Key Takeaways:

- Noom and Haut.AI launched “Future Me,” a generative AI feature that shifts predictive skin simulation from a consumer-facing beauty try-on tool into a coaching and motivational feature for wellness. By visually projecting how a user’s skin may change over time based on lifestyle habits, the tool makes abstract health information tangible, testing the role of AI in driving long-term behaviour change.

- Personalisation is expected in beauty and wellness, but user trust in generative AI depends on framing. When predictive tools present outcomes as guidance, with clear labels, opt-ins, and visible intent, they feel collaborative; when they slip into persuasion, they lose credibility.

- The use of predictive generative AI in a wellness context, like Noom’s, positions the technology as a useful, monetisable value exchange rather than pure advertising. Its success depends less on absolute accuracy and more on maintaining a guidance-oriented tone to avoid consumer pushback seen in purely synthetic marketing.

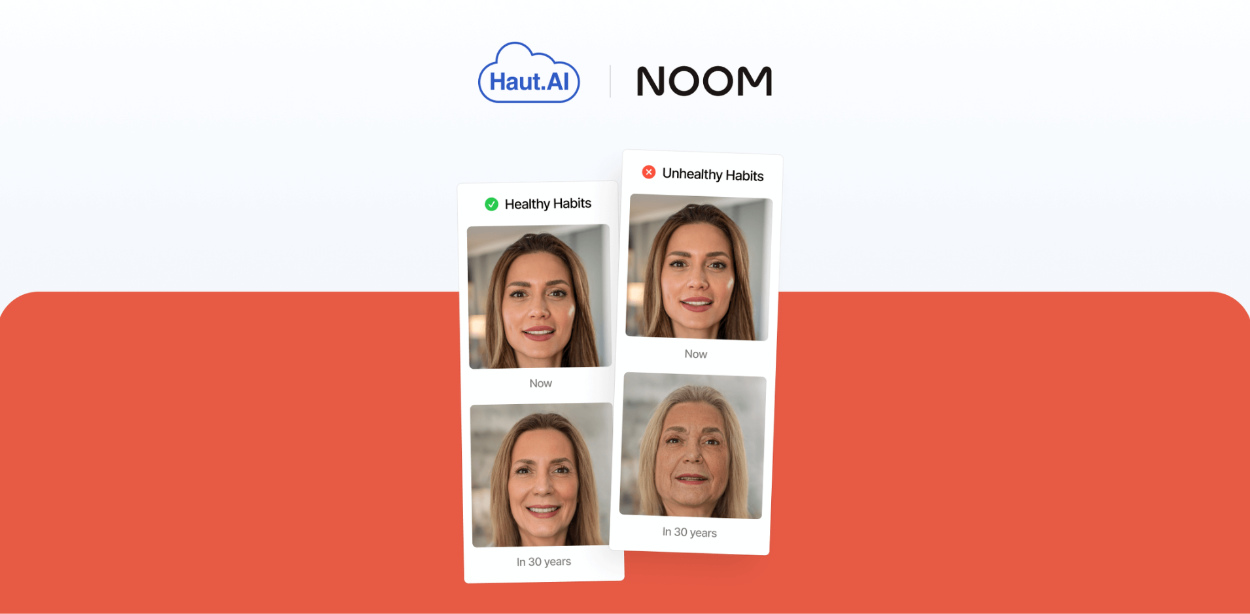

Noom’s recent partnership with beauty-tech firm Haut.AI, became a product this week with the launch of “Future Me”, a predictive generative application that provides a visual projection of how a user’s skin might change over time, and contrasts the effects of different habits on those visual outcomes. The model claims to draw on information about sleep, hydration, and sun exposure to translate everyday habits into visible outcomes. The result is a feedback tool designed to make health information easier to understand via a visual prompt that’s intended to make the outcome of present-day choices more tangible.

Noom, for the uninitiated, is a personalised weight loss service that prioritises psychology, coaching, and progress tracking. So this is an interesting application of the “SkinGPT” ageing model, in that it demonstrates one set of potential visible outcomes from a complex set of systemic, whole-body variables. And it’s doubly interesting because, unlike the beauty companies that would be the typical users of this technology, Noom is only tangentially selling the solution.

Within Noom, the model sits as a coaching feature and a provider of motivation, which may or may not land depending on how receptive you are to being shown a heavier, older version of yourself. Elsewhere, though, the same predictive model will likely wear its business hat; the same system that demonstrates the potential negative outcomes of not drinking enough water can, in another context, prompt you to buy a moisturiser that promises mitigation.

Personalisation of marketing and claims is widely expected in beauty and wellness, yet surveys also show caution about AI-generated or AI-altered imagery. Noom’s use of generative AI, though, seems as though it will hit differently to the synthetic “virtual models” that we’ve seen pop up in campaigns, or even the virtual try-on apps that represent probably the biggest consumer-facing push for generative AI. It’s still generative, but it’s being used to explain and turn habits into feedback. Clear simulation labels, opt-ins, and easy exits all help users read the tool as guidance, not a suggestion with an agenda. None of that changes what the model can do, but it changes how the experience feels – and studies of user response to predictive AI back that up, people are more comfortable when outcomes are framed as possibilities, not promises.

Haut.AI’s own site says the system “boosts marketing efficiency” and “increases conversion rates,” when it’s applied through established channels where shoppers are keen to translate abstract-feeling claims into personalised ‘reality’. Any tool in this space will inevitably earn its keep by linking understanding to behaviour, whether that’s a new habit, a consultation, or a purchase.

That’s why the tools finding traction in this space tend to be the ones that represent more of a value exchange – a way of connecting a brand, service, or product to a person, that carries with it an implicit promise. Diagnostic or advisory systems, from skin analysis to personalised recommendations, fit this rubric.

But when generative models start to stray into pure advertising, with its very lop-sided value exchange, they run the risk of falling into a new – or at least more heightened – pushback against AI, which is, itself, coming from brands rather than from consumers.

Some brands, like Aerie or Polaroid, have lately started to lean into a “human-only” message for their marketing and their products, because they believe that buyers value the human touch over the artificial one – even if that artificial touch is grounded in scientific prediction.

By this logic, consumers are not “afraid” of AI, and nor do they “hate” it – they simply see it having narrow value in non-creative use cases, and they expect companies to be open about when and where generative models are used.

That’s a balance that Noom and Haut.AI are testing, and one that’s likely to get tested even further across more product-oriented applications in the near future. Right now, it positions generative technology as useful, monetisable, and largely uncontroversial, while keeping its commercial purpose implicit (nobody using Noom will be under illusion that they’re not being sold a service, after all).

Predictive modelling is creeping into daily apps because it’s highly functional. The deal users appear to accept is pragmatic, opt in, observe, decide, move on. Whether that deal holds depends less on accuracy than on tone. Or, in other words, whether you believe that “future you” is someone you want to meet on your own terms, or an AI model’s. The answer is probably less clear-cut than we expect.