Header Image Credit – Tesla

Key Takeaways:

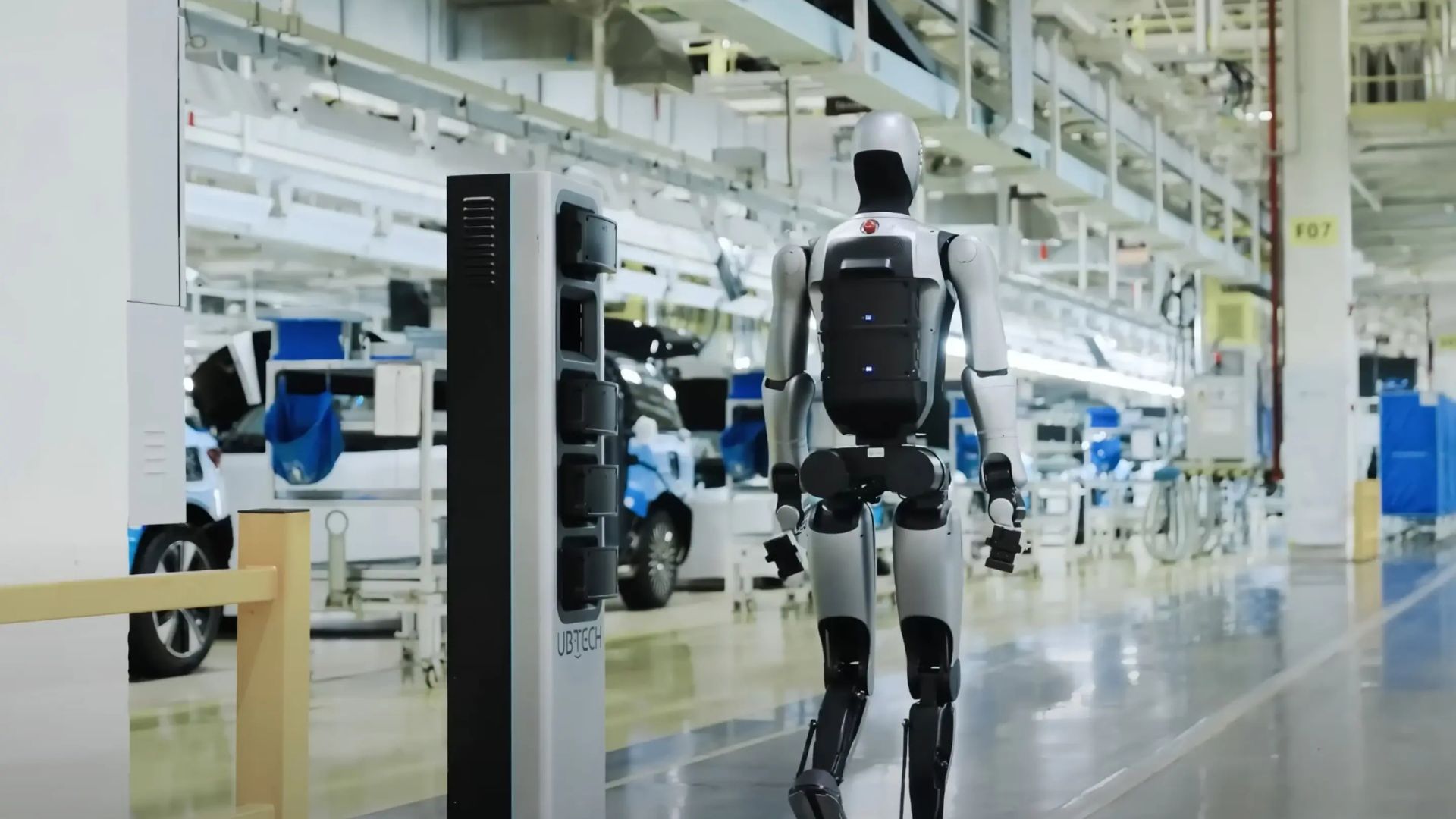

- The World Robotics Conference in Beijing showcased how quickly China’s robotics sector is accelerating, with state sponsorship driving a push for global leadership in embodied robotics. Unlike traditional industrial automation, these AI-driven machines can adapt to less rigid environments, making them viable for complex, variable tasks such as those in fashion and beauty manufacturing.

- The market for this type of robotics is poised for explosive growth. Morgan Stanley estimates the humanoid robot market could reach $5 trillion by 2050. This growth comes as global labour pools shrink, with automation being seen as a lever to amplify human capacity and maintain production output.

- Commercial adoption is already underway. In a recent deal, Chinese car parts manufacturer Fulin Precision purchased 100 embodied industrial robots. The supplier claims its A2-W model can match a production line’s monthly output in a single shift, signalling a major productivity gain and the technology’s readiness for real-world use.

The World Robot Conference in Beijing this weekend underlined how quickly robotics (in every sense of the word) is advancing, and, as many commentators have noted, how far ahead China has pulled. Already the manufacturing hub of the world, despite the build-out of sourcing and production capabilities and infrastructure in other markets, China, on the surface at least, is positioning itself as the centre of the next wave of robotics adoption and, consequently, potentially securing its place as a production powerhouse for another era.

That’s a big, blanket statement, of course – and it’s worth questioning through fashion and beauty-specific lenses, as well as through the prism of what actually constitutes maturity in robotics and manufacturing automation at a time when single-market consolidation and centralisation is being touted as the lever that other major economies could pull to compete against the Chinese hegemony. Plenty of countries, after all, have strong robotics credentials: Japan, South Korea, and Germany are the go-to examples. But in terms of raw volume and state-level sponsorship, no market seems to be moving faster than China.

The fact alone that Beijing is hosting the World Robot Conference is a signal in and of itself, the support of the government in embracing the technology is another, and, even more pertinently from a manufacturing perspective, large scale orders for industrial embodied robots (a robot embedded with AI-centric software that is framed as an actor in the world, capable of adapting to less rigid environments, rather than a rote automaton) are actually starting to arrive. When money changes hands for real products, it’s usually a safe bet that we’re talking about more than just vaporware or years-away pilots that will likely never see commercialisation without some serious compromises.

And behind the purchase orders, that change in capability from structured to unstructured automation is especially relevant for apparel in particular, where (at least beyond the well-established realm of automated nesting and cutting) the different variables of materials and operations do not lend themselves to easy robotisation the way more rigid, engineered products do.

It’s would be easy to see these two divergent approaches to robotic automation: one built for the factory floor and structured applications; the other for, well, so far splashy demonstrations. But under the surface, the same advances are going to drive both forwards, even if they don’t end up converging: AI perception, adaptive control, and the ability to take on work that’s more complex and less predictable are all advances that apply to both shapes. Whether it’s a pair of arms on a production line or a head, torso, and legs, the leap that analysts are predicting is less about form and more about how flexibly it can work. (Although the fact that we have spent centuries building factories designed to be navigated by human beings means that humanoid shapes may be a good initial stepping stone, even if they are less efficient.)

Morgan Stanley has already estimated that the humanoid robot market could reach $5 trillion by 2050, while Elon Musk has said Tesla’s Optimus robots could one day be its main product offering. (Although at least one of these can be read as a wild stab in the dark by a desperate company.) And it’s certainly the case that many industries – fashion and beauty amongst them – are looking for a new foil against upstream uncertainty and fragility.

It’s not as though the fragility of global production is a new story, though. And industries – again, fashion and beauty included – have been working to address it through a wide set of traditional means. In a global economy, what happens in one part of the world ripples quickly across the rest of the system, and as a result, that system is becoming progressively hardened to those effects. But aside from moving locations, lobbying for social change, or fundamentally re-evaluating how those industries compensate their upstream workers, there are very few ways to compensate for a shortage of people.

That shortage is also, statistics tell us, not likely to be a temporary thing: successive generations are set to shrink the available labour pool, and automation is widely seen as a way of amplifying human capacity and capability.

It can supplement human labour in markets where skilled workers are scarce, and, if the idea of allowing embodied robots to be piloted (for want of a better word) by AI pans, the latest robotics systems can even switch between tasks quickly enough to make smaller, more diverse production runs a reality. The news may come from a completely different industry, and be more about centralising pieces of the supply chain, but it’s no coincidence that Ford, originator of the modern assembly line, is proposing to move beyond that paradigm and create what it calls a “new Model T moment”. If you need a sign that we’re entering a different era of manufacturing, this could be a strong one.

As we mentioned at the top, this week brought the first large order in China for embodied industrial robots, and that order comes from the automotive industry. Car parts manufacturer Fulin Precision has bought 100 of them. By industrial standards, that’s not an enormous number, but for this category it is notable. The company says its chosen model, the A2-W, can hit the monthly output of a production line in a single shift. Even with the usual level of exaggeration, that’s still a significant productivity leap.

Equally important is the suitability of the infrastructure into which these machines will be deployed. Many of China’s factories already have digital systems and physical layouts that lend themselves to integrating advanced robots with comparatively little disruption, combined with talent pools that are already well-versed in translating the requests of domestic and overseas customers into reality through part-digital means. That could make adoption an easier proposition, more of a potential drop-in upgrade than a complete overhaul, which in turn could shorten the time from investment to productivity.

In this sense, China’s position is basically unique. As the world’s largest exporter of manufactured goods (with a rapidly expanding domestic consumer market), it has both the scale and the incentive to push automation forward, and the convergence of robotics and AI means that the latest machines could operate in environments once deemed inappropriate for automation. In fashion, specifically, that means tasks such as small batch work or mixed material handling.

If this distinction between structured work based on scale and more flexible automation seems a bit abstract, agriculture offers perhaps the clearest precedent. In British Columbia, a company called 4AG has produced a robot to tackle mushroom harvesting, a subcategory of farming that has been disrupted by chronic labour shortages. It’s become cliche for older generations to say that “nobody wants to work any more,” but The Interline thinks it’s probably reasonable that few people are drawn to the idea of working in damp, dark warehouses around the clock, to keep up with harvesting fungus – a crop that grows year round and can double in size every 24 hours, demanding constant monitoring.

With those constraints in mind, the company has deployed its AI powered mushroom-picking robots across Canada, the U.S., Ireland and Australia, and they’re already working 24 hours a day, with no breaks required. This allows yields to stay consistent when they would historically have been affected by numerous variables, with worker availability being the primary one.

Now, nobody is suggesting that cutting, making, and sewing clothing is comparable to harvesting mushrooms, but the broad parameters and principles have at least something in common. Tasks once thought too delicate, too variable, or too dependent on human judgement can, under the right conditions, be automated in a way that improves reliability and predictability without also requiring other elements to scale in a way that’s net depletive to the goal of maintaining or increasing throughput without sacrificing margin.

This is also a conversation that’s inextricably tied to geopolitics. Many countries have talked openly about either protecting or revitalising their domestic industrial capabilities and capacity, from steel and cars, to food and cosmetics. These commitments are, either explicitly or covertly, part of the debate around either deglobalisation and nationalism (depending on the perspective of who’s in charge). In the U.S. the promise to “bring manufacturing back” has been a rallying cry for the Trump administration that, by and large, doesn’t appear to be backed by actual state sponsorship the way China’s approach has been. The unspoken image in much of that rhetoric is a return to the job-rich, labour intensive plants of the mid 20th century, but if China’s trajectory is the guide (and if Ford is right to bet on a post-assembly-line future), the manufacturing sector that evolves or returns may look very different. It’s likely to look more like the warehousing, logistics and distribution industry today: highly automated, less layout intensive, and staffed by a smaller human workforce focused on managing and maintaining advanced systems (like the ones multinational grocery company Ocado employs to pick and pack a third of all products) rather than carrying out the bulk of production.

This creates a tension between the domestic political value of job creation and the economic logic of international competitiveness. These two types of capital are more likely to strain against one another than to be pulling in the same direction. If automation is the baseline for global manufacturing competitiveness (and there is mounting evidence it will be), then the facilities that open in Western markets under the banner of “reshoring” may not bring the level of employment the public has been led to expect – particularly when these facilities are paired with the export-heavy balance sheets of most single-nation success stories.

None of this is to suggest that robotics will, in the very near term, replace human labour wholesale in fashion or beauty. Even in the most heavily automated facilities, humans remain essential for oversight and the kind of dexterity and decision making that machines still struggle to replicate. But the “ChatGPT moment” for robotics, the point at which capability, cost, and proven return on investment combine to drive rapid, widespread adoption, may be closer than many anticipate. And, just like ChatGPT, the downstream effects of that shift could be messy, far-reaching, and multi-generational.

Automation, then, is not a universal solve-all for upstream volatility. It can’t prevent climate driven raw material shortages, or insulate a business from all instability, but as part of a broader strategy, it is a lever with tangible potential that’s clearly prompting the world’s biggest and most advanced actor to pull it with enthusiasm.

The World Robot Conference was, in one sense, a showcase of ambition, a vision of what robotics could become in the next decade (or faster). But it was also a stage in which the gap between vision and reality began to look a lot more narrow, and the forum where one nation flexed a muscle that basically every other country is also working to build. How that changes the sourcing and production landscape for our industries remains to be seen, but it seems clearer than ever that, when you walk through tomorrow’s factory doors, the interiors could look very different in relatively short order.