Key Takeaways:

- SHEIN’s rapid growth and market dominance are fueled by their ability to quickly adapt to fashion trends, efficient shipping strategies, and low labor costs, but these practices raise ethical and regulatory concerns.

- The sustainability of SHEIN’s and Temu’s business models is questionable due to high cash burn, legal challenges, and potential regulatory changes, which could impact their future valuations and market positions.

- The overproduction rates and lack of transparency in the fashion industry highlight significant inefficiencies, with SHEIN claiming a lower overproduction rate compared to industry averages, yet overall environmental and ethical issues remain prevalent.

For years, Zara was the fashion king that reduced time to market to just one month (as opposed to the 12 month industry average). But there’s a new kid in town, SHEIN’s time to market is just 2 weeks – and SHEIN’s revenue is catching up to Zara’s. But SHEIN isn’t the only one coming for more established brands. Temu operates similarly to Shein, sourcing products directly from suppliers engaged in small-scale production runs, based on demand. Unlike Shein, which directly engages suppliers, Temu serves as an intermediary connecting suppliers to consumers. How are these (formerly) Chinese retailers changing the landscape of affordable fashion? And is their meteoric rise sustainable?

SHEIN is going public

While Temu is already publicly listed under PDD’s holding, SHEIN (now statutorily in Singapore) is amping up for its targeted $63 billion IPO. A monumental sum and an attractive prospect for the London Stock Exchange (especially with brands as Superdry are delisting).

What does the competitive landscape look like for affordable fashion right now?

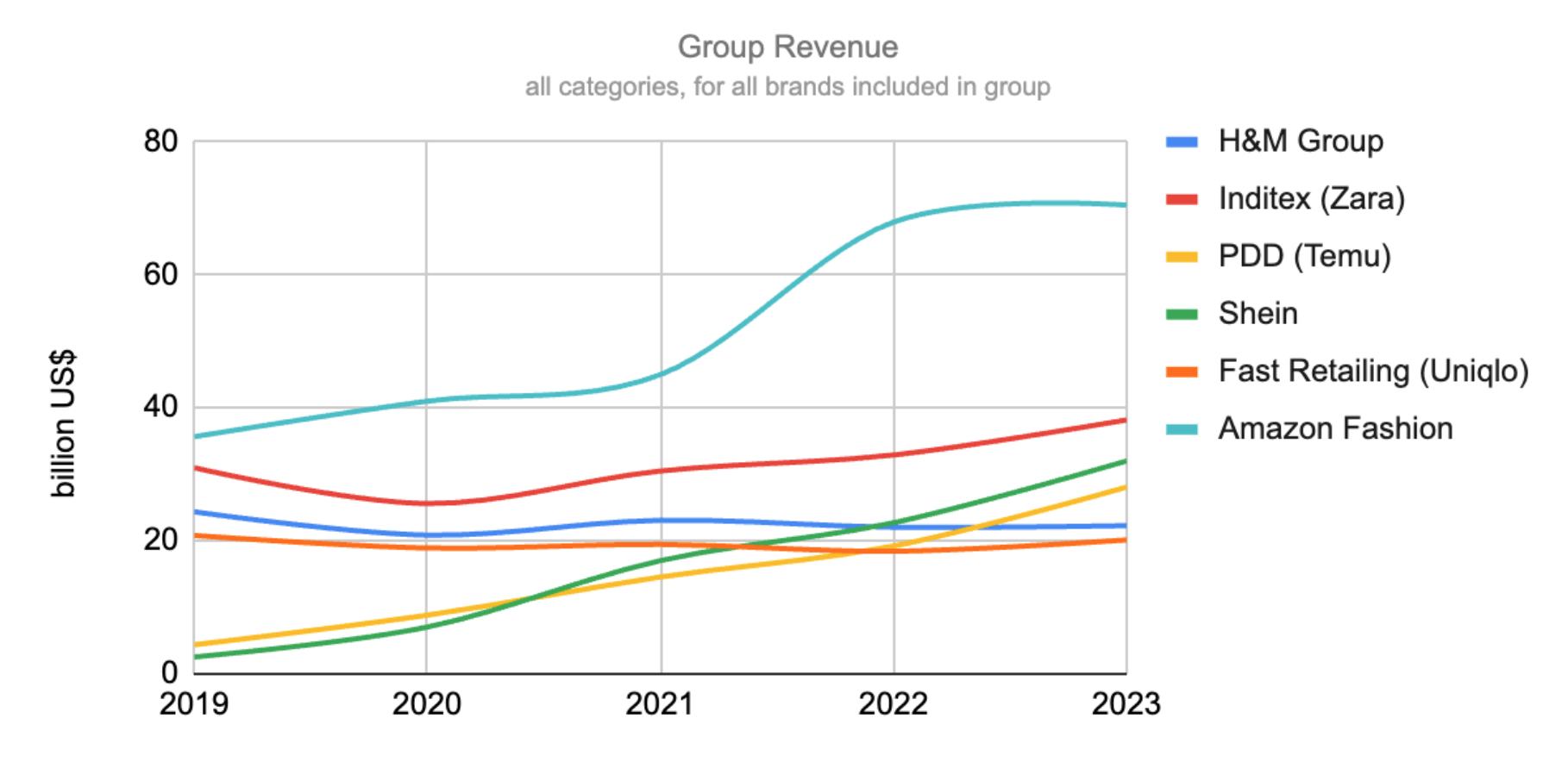

Chart 1: Group Revenue Retailers

* For Amazon, Amazon Clothes, Shoes, and Accessories revenue was used, not Amazon Group revenue. ** Please note that group revenue includes the revenue from all the brands under the group, across product categories (apparel, shoes, home goods) and across revenue streams (advertising and data monetization).

While Amazon’s Fashion revenue (albeit the highest of them all) is stabilising, SHEIN is quickly catching up to the more established brands, as is Temu. These retailers unfortunately don’t share any data on breakdowns of revenue streams, so it is difficult to assess what share of the revenue is attributable to apparel sales (both in units and dollars).

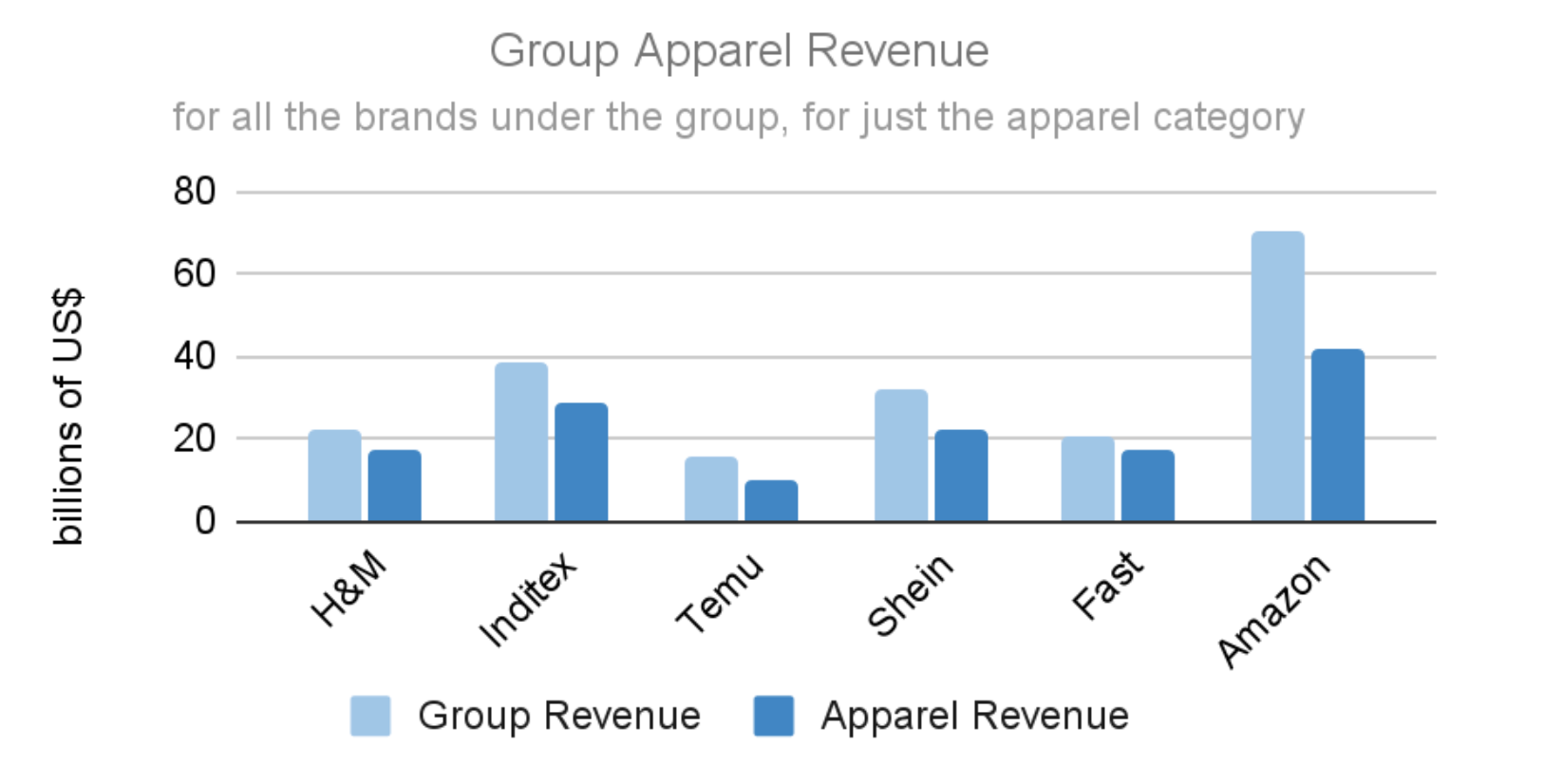

But In order to compare SHEIN to its competitors, we looked at the apparel category per group. Since brands often don’t disclose revenue breakdowns, we used assortment mix as a proxy for apparel revenue share. Revenue streams such as advertising and data monetization are not included in our revenue analysis, the apparel revenue could therefore be inflated.

Chart 2: Apparel Revenue largest fashion retailers

* For this analysis, Temu’s revenue was used, not PDD’s group revenue.

Chart 3 demonstrates that on average, around 70% of group revenue comes from apparel revenue. For fashion ecommerce at large, the apparel revenue share is 59%, accessories count for 24% and shoes for 16%.

What makes SHEIN so successful?

A quick recap on SHEIN’s dominance:

- React to trends in real time

SHEIN adds 7200 styles per day to their website to keep up with trends and they test these new styles in a matter of days, not months. Average time from design to production is 12 months in the fashion industry. For years, Zara was the pioneer that reduced time to market to just one month. But where Zara typically asks manufacturers to turn around minimum orders of 2,000 items in 30 days, Shein asks for as few as 100 products in as little as 10 days.

- Efficient Shipping Rates

Shein’s direct-to-customer (DTC) business model has thrived due to the trade policies of China and the US since 2018. That year, China began waiving export taxes for DTC companies after the US imposed additional tariffs on Chinese firms. Additionally, the US Trade Facilitation and Trade Enforcement Act of 2015 allows imports up to USD 800 per person to be duty-free. As a result, Shein and Temu have been exempt from export and import taxes since 2018. Temu manages shipping costs by prioritising sea freight over air freight, despite longer delivery times for customers. Temu takes a notable risk by using air freight for faster delivery, unlike AliExpress, which uses slower and cheaper sea freight. To mitigate these costs, Temu reportedly collaborates with J&T Express, an Indonesian logistics company seeking market share, which may be subsidizing shipping costs temporarily.

- Cheap Labour

Channel 4’s “Untold: Inside the Shein Machine” discovered workers who make clothing for Shein at factories in China frequently work 18 hours a day—with only one day off per month—for as little as 3 cents per hour. Garment workers are expected to produce 500 pieces of clothing per day. This allowed SHEIN to sell their garments for an average price of $14 in 2023.

SHEIN secret sauce has led to astronomical valuations over time:

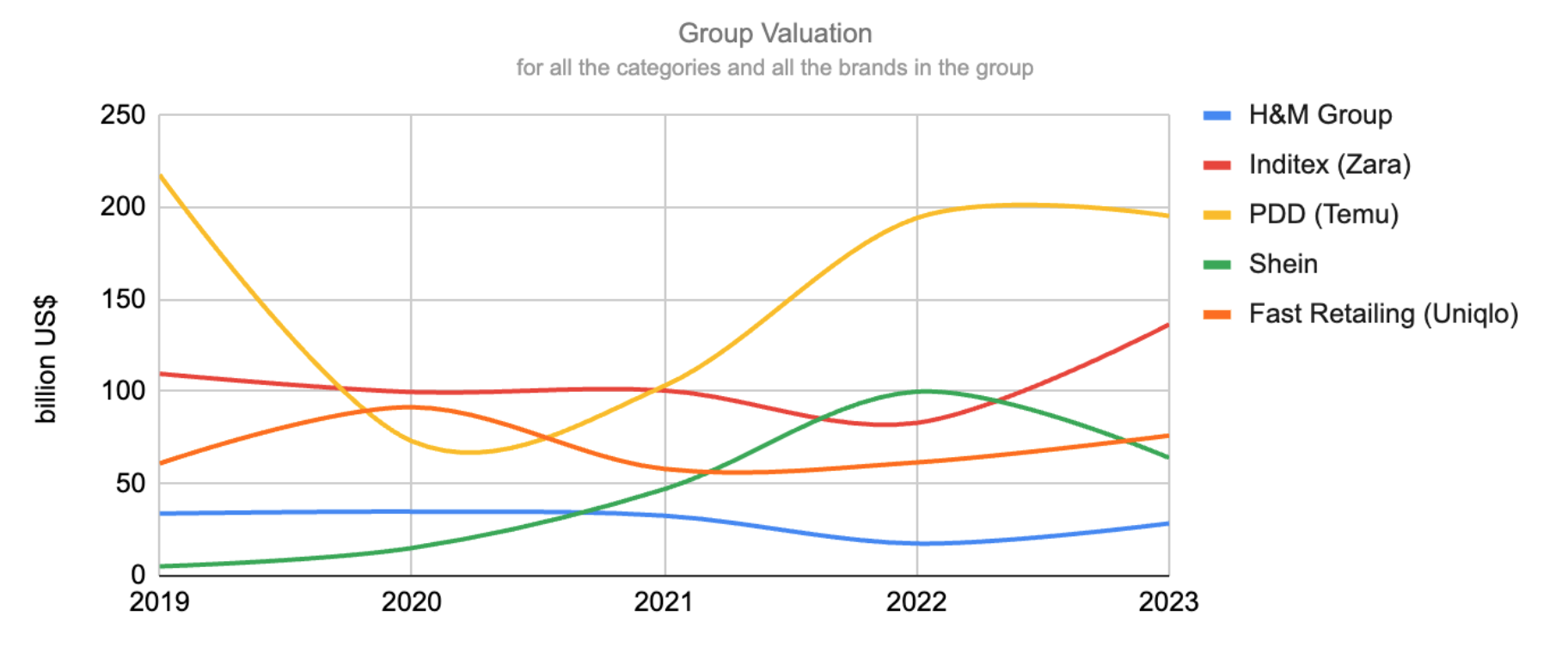

Chart 3: Valuation Comparison

* Valuation based on CompaniesMarketCap.com, except for SHEIN’s valuation (based on WSJ and Financial Times data). Amazon’s valuation was not included due to the wide variety in revenue streams.

Covid clearly impacted group valuations in 2020, but where H&M’s market cap has since taken a hit, Inditex’s market cap has been soaring. Shein went from a $100 billion valuation in 2022 to a $60 billion valuation in 2023. In a few months we’ll know if this number will rise or fall, but things are not looking up for SHEIN and its affordable fashion peers.

Is SHEIN’s success sustainable?

Cracks are starting to appear for the new giant. After struggling to get listed on the NY Stock Exchange, SHEIN is now looking to go across the pond. In preparation for their London Stock Exchange debut, SHEIN is trying to increase their valuation even further by increasing (potential) revenue.

The first part of this strategy includes increasing their price level. Edited (a retail intelligence company) has compared June 2023 prices to June 2024 prices and discovered that their prices have gone up between 15%-55% (depending on the category), surpassing ZARA and H&M price hikes. Whether customers will accept these higher prices remains to be seen, but if they do, it will likely increase SHEIN’s valuation even further.

The second part of this strategy includes selling their supply chain model to other fashion brands. SHEIN’s European peers have an average time to market of twelve months, a stark contrast to SHEIN’s one month, so they are probably eager to learn from SHEIN’s best practices. Which could be a very lucrative side hustle for SHEIN.

There are, however, huge caveats to this ‘supply chain as a service’ model. SHEIN’s crazy efficient supply chain works – for SHEIN. It might not be as useful for European retailers for several reasons:

- Nearshoring – A record number of US fashion companies have stopped listing China as their top supplier due to increasing diplomatic uncertainty and concerns about forced labour. Approximately 61% of apparel retail CEOs no longer use China as their primary supplier, up from 30% before the pandemic. Nearly 80% plan to further reduce sourcing from China over the next two years. These companies are primarily shifting to Vietnam, Bangladesh, and India, which offer large-scale production capacity and stable economic and political environments, according to the report. Data from China’s National Bureau of Statistics shows that garment production volume declined by 8.69% year-on-year. China’s apparel and accessories exports totaled $159.14 billion, a decrease of 7.8% year-on-year. SHEIN’s supply chain is based on its extensive network of 4,500 Chinese suppliers. If brands are moving away from China, using SHEIN’s Chinese manufacturers network could prove difficult to implement. However, as it stands, China is still the main supplier of garments globally, so it’s hard to say how big of an impact this trend will have.

- Impending Regulation

- Labour practices

Earlier this year, Shein attempted to go public on the NYSE but encountered obstacles due to SEC regulations concerning labour practices in some of their suppliers’ factories. “Shein previously aimed to list in New York City but was unsuccessful due to concerns over its unethical and irresponsible business practices,” Rubio wrote. “At the time, I alerted US securities regulators about Shein’s alleged use of slave labour and exploitation of trade loopholes. I now feel compelled to repeat these warnings and urge caution before the United Kingdom permits Shein to list in London.” It remains to be seen whether brands will want to partner with SHEIN’s manufacturing facilities.

- Advertising restraints

The bill would prohibit advertising for fast fashion brands and products, ‘similarly to how fossil fuel advertising was banned under the Climate and Resilience Law. France will apply criteria such as volumes of clothes produced and turnover speed of new collections in determining what constitutes fast fashion, according to the law’. A critical part of SHEIN success is acting on trends in real time. If other brands want to do the same, but can’t advertise it, it might be another part of the SHEIN model that can’t be copied.

- Design Infringement

SHEIN uses search engine data to see what’s selling, and then designs (sometimes entirely with AI) something very similar to that to sell. While effective, this is not always legal. There have been dozens of lawsuits over copyright infringement. While many affordable retailers react to trends in real time for ‘inspiration’, SHEIN is being sued over copying them. Other brands might not be able to copy styles the same way.

SHEIN, from a supply chain perspective, is no doubt in a league of its own. But in order to assess if it can capitalise on their supply chain as a service model abroad, a lot of questions need to be answered. And Shein isn’t answering any calls.

And then there’s the minor matter of formal approval. Beijing hasn’t officially approved SHEIN’s application to list outside of China, which they initiated last November.

How about SHEIN’s competitors?

Temu, meanwhile, is also facing uncertainty about its future valuation. While Temu’s aggressive strategy attracts a large number of users, there are serious concerns about the long-term sustainability of their model. Here’s why this approach might not be sustainable.

First of all, a high cash burn. Offering free expedited shipping via air freight likely costs Temu over $10 per order. Given their average order value, this amounts to billions of dollars annually to uphold their free shipping promise. Temu is reportedly losing an average of $30 per order as it aggressively attempts to penetrate the American market. Wish.com, with a similar story of aggressive marketing and extremely low prices, serves as a warning. After an initial surge in popularity, Wish.com struggled to retain customers due to low product quality. Their stock price plummeted when they had to cut back on marketing expenditures, demonstrating the pitfalls of unsustainable advertising practices. Despite the risks highlighted by Wish.com’s experience, Temu has some potential advantages that might help it avoid a similar fate. Unlike Wish.com, Temu has the financial support of PDD, a robust company with a $190 billion market cap. This backing allows Temu to potentially sustain its cash burn longer while building its user base.

Secondly, lawsuits over spyware. The rivalry between the United States and China in the e-commerce sector has fostered deep distrust, which has intensified since Pinduoduo, a Chinese sister company of Temu, was removed from Google’s app store due to “malware” concerns. Pinduoduo was suspended after malware was discovered exploiting specific vulnerabilities in devices commonly used in China, such as those from Xiaomi, Vivo, Oppo, and Samsung. The malware allegedly bypassed user security permissions, accessed data from other apps, and prevented uninstallation. ‘Despite the company’s denial of these claims, Kevin Reed, Chief Information Security Officer at cybersecurity firm Acronis, reported that Pinduoduo requested 83 permissions to access biometric data and information via Wi-Fi networks and Bluetooth. Lawmakers continue to warn against using Chinese-owned apps due to potential data privacy breaches or interference from the Chinese government, although there is no direct evidence supporting these claims’.

How efficient is SHEIN as compared to their competitors?

And then there’s the actual efficacy of their supply chain. While it all sounds glorious from a financial perspective, we don’t actually know what’s going on. How many garments do these brands produce per year? How many remain unsold? What happens with these unsold garments? Their actual efficacy remains unknown, because disclosing (over)production volumes is not yet subject to regulation.

According to various sources, SHEIN produces roughly 1.2 million garments per day. Assuming a five day work week, that’s 324 million garments per year. With a turnover of 45 billion, that would come to roughly 139 dollar price tag per garment. Which is not adding up.

However, based on what we do know – revenue and average prices – we can estimate (over)production volumes of the major players in affordable fashion.

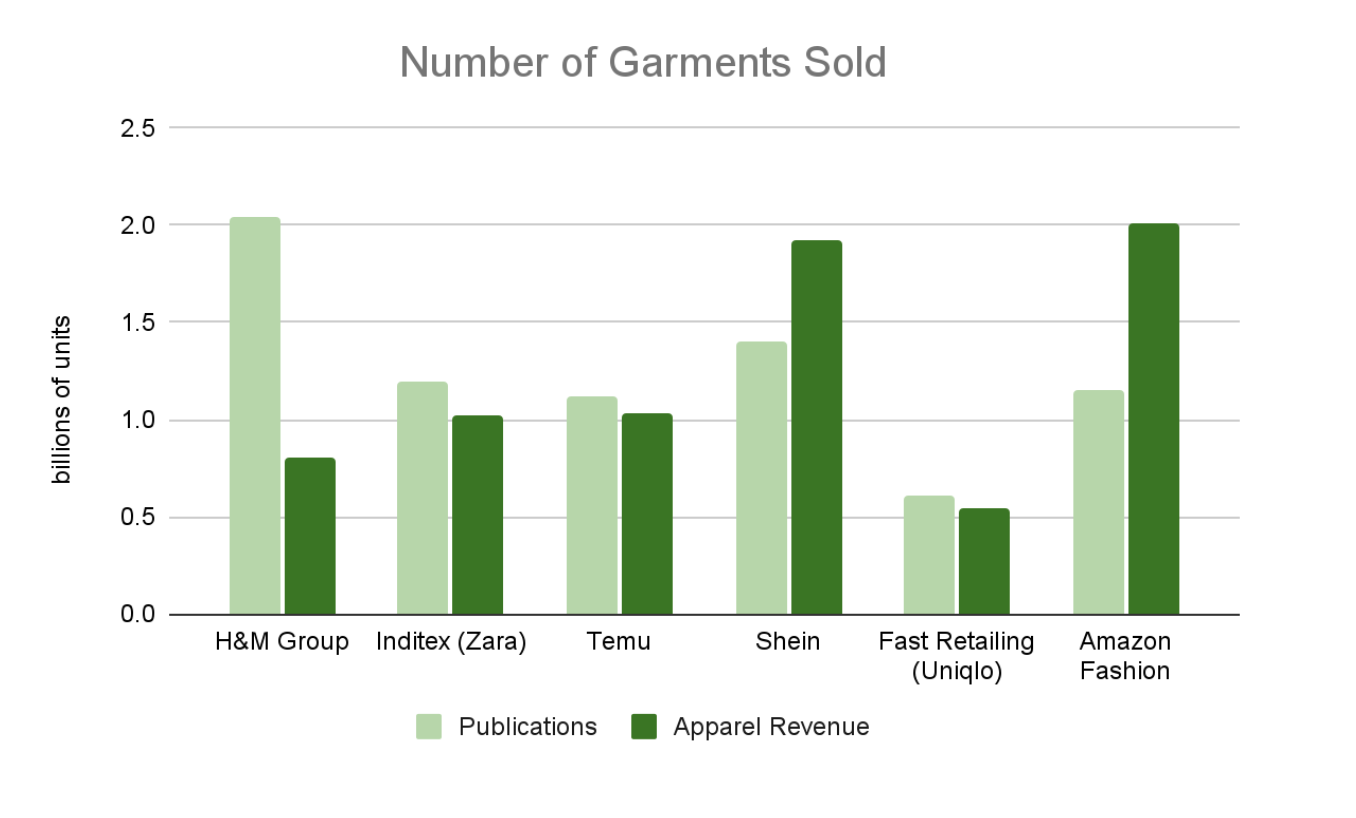

Chart 4: Units Sold per Group in 2023

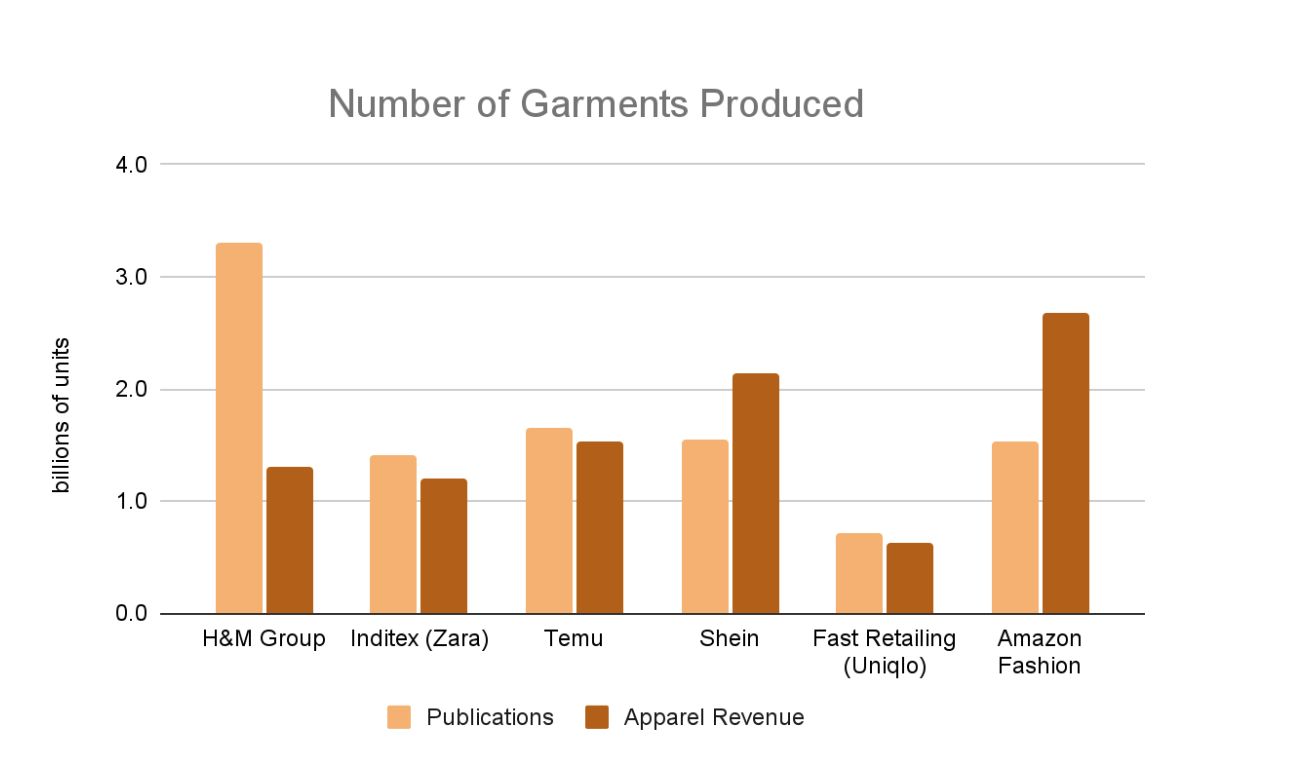

Chart 5: Units Produced per Group in 2023

We compared units sold based on average price (based on average SKU price online) and apparel revenue (based on assortment mix) for the whole groups, with units sold based on published (company) data on either sales- or production volume. This is a rough estimation method, since average price available does not equate average price of garments sold, and share of assortment available does not equate share of assortment sold, but it’s the best we’ve got at this point.

Overproduction rates are based on publications and best guesses. On average, brands overproduce at a rate of 30%. As per Tech Tailors Overproduction report, that number is most probably closer to 38%. According to the SHEIN executives, their overproduction rate is just 10%. According to various sources, Zara’s overproduction rate is 15%, still significantly lower than the industry average.

In 2018, the New York Times reported that the H&M group sold 3 billion garments that year. If we look at the revenue change from 2018 to 2023 and correct for inflation, total units sold in 2023 would amount to roughly 2 billion. If we use revenue data and average prices, units sold in 2023 would be 0.8 billion. That’s a significant gap.

According to the Business of Fashion, Inditex produced 934 million garments in 2015. If we look at the revenue change from 2015 to 2023 and correct for inflation, total units produced in 2023 would amount to roughly 1.4 billion. Based on revenue data, units produced in 2023 would come to 1.2 billion. Which, with the margin of error in these calculations, is roughly the same.

When we look at SHEIN’s apparel and average SKU price of $14 in 2023, we estimate that SHEIN sells 1.9 billion garments per year. According to SimilarWeb (a retail intelligence platform) in 2021, 100 million units per month were sold, If we account for an apparel revenue share of 70% and take the growth rate in revenue between 2021 and 2023 (and correct for inflation), that would amount to 1.4 billion garments sold based on SimilarWeb data. That’s a 500 million garments gap.

While unit data on Temu sales- or production volumes is scarce, we do know how much they ship globally as compared to Shein, 20% less. It is therefore estimated that based on logistics data, Temu sells 1.1 billion garments per year. Based on revenue data, we estimate that Temu sells 1 billion garments per year. That’s pretty close. It is important to note that Temu is a market place, more than an actual manufacturer. So strictly speaking, Temu doesn’t produce any garments themselves.

Uniquely so, Fast Retailing (holding group of amongst others Uniqlo) reported it produced 600 million garments in 2023. Since Uniqlo revenue contributes to 84% of the group revenue, we used this information to estimate the group production volume, which is estimated at 700 million units. Which is (in an absolute sense) close to the 600 million units we estimated based on revenue.

Finally, Amazon. We should note first that we used the revenue stream Apparel, Shoes and Accessories as an indicator for apparel revenue. Amazon doesn’t publish data on revenue breakdown, so we used several different sources to estimate its apparel revenue. Reality could be quite different, we won’t know until Amazon releases data themselves. Jeff Bezos did, however, release that in 2020, 9% of sales in this category were from private label brands, the remaining 91% were from third party brands. Meaning these brands technically produce the clothes, not Amazon. According to SimilarWeb, Clothing, Shoes, & Jewelry generated 118 million in unit sales and $3.0 billion in revenue in June 2021. If we look at the revenue change from 2021 to 2023 and correct for inflation, total units sold in 2023 would amount to roughly 1.1 billion. Based on revenue and average SKU, units sold are estimated at 2 billion. Almost a factor two higher.

All in all, these brands together sell roughly 7-8 billion garments per year and produce roughly 9-10 billion garments per year. Again, these are very rough estimates that should be taken with a grain of salt, but it also serves as a benchmark for sources claiming that these brands are producing in the millions, where in reality, it’s in the billions.

The greater fashion industry would benefit from more regulation centred on production volume and weight. So much data in this industry is focussed on value, that we don’t know how much is being (over)produced. It’s time to move from financial economics to unit economics, so we can get a clearer picture of who is actually overproducing. Luckily, that’s just around the corner.

Impending legislation for all fast fashion brands

More regulation is coming in to threaten the business model of both established and new affordable fashion brands’ valuation:

- Ban on destruction of unsold clothes – ‘Economic operators that destroy unsold goods would have to report annually the quantities of products they discarded as well as their reasons why. Negotiators agreed to specifically ban the destruction of unsold apparel, clothing accessories and footwear, two years after the entry into force of the law (six years for medium-sized enterprises)’. Meaning getting rid of unsold inventory will become more difficult, and more expensive.

- Fee per garment sold – ‘A surcharge linked to fast fashion’s ecological footprint of €5 (£4.20) an item is planned from next year, rising to €10 by 2030. The charge cannot, however, exceed 50% of an item’s price tag.Violland said the proceeds from the charge would be used to subsidise producers of sustainable clothes, allowing them to compete more easily’. This would mean a price spike for all fast fashion players, one that consumers might not be willing to pay.

- Custom Regulations – The US Congress is working on legislation that would close the customs evasion loophole, and Rubio urged the UK to take similar action. Custom fees are bound to go up, meaning a price increase for SHEIN and Temu customers.

These regulations will undoubtedly give us more insight in the sales and overproduction volumes of brands. But more importantly, they will force brands to reevaluate critical parts of their business model. Perhaps it’s time for brands to stop optimising inherently limited existing supply chains, and start (re)building new ones instead.