aren’t always directly anchored into the outlook for the circular model as a whole. Either recyclers get no feedstock, or they get the wrong kind. Blended fibres, elasticated seams, garments still studded with zips and buttons.

This is the unglamorous middle of the loop. The hauling, the sorting, the stripping down. The part that gets the least attention, and the least support, from consumers, brands, and even governments. And it’s not just happening upstream.

Further down the line, where fibre-to-fibre innovation was supposed to take over, Renewcell’s well-documented collapse told a similar story. It was a different kind of business – more advanced, more visible – but the outcome felt no less bleak.

Companies backed the concept: a fibre made from old clothes, ready to plug into existing production lines. Big brands publicly endorsed Renewcell. But when it came to placing long-term orders, most pulled back, held up by cost concerns, supply chain inertia, or both. As one observer put it: “Sustainability professionals in fashion remain no match for finance managers.”

Even so, a seed of the original vision has taken root again.

After the collapse, Renewcell was acquired and reborn as Circulose, who last month, launched Circulose Forward, a new platform designed to help brands integrate its fibre into real supply chains.

H&M and Mango have signed multi-year deals to integrate Circulose at volume, folding the product into their actual pipeline. This is encouraging for many reasons, and yes, while it doesn’t make the system whole, it does make it a little more plausible and provides a much needed win amid the crisis developing in the middle of the cycle.

But it’s still just one link. Production remains paused until demand aligns (targeting a possible restart in early 2026). And while the hope is that Circulose finds its footing, the rest of the chain is still showing cracks. The intake systems are straining and the middle is struggling.

The loop doesn’t work if it only looks good at the edges. Resale is seductive. Next-gen fibre is headline-friendly. But until someone steps up to rescue the middle, the boring, logistical, low-margin middle, the circle can’t be complete.

The fashion industry keeps selling the idea of sustainability, and, to be clear, regulation is a much-needed lever that has to be pulled. But if we won’t fund the sorting sheds, the waste handlers, the basic plumbing of circularity, then nothing will change long term no matter how many angles governments try to approach the problem from.