[Featured image: AI-generated]

Key Takeaways:

- Western Executives have returned from trips to Chinese factories shocked by the level of automation powering some of its manufacturing base. China’s industrial robot deployment has reached a scale unmatched globally, with its installed base exceeding two million units in 2024 and over 295,000 new units added that year, according to the International Federation of Robotics (IFR). This automation is expanding beyond auto/electronics into logistics and textiles, driven by state strategies like “AI+ Manufacturing.”

- For brands, automation promises stability and control, reducing the safety risks, labour disputes, and reputational fallout that continue to shadow manual production. Yet in fashion, technical limits remain. Sewing and finishing still resist full automation, keeping large parts of the supply chain dependent on human labour.

- While automation promises stability and efficiency, its adoption creates significant, unmeasured social disruption. The closure of factories and loss of employment, as seen with Haiti’s garment industry collapse, unravels communities, creating a human cost that is not captured in standard ESG reporting.

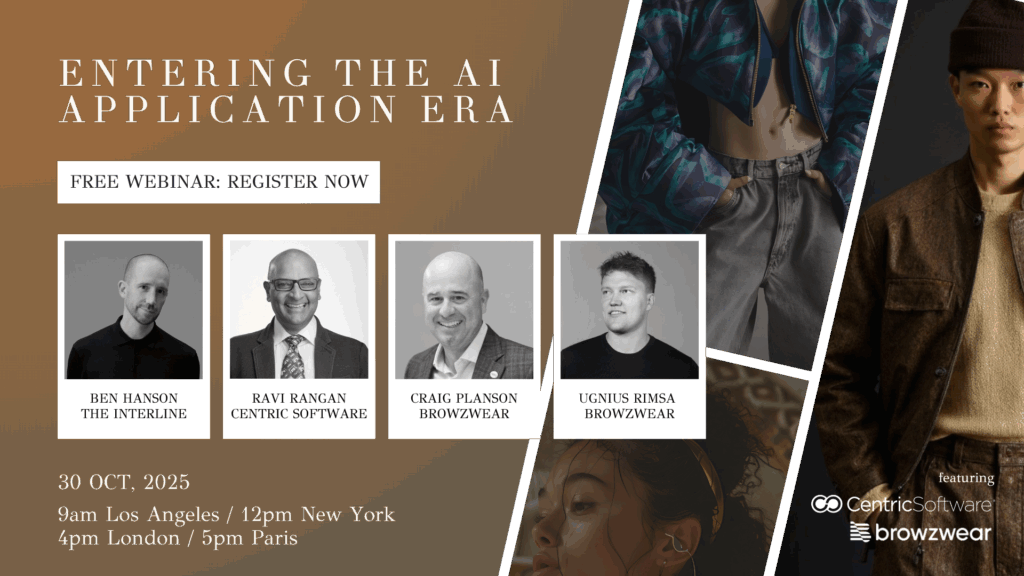

Register for the Webinar: Entering The AI Application Era

AI in fashion has moved past exploration and into implementation. On 30th October join The Interline, Centric Software, and Browzwear to examine what that shift means, from aligning AI with real business processes to understanding where automation, data, and design now intersect.

Join us as we explore:

- How AI is evolving from open-ended experimentation to enterprise adoption.

- The importance of aligning AI initiatives with business rules, domain-specific data, and measurable outcomes.

- The balance between generative and analytical AI, and where each delivers value.

- How automation, accuracy, and a new ecosystem of models are reshaping fashion’s next phase of digital transformation.

Automation is spreading through manufacturing, changing what work looks like and where it happens. The question now is how far it can go.

Across a range of industries, Western executives are returning from China uneasy about what they’ve seen. In a new Telegraph report, leaders from companies including Ford, Fortescue, and Octopus Energy describe factory tours that left them startled by how little human labour remains on the floor. Production lines that once relied on thousands of workers now run with robots welding, assembling, and moving materials through full cycles. A few staff remain, mostly to monitor screens or check equipment. Some plants now operate day and night, lights kept low because the machines simply don’t need them.

What sounds like science fiction has, in some corners of China, seemingly become the norm, and the reality that many of these visiting Western executives are realising is that in China, industrial robot deployment has reached a scale unmatched anywhere else. According to the International Federation of Robotics, the country’s installed base of industrial robots exceeded two million units in 2024, with more than 295,000 new units added that year. What’s more, Asia accounts for nearly three-quarters of global robot installations, and China represents the largest share. The country also leads in production of the same hardware it’s consuming: domestic manufacturers supplied roughly half of the world’s industrial robots last year.

The concentration of automation is also no longer confined to automotive or electronics. Industry data and official programmes show it extending into sectors such as logistics, heavy machinery, and textiles. State strategies including Made in China 2025 and AI+ Manufacturing frame automation as national infrastructure. As of 2025, over 40 percent of the world’s “Lighthouse Factories” – industrial facilities recognised by the World Economic Forum for advanced manufacturing – are located in China. The result is a manufacturing base that increasingly operates through software control and predictive systems rather than direct human management.

Inside the factories, the difference is plain to see. Visitors describe production lines where robotic arms work entire shifts without pause, sensors track quality in real time, and logistics systems feed material automatically. One executive put it bluntly: “There are no people — everything is robotic.” Chinese officials have said they hope to “share the fruits of sci-tech progress with the world,” a phrase that captures both the ambition and the presentation of these facilities as proof of national progress. Domestic robotics firms have enabled that scale. China’s dominance in both robot production and deployment gives it vertical integration few other economies possess.

And while China appears to be leaps and bounds ahead of the competition, the entire global robot market reflects this acceleration. The IFR reports that industrial robot installations have doubled over the last decade, reaching 542,000 new units in 2024. Robot density, that is the number of robots per 10,000 manufacturing workers, has also doubled in that period. Some industries lend themselves to this transition more easily than others. Automotive production remains the most automated sector, followed by electronics, but textiles and apparel are beginning to register on those charts too – and not just in the small, confined experiments we see in research labs, but rather in larger-scale industrialised applications.

Chinese contract manufacturers, the factories that produce garments and components for global brands, have been integrating numerically controlled cutting, laser engraving, and certain types of programmed stitching into their lines for a long time. In some facilities, machines now handle decorative stitching or denim finishing that once required teams of workers. Fully automated sewing remains difficult because fabric slips, stretches, and folds unpredictably, but automation in supporting tasks such as cutting, inspection, and alignment continues to expand.

By contrast, where China’s factories edge toward full automation, much of fashion’s wider supply base still depends on human labour, and the cost of that dependence keeps showing up in headlines. In Bangladesh this week, a fire tore through a garment factory on Dhaka’s outskirts, killing at least sixteen workers who couldn’t reach the locked exits. The country’s garment industry, which employs millions, has recurrently suffered such disasters despite successive safety reforms – something we tried to capture in “How Many Casualties Is Clothing Worth?” more than two years ago.

In Italy, the details differ but the risk remains. Prosecutors are seeking judicial supervision over Tod’s, citing labour abuses by suppliers and subcontractors. Court documents name workshops in Marche and around Milan, that produced components like shoe uppers or uniforms for Tod’s. Workers there were paid between €2.75 and just over €3 per hour, well below national contract rates, with deductions for food and lodging.

Further along the cycle, even the “green” corners of fashion replay the same script. Investigations in Panipat, India, found workers processing discarded fast fashion into new yarns under severe air pollution and minimal safety controls. In Turkey, similar conditions were identified in waste facilities receiving material from Europe. The “circular economy” model has replicated many of the same labour structures as conventional manufacturing, demonstrating how dependence on cheap manual processing persists where automation is absent.

It’s no wonder automation looks like progress when the alternative keeps generating such unsavoury news. Human labour has a habit of generating lawsuits, headlines, and outrage, none of which are particularly palatable for the brands that are faced with them, but none of which are seemingly severe enough to prompt a fundamental reevaluation of the business model. Automation on the other hand, promises none of that. It’s stable, quantifiable, and easy to fit into systems built for reporting safety and compliance. In short, machines don’t create the same liabilities that humans do. Whether they create different liabilities… time will tell.

Even so, the limits remain clear. Brands may want automation for its stability, but the materials and fabrics themselves continue to decide how far they can go. Even as machinery improves, the change is gradual, not transformative. What emerges is partial mechanisation, not replacement…at least for now.

All of this, of course, looks at the problem through the cold light of corporate efficiency. It measures safety, cost, and control, not consequence. The equations that justify automation rarely include the people left outside its walls.

The human cost is harder to plot. Automation doesn’t just take jobs, it also unravels the communities built around them. When factories mechanise or shut, the lives of the people who worked in them are turned upside down. None of that shows up in ESG reporting, which records productivity gains but not what’s lost in the process.

We saw a version of that in Haiti. As we reported last week, when dozens of garment factories there collapsed under new tariffs and the weakening of trade programmes, the social effects were immediate. Tens of thousands lost work, and the communities that depended on those wages started to break apart.

Brands still talk about collaboration between workers and machines, but the partnership is often lopsided. Once a task is automated, it rarely reverts back. Labour remains only where technology is unfeasible or uneconomic, and, at a whole-industry level, fashion continues to pursue labour at the lowest practical cost as margins are squeezed from other sides

Today, both systems, automated and labour-based, now run side by side. China continues to scale automation across its industrial base, while labour-dependent production in South and Southeast Asia persists under tighter oversight but with continuing glances behind the curtain revealing a human rights record that might be trending in the right direction, but is still moving slowly.