Key Takeaways:

- The debate between “green growth” and degrowth continues, leaving fashion brands with an uncertain strategic horizon to aim for.

- If the outcome is a scaling-back of product variety and volume, brands and retailers may need to turn to product-anchored services as a way of bridging the revenue gap.

- In the longer term, these service offerings are likely to move in-house; in the near-term the landscape is set to be defined by partnerships and white-label service handoffs.

The concept of degrowth in fashion has been getting a lot of attention recently, as sustainability becomes an increasingly pressing issue, and as it becomes progressively clearer that more radical action is needed to meet emissions and waste targets.

The concept is straightforward. In theory – retailers must strike a balance between profitability and planetary boundaries, and consumers will, as a consequence, need to reduce their consumption levels and adopt more mindful shopping habits. Ideally, those two scenarios would co-occur, since each will need to drive the other.

However, the practical implementation of these solutions raises two crucial questions. First: are the giant retailers, who are responsible for the lion’s share of fashion’s footprint, actually willing to voluntarily scale back, to prioritise people and planet over profit, and to do it within the commercial structures that govern big public enterprises?

Second: are consumers willing to let go of their desire for constant change and trend-chasing? To put it as bluntly as possible, people currently like acquiring new things, and the majority of them will need strong incentives to curtail their natural wants.

The answer to these questions is not a simple yes or no. From a consumer perspective, many of us claim to shop with a conscience today. But in practice, those values are often easily discarded when the desire for newness, or following trends intervene. This is referred to as the ‘attitude-behaviour’ or ‘action-value gap’ – terms that highlight the disparity between what people say they want to do (become more sustainable), and what they actually do (acting more sustainably). This was also clear at a national level at COP28, where the conflict between the pressing need for environmental actions and the phaseout of fossil fuels, and the prioritisation of commercial interest led, ultimately to diluted agreements.

The idea that people say one thing and act in a way that’s incompatible with it is nothing new, but for fashion, it is a problem with substantial consequences. Consumers are probably not, of their own volition, going to buy less at a whole-consumer-cohort level. And brands that are held to account by shareholders on upward momentum and profitability are also unlikely to electively reverse direction.

With that in mind, is degrowth feasible, or is it fundamentally incompatible with the idea of a successful, profitable fashion industry? This is a question William Green, Co-Founder of menswear brand LESTRANGE (which focuses on essentialism), asked in a recent article.

In this article, I am going to approach this question from a different perspective, by exploring how services such as repairs and rentals, can help retailers balance profitability with sustainability to potentially achieve the dubiously-defined ‘green growth’ – moving away from being a primarily product-based fashion industry to a product and service-based one, and therefore plugging the hole in their balance sheets that comes from making less products, by adding and extracting value from the extended ecosystems that exist around those products.

Services to the rescue

Product-related innovations, such as using next-generation materials, and more efficient and less resource-consuming production processes can undoubtedly help reduce the overall negative environmental impact of the fashion industry.

However, product-related innovations can only help in limited ways. This is because, by definition, they are still solving only the edge of the problem: lessening the impact of extending the lifecycle of individual products, without moving the needle on the quantity of those products that arrive in the market.

This is where services can step in. As non-material offerings, services provide a unique and more sustainable approach to delivering on consumers’ demand for new products, which often require a significant amount of resources, even when produced sustainably. Services enable retailers to decouple their growth from continuous production, and also have the potential to help fashion retailers maintain, if not increase their profitability by acting as new revenue streams.

A few examples of services that fashion retailers can offer are repairs, upcycling, (dry)cleaning, and renting. None of these are new and ground-breaking innovations, but there is an upswing in the adoption of service offerings in addition to products by fashion retailers. The good news here is that although these services are reliant on products, their demand can continue to grow irrespective of the desired lower production rates in the future, as there are already billions of products in circulation and millions are being produced as we speak. In line with this, services can contribute to sustainability by keeping existing products in circulation instead of disposing of them, and thereby offering a potential solution to fashion’s significant waste problem.

Adoption of service offerings can be achieved by various retailers; from online-only to brick and mortar, luxury to fast fashion, big to small. Of course, for some, it would be easier than others, and their approach would certainly differ, but is nevertheless a viable option.

A great example of a luxury fashion retailer offering services is Selfridges, who has set itself a target for almost half its transactions to be based on resale, repair, rental or refills by 2030. They have already taken steps to achieve that through collaborations with third-party businesses – such as Sneaker ER for shoe repair and cleaning, Hurr for rentals, and most recently, their partnership with Sojo, a clothing alterations and repairs platform – which will be in their London store permanently.

Service offerings in-house vs through partnerships

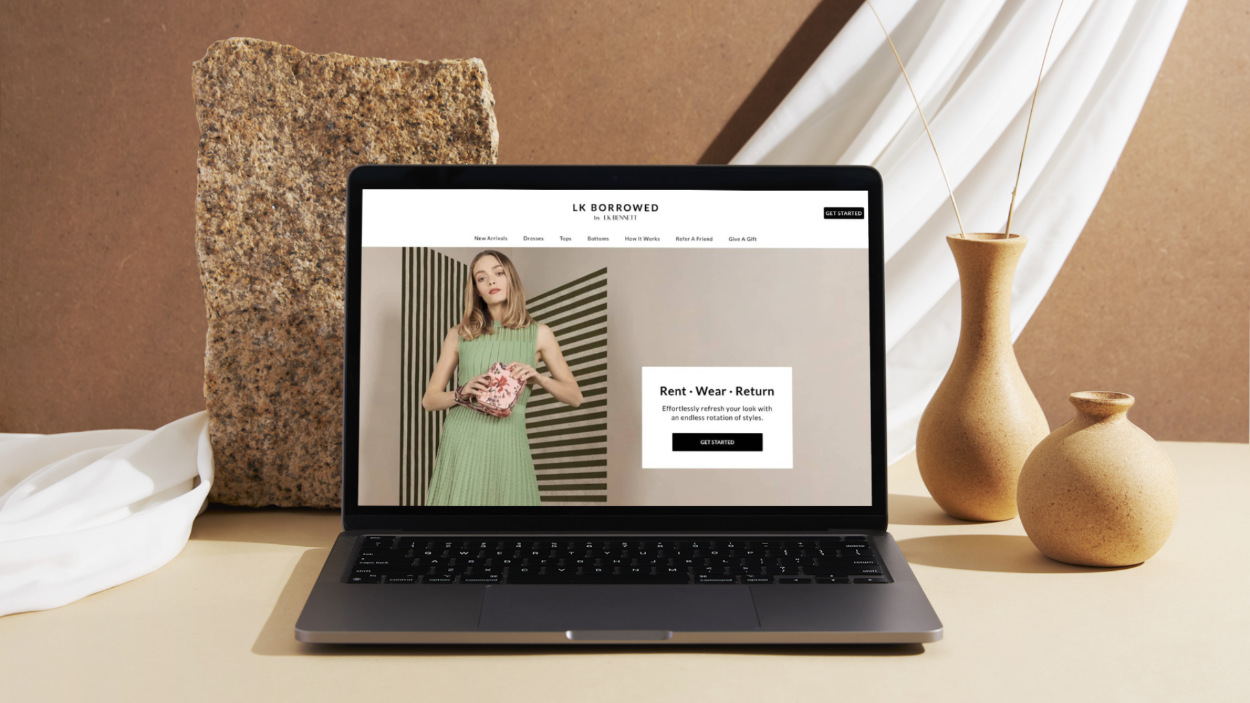

In addition to collaborating with third-party companies to offer services like Selfridges, fashion retailers can offer services in-house. LK Bennett, a premium British fashion retailer, started offering a rental subscription service called LK Borrowed, allowing customers to rent LK Bennett pieces for various occasions, from casual to special events, instead of buying brand new items. This enables LK Bennett as a retailer to limit and reduce their environmental impact while making profit from their subscription fees.

I interviewed the Digital and Marketing Director at LK Bennett, and asked them how their customers have responded to their rental service, to which they said: “Since its launch in Summer 2021 our subscription rental service LK Borrowed has been extremely well received. Customers who subscribe to the programme love that it allows them to refresh their wardrobe regularly at a lower cost and in a more circular way. The programme has continued to grow as more and more UK customers see the value in rental being part of how they consume fashion”.

The rental apparel market is certainly gaining momentum and is expected to reach $7.45 billion by 2026, which presents a great and perhaps an obvious opportunity for fashion retailers to explore. In line with fashion rental’s projected growth, the Digital and Marketing Director at LK Bennett said: “As rental becomes more widely adopted by UK customers, we expect to evolve the rental offering to give further choice and flexibility in subscription options. Rental is a relatively novel proposition for most people, so we intend to keep listening to customers on what they want from the service and evolving it to meet their needs”.

As the rental and fashion services landscape evolves, retailers face an important decision: do they offer these services in-house, or do they partner with third-party platforms? Both approaches certainly have their pros and cons, and their suitability depends on the specific retailers.

To shed light on the different approaches, I asked the Digital and Marketing Director at LK Bennet about offering rental services in-house, and its benefits as opposed to working with third-party platforms. They explained that: “offering the service in-house allows us to own the end-to-end experience and customise it to the needs of our customers. We also work with partners like Hurr on a wholesale basis to offer a small selection of pieces for one-off rental, but LK Borrowed allows us to easily offer the whole of our Ready to Wear collection all year round and develop a direct relationship with those customers”.

Service offerings for small and medium-sized retailers

As service offerings can serve as additional revenue streams for fashion retailers, they can be particularly helpful for small and medium-sized retailers. By providing services such as repairs, rental and upcycling, retailers can establish meaningful connections with their customers, especially within their local communities. This approach can act as an effective customer retention strategy, which is significantly more cost-effective than customer acquisition, and can therefore be particularly helpful for retailers with limited budgets. Furthermore, services allow retailers to have control over their products’ lifecycle, beyond the distribution stage, and through to the use and even disposal stages, which can enable them to build longer-lasting relationships with their customers.

Fanfare Label, a small sustainable denim brand, recently partnered with Liberty, a luxury department store, to offer a service called ‘Design your Own Jeans’. The service allows customers to either purchase a new pair of Fanfare Label jeans or bring in their own denim piece for customisation using off-cuts of Liberty fabrics. The service also includes a design consultation session with Fanfare Label designers to assist customers in designing and reimagining their pieces. Following the design session, skilled local artisans take over to bring the reimagined designs to life – which is the part of the service that customers would have to pay for.

From the retailers’ perspective, beyond its commercial and monetary aspects, the service represents a valuable opportunity to connect with customers, gain insights into their needs, foster deeper relationships, and ultimately cultivate brand loyalty. From the customers’ perspective, the appeal lies in owning a unique garment designed by them, or refreshing the look of a piece already owned, instead of buying an entirely new one. This can translate into the development of an emotional attachment to the product, encouraging them to take better care of it and to wear it for a longer period of time.

And to loop back around to the behaviour gap we talked about earlier – if customers could get a first-hand look into the time, effort, and resources that go into creating a single garment, their perceptions of the pieces they already own might gradually evolve, encouraging more conscious consumption in the future.

I believe that services can act as windows into the behind-the-scenes of fashion, whether that is through getting something repaired, upcycled, rented etc. They enable consumers to develop deeper relationships with garments and the brands behind them – a relationship that certainly does not exist in today’s throwaway culture, and one that has the potential to reframe and challenge the core relationship that people have with fashion.

While the impact and shift on consumer consumption habits would likely manifest as a long-term outcome, in the short-term, I believe that transitioning from a predominately product-based fashion industry to one that integrates products and service, has the potential to help fashion strike a balance between profitability and sustainability – which remains the industry’s primary point of tension.