Key Takeaways:

- Announced this week, Sephora’s My Sephora and Condé Nast’s Vette are a new attempt to fold the parasocial pull of creators directly into the engagement-to-checkout funnel in fashion and beauty. The intent is for followers to feel like they’re buying from someone they already “know,” while backend infrastructure (incorporating AI in some capacity) works to scale up ‘micro-shops’ to support those transactions.

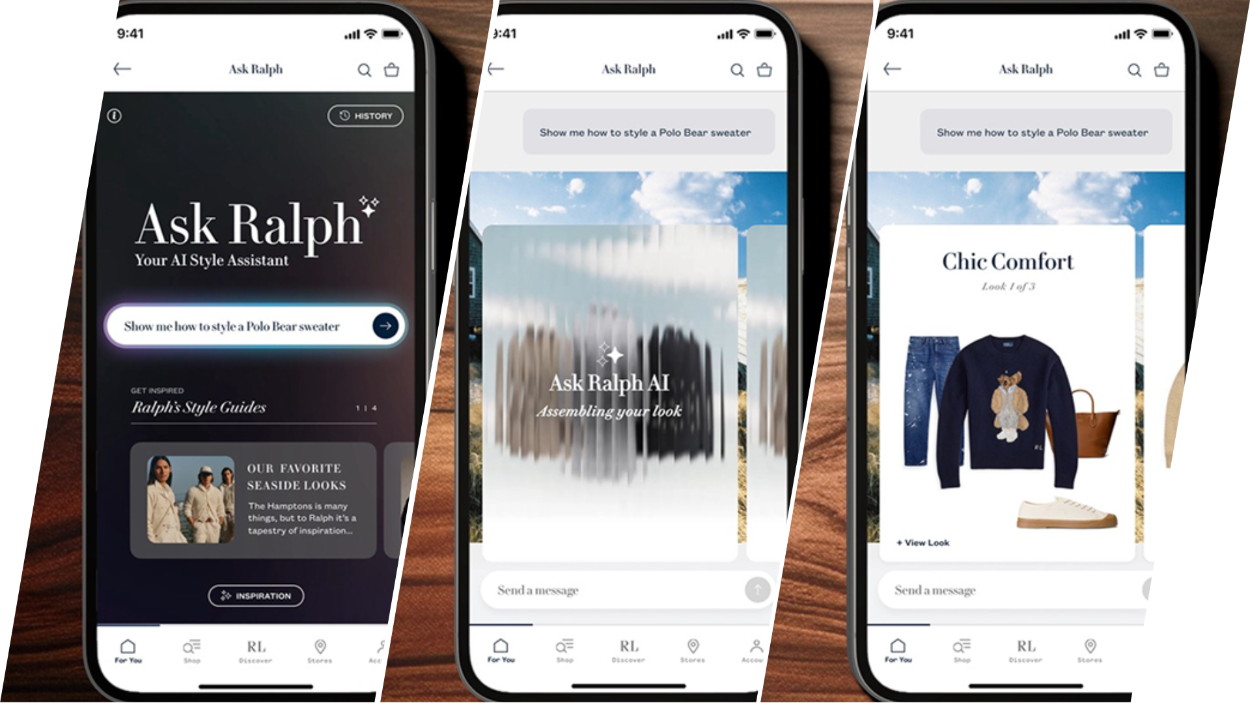

- Elsewhere in AI as a mediation layer between brand and consumer, Ralph Lauren’s new chatbot, Ask Ralph, launches., The chatbot can answer open-ended, relatively fuzzy styling prompts, reinforced by decades’ worth of well-curated Ralph Lauren lifestyle imagery.

- As selling power further devolves from traditional media and even established storefronts, specialists who currently hold a lot of sway over fashion and beauty channels are continuing to advocate for the value of their contributions – especially as AI pilots continue to expand?

This week, both Sephora and Condè Nast have announced plans to create influencer led storefronts. At first glance, this sounds like the latest in a long series of industry experiments in the form and function of digital commerce, but the undercurrent goes deeper: for a long time, venerable institutions, especially in publishing, enjoyed gatekeeper status, but the social era seems to have devolved that power so comprehensively that, instead, the smart money is being placed on creating the funnel and the infrastructure that allow the current tastemakers (i.e. influencers, who themselves may yet prove to be on the wane, if AI has any say) to curate and sell directly.

The key word there is “direct,” because to date the influencer economy has hung together through an accretion of indirect channels and means. Influencers and creators have long monetised their audiences through affiliate links, discount codes, brand marketing deals, and organic exposure earned through social posts. Instead, Vette (Condè Nast’s new platform) and My Sephora are proposing to fold those relationships into the retailer’s own ecosystem. Instead of directing followers to third-party sites, or using tracking links to monitor traffic, the ‘storefront’ lives inside the platform, and the checkout happens under the brand’s roof.

There’s a bunch that’s relatively new here at the platform level, but actually precious little that’s novel or requires any deep interrogation at the cultural level. It’s well-established at this point that people like to buy from other people they have already let into their lives, just as they once placed trust in magazine editors and curators whose publications they gave pride of place on their coffee tables. For years now, the appeal has not been to any kind of centralised authority, but to someone whose routines we watch, whose voice we recognise, and whose presence feels familiar – even if they’ve never met.

There are big philosophical questions about the health of so-called parasocial systems (one-sided and half-imagined relationships between online personas and the people who follow them) but the practical and commercial ones have been tested to death.

Watching someone else’s skincare routine – especially if that someone else looks like you, and you feel as though you share some lived experience – is proven to lead to purchases, and the connection (illusory or not) is strong enough to move some serious money around.

Needless to say, very few influencers have the chops or the desire to build storefronts of their own, and while some creators in that space have certainly partnered with technology and service companies to create backends to support their ambitions, but the proposal from the platforms announced this week is for AI (in a very general sense) to sit behind the persona, fuelling recommendations, personalisation, and presumably payments – the latter of which we covered in last week’s analysis of the announcement of the AP2 protocol for agentic AI checkout.

Essentially the argument is this: real people will forge and maintain the connections, but behind the scenes thousands of micro-shops will be spun up to substantiate the idea that the consumer is buying from a person they trust.

But given just how far the big platforms have already started to push on the idea that trust can be vouched in AI models almost as easily as it can be in people, it would be naive not to ask the question of what might happen if that influencer is something other than human. And this week provided some further evidence that, while generative influencers are still an edge case, AI stylists as a mediation layer on top of the brand experience are well worth trying. Last week, Ralph Lauren launched Ask Ralph, a digital styling assistant that can answer open-ended prompts in the vein of “what to wear to a September wedding”, or “how to build a casual look for the office”.

The underlying mechanics aren’t immediately clear, but the assumption is that this uses an LLM rather than the broad-bucket matching we’ve seen from “AI” assistants in the past. There’s nothing fundamentally new here on the experience level, but unlike prior attempts to jam IBM Watson into eComm landing pages, the difference is felt both in capability (if there’s anything LLMs can do well, it’s keep a conversation going and then reference training data) and cultural evolution. Chatbots are no longer “weird,” and neither is there much stigma still attached to the idea of asking an AI to provide style advice. In the immediate wake of the high-control, high-availability release of Nano Banana, so many people are asking AI models to visualise a new rug in their room, or swap their hairstyle, that it feels almost mundane.

And on a deeper level, millions seemingly already use AI systems for companionship over utility, and if parasocial trust is built from interaction and the temporary illusion of access, then it isn’t impossible to imagine an AI assistant developing a similar kind of resonance.

Provided, of course, that an AI influencer could act as though it was able to perform the same kind of curation and tastemaking that separate the most impactful influencers from the morass of lifestyle creators. And in this regard, there’s likely to be no real substitute for brand archives – assuming they’re properly curated themselves. Ralph Lauren, of course, has an advantage here in the form of decades of brand mythology-building and a war chest of lifestyle photography. For this specific interaction, no one is going to be fooled into believing an AI stylist is real, but they might feel like the experience is elevated because of the set dressing. In that sense, Ask Ralph isn’t really about winning over a user’s affection but instead more about a brand finding new ways to extend a world it has already made believable. The trust is earned, but it belongs as much to Ralph Lauren’s long built imagery as it does to the assistant itself. The AI isn’t winning people over so much as it is doing a more convenient job of pulling from cachet already won.

Valentino’s recent Vans campaign sits at a different pole altogether. It was promoted as the house’s first fully AI-generated campaign, built from assets pulled out of recent runway shows. The images were technically new, but the source material that fed it was the work of a human cast. Models who walked, photographers who shot, stylists and crews who assembled the looks. Valentino says the project used the material with the informed consent of the models and other talents involved (a detail that distinguishes it from the murkier experiments we’ve seen elsewhere). Even so, the underlying test remains the same. It remains to be seen whether the Valentino name alone is enough to anchor trust in images built with tools now open to almost anyone, or whether buyers of a very different stripe to the mass market audience will rebel.

Recent “spec ads,” created by independent artists without brand involvement, show how easy it has become to mimic the look and feel of a luxury campaign. And depending on where you stand on the IP spectrum, or how old you are (The Interline newsroom is certainly divided when it comes to seeing AI-generated spec work as either creative chutzpah or cheap commodity) those experiments can land very differently. Yes, the images were owned by the brand in this case, but if everyone is using the same tools then what happens to the implicit trust that, if a campaign carries the Valentino stamp, it still counts as a Valentino original?

Crucially, what happens when influencers go down the same road?

The answer to that question is also where the British Fashion Model Agents Association is seeking to draw its own line around the ubiquity of AI tools and the data used to train them.. In its new petition, signed by thousands of models, the group argues that faces and bodies are not free raw material. Models, as we all know, sit at the centre of an ecosystem of stylists, photographers, make-up teams and studio crews. If their likenesses can be archived, remixed, or redeployed, then both provenance and associated labour are thrown into question. Valentino may have secured consent for its campaign, but the petition insists that what’s missing is a wider framework, one that guarantees models and other contributors remain more than data in a system built on their work, and instead become compensated parties in a fair value exchange.

Line these stories up, and you get a rough spectrum of where the industry thinks trust should live. Vette and My Sephora fold human presence into retail systems, keeping AI beneath the surface. Ask Ralph puts AI at the interface but leans on the scaffolding of Ralph Lauren’s long-built aspiration. Valentino pushes AI into the spotlight, relying on brand authority while reworking images from its own archive. And the BFMA petition reminds us that trust has limits when the people who provide it feel undervalued.