This article was originally published in The Interline’s AI Report 2025. To read other opinion pieces, exclusive editorials, and detailed profiles and interviews with key vendors, download the full AI Report 2025 completely free of charge and ungated.

Key Takeaways:

- The fashion industry’s subjective and often chaotic nature clashes with AI’s requirement for structured data and defined rules, revealing ill-prepared data foundations and process structures as a major hurdle for effective AI implementation.

- AI adoption in fashion spans four levels: from Automated Workflows (e.g., Hermes using AI for IT, Zalando cutting editorial image costs by 90%) and Functional AI (e.g., Walmart’s ‘Trend-to-Product’ reducing concept-to-completion by 18 weeks), to deeply embedded Strategic AI and nascent AI-Native business models.

- Successful AI integration in fashion hinges on augmenting human capabilities rather than replacing them, especially in creative fields. This requires identifying clear problems, having sufficient and clean data, and a readiness to re-engineer existing workflows, emphasizing a “people-led and tech-powered” approach.

The chaos, creativity and unpredictability of fashion has, for decades, been part of its elusive charm and its ability to seduce people on the outside looking in. But insiders have the battle scars to show how fashion’s inherent complexities, uncertainties, and inefficiencies, as appealing as they might look from the outside, end up in waste, financial loss, and a state of perpetual reactivity and firefighting.

No matter which part of the fashion value chain you operate in, from production, to marketing, to the sales floor, you’ve encountered the nagging idea that, when it comes to process orchestration, enterprise organisation, workflows, data centralisation and all those other backend business elements, fashion can and should do better. For a supposedly innovative and dynamic sector, ours has been relatively slow in adapting new processes and systems for the better, whether that be for efficiency or sustainability.

But there’s a new tech saviour in town. Artificial Intelligence (AI) is being hyped up, right now, for its ability to come to the rescue and solve fashion’s most serious ailments by imposing structure and order where other big technology pushes have failed – or by, at the very least, helping the people who work in fashion to extract real insights from disorder. In the process of rolling AI out, though, fashion is learning (the hard way) how ill-prepared its data foundations and process structures are, and how different they look from what AI systems expect. While fashion has thrived, against the odds, by tasking people with reconciling different priorities and different workstreams, it’s less than clear whether applying the same philosophy to AI – which appears to operate best in domains with structure and well-defined rules – will work.

And that disparity could become even more visible when we think about how AI struggles with improvisational problem solving and cultural nuance – both of which are highly prevalent within fashion. Right now, a gap in both knowledge and practice exists, a murky grey ball of confusion, and at the centre of fashion’s ambitions for AI, is the idea that it might be able to impose order on the industry’s cluttered workflows. Between the two, how are we going to determine whether human-led or machine-led knowledge should penetrate specific workflows (i.e. design, forecasting, sourcing)? Not only that, but when to integrate AI is another big question mark. Should fashion organisations wait till they need to medicate with AI (the point at which they feel as though their human-only capabilities are falling short of market demands and upstream complexities) or should they adopt it as a more preventative measure?

Or to put it another way: what is fashion, an industry renowned for succeeding in spite of an ongoing mess behind-the-scenes, actually supposed to do with AI? Are the two worlds on a collision course, or can they actually complement one another?

If fashion is from Venus, then AI is from Mars. Fashion is by its very nature, subjective, non-linear, emotional and intuitive – ‘human’. This is mirrored throughout many of its core workflows from garment design and fitting, to brand identity and personal selling. David Lindsay (Co-Founder Yallus, former CTO LVMH, Farfetch, NAP) suggests there is a “human attraction to thinking that creativity is in some way indefinable”. Conversely, today’s ‘narrow’ AI can be characterised as objective, logic-based and focused – ‘machine-like’. Some say ‘soulless’ – a critique I’ll revisit shortly.

Today, therefore, a gap exists, Gala Marija Vrbanic (Founder and CEO of TRIBUTE BRAND) identifies that ‘the biggest gap remains in the creative execution. Specifically, the ability to replicate individual taste. In fashion, personal sensibility drives originality and impact, and AI still lacks the nuance to fully mimic that.’

But is this an intractable disconnect between two very different entities? Or could the clash between how fashion operates and how AI works actually be just like the many personality clashes we have seen before, between buyers and merchandisers, or creatives and developers?

Whilst these two beasts are stereotypically like chalk and cheese, they do actually complement each other, as each has opposing strengths and weaknesses. When brought into a hybrid workflow with the right timing, for the right task and for the right purpose, it can be argued that together, they are better. After all, fashion has successfully wrestled with the same tension between spontaneous creativity and rigid commercialisation basically forever.

To help illustrate how this might all play out, the table below shows four levels of AI Adoption, with the overarching function that AI plays at each level and a division of operational use cases. I have delineated the different domains according to whether AI currently excels or struggles with the task, to help determine where AI augmentation / automation could be the answer, and also where hybrid workflows might be better.

Table: Fashion Value Chain Activities X Human Vs AI Led Workflows

| Level | Main function of AI | Fashion Use Cases where AI Currently Excels | Fashion Use Cases where AI Currently Struggles |

| 1. Tactical AI | Automation (operational efficiency | • design ideation • pattern creation • production processes (cutting, stitching and assembly using AI-driven robotics) • cloth simulation and colour matching • editorial and advertising campaign creative • digital ad targeting | • creative execution • design without biases • garment fitting for diverse body shapes • quality control and testing |

| 2. Functional AI | Augmentation (data driven decision making) | • virtual sampling and prototyping • trend prediction • material selection • inventory forecasting • supply chain optimisation • virtual fitting rooms and try-on experiences | • materials sourcing • cultural nuances • production logistics • supplier negotiations |

| 3. Strategic AI | Integrated Intelligence | • personalised customer service • personalised search and recommendations | • brand vision creation and identity storytelling |

| 4. AI-Native | Operating Layer | • N/A | • N/A |

Looking at the first, most basic level of AI adoption, automated workflows are primarily undertaken to achieve operational efficiencies, or to achieve the fabled freeing up of creative time by easing the administrative burden. These are culturally uncontentious areas for brands to explore, since the vast majority of people will readily accept the aid of technology to reduce or eliminate anything they see as busywork.

One example of this is Hermes who recently explained they are using AI only for “limited applications, including IT service optimization, supply chain support, and internal reporting via external cloud-based platforms”. Hermes also clarified that “creative and artisanal processes will remain human-led”. This approach is conservative, sure, but also safe and logical for a heritage luxury brand of its stature and scale – one that venerates its creatives.

At the other end of the market is Zalando, who just reported that 70% of its editorial campaign images were AI generated in Q4 2024. This innovation led to a cost reduction of 90% and a speed to market of 5 days rather than 7 weeks. A solid implementation success case which will undoubtedly have a ripple effect to other brands who will adopt their methodology. But also a clear step over a line where AI is imposing order onto creative tasks in a way that uplifts the efficiency of those tasks, but at an uncertain potential cost to creative and human expression.

Looking at the next level of functional AI, which is probably the most frequently adopted form of AI within fashion right now, we see AI aiding and augmenting decision making and ideas at speed with large data sets – huge and hugely complicated corpuses of information that are simply beyond the realms of human capability to effectively analyse. And this is also the type of AI use case that transcends in-house teams and begins to spill out into optimising not just the way products get made and sold, but how prospective buyers engage with and experience those products, and the brands behind them.

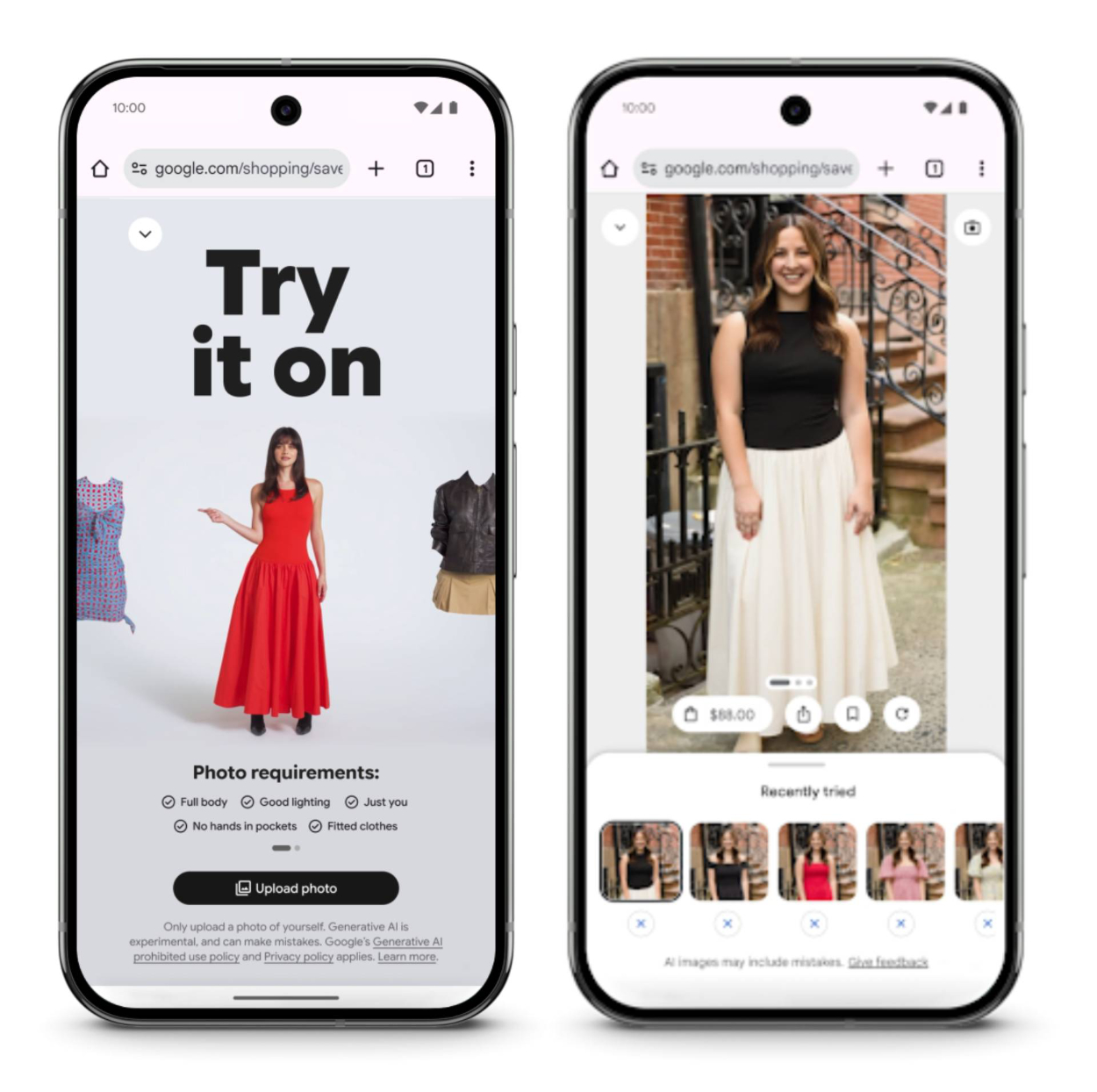

The recent launch of Google’s ‘AI Mode’ for shopping is a textbook example of this, as it includes contextual search, price comparison, virtual try-on and an agentic checkout experience. Time will tell how successful this new mode will be, although most features are only available in the US so far.

Another more creative workflow application of functional AI is designer Norma Kamali’s use of AI as a tool for brand reinvention. Kamali collaborated with Maison Meta on a proprietary model to re-invigorate several of her iconic designs. Interestingly it was Kamali who proclaimed after the project that “AI doesn’t have a heartbeat, it can’t replace human passion, but it can enhance creativity in ways we’re only beginning to understand”. Two very different worlds that seem to work well together – even if the taxonomy to describe that interaction is difficult to define.

On a more straightforward workflow optimisation track: last month Walmart promoted the results of an internal proprietary AI product called ‘Trend-to-Product’. Using both AI and generative AI it analyses global trends, creates mood boards, provides collection names, colours and textures as well as outputting a supplier tech pack. The results here were similarly measurably to what Zalando saw with its structured roll-out: Walmart states it has reduced their concept to completion cycle by 18 weeks, describing this new workflow as being ‘people-led and tech-powered’.

Continuing up the ladder, the next level of adoption is strategic AI, where it is embedded deeply throughout the organisation as integrated intelligence. Platforms like the heavily funded Daydream or new-kid-on-the-block Phia are current examples of this. Each of their business models rely on strategic AI to disrupt product discovery and search (Daydream), and price based and sustainable decision-making (Phia). These are not single function or one-domain applications; these are platforms that are proposing to use AI to replace, or at least refurbish, the fundamental pillars of fashion’s business model.

So it’s notable that there are fewer fashion brands adopting this depth of practice as yet, since this perhaps tells us where the frontlines are currently being drawn between what types of structure fashion is willing to let AI impose upon it, and where that imposition becomes too strong.

A question to ponder here is why? Does this merely reflect the maturity of this tech adoption in the time to date, or is there also a correlation between adoption maturity and scale. In general, small to medium enterprises (SMEs) are more nimble, dynamic and therefore more able to adapt to change, corporates, are the opposite. However, SMEs within the fashion sector are often traditional and generationally owned (i.e. a fabric mill) or forward thinking and single person (i.e. an emerging designer). For them to introduce AI into their workflows, it’s a challenge dependent on the level of innovativeness and operational discipline of the owner as well as the amount of time and financial investment needed.

The highest level of AI adoption can be described as AI-native, whereby it forms the operating structure of the business and is autonomous and self optimising. There are no high-profile fashion businesses as yet who fit this profile, however examples outside of the sector are visible, especially in software where companies like Lovable, Notion and Synthesia have gone all-in on describing themselves as AI workspaces and full-stack AI platforms. No doubt the first AI-native fashion brands are already being created, although the ambition of handling the entire product lifecycle, end-to-end, with AI is a far higher bar in an industry that makes physical products.

So we know roughly what fashion could be aiming to do with AI, how the industry can segment the different stages of adoption, where the industry is likely to be comfortable allowing AI to add top-down structure to its workflows – and where it won’t. Lastly, let’s try to answer the when question.

It sounds trite to say it, but a fashion business should implement AI when it identifies a problem to be solved, Lindsay agrees stating “AI must have a purpose, like when it’s a need, or when it’s able to do something you can’t”. Secondly, on a practical level, the business needs to have enough data to train/feed it. Thirdly, there should be a minimum level of digital maturity and workflows already in place; AI cannot be applied on top of dysfunctional governance. If many processes are undocumented, then digitisation, documentation, and cultural change management should happen before AI implementation. Vrbanic reflected to me that, “The decision to integrate AI into our [Tribute Brands’] commercial products came when the technology reached a quality standard that matched the expectations of our community”. Joshua Young (Transformation Consultant, former Director VF Corp and Nike) adds a final fundamental prerequisite, that “brands must be willing to change the way they work before AI capabilities can provide substantial benefits”. He goes on to explain “continuing to work the same way while expecting AI to solve your problems will yield negligible benefits. To unlock real value, companies must first reengineer their processes”.

So, can AI impose structure on fashion’s chaotic workflows? Yes, it most definitely could. But if it is ‘forced’ or adopted as a vanity metric then it’s likely the new structure won’t embed and the output or results could be worse than they were before. Anyone who’s been part of a technology implementation project in the past will recognise these parameters, and will be familiar with how easily the target outcomes can be missed.

Does AI need to bring structure to fashion? From both a market competition and a sustainability perspective, also yes, because fashion, despite attempts to rein it in through legislation, continues to pursue strategies defined by growth. However as Young suggests, perhaps the structural changes are best orchestrated by the organisation first, and then fine tuned with AI after. At least until the finetuning becomes better handled by non-humans.