Key Takeaways:

- OpenAI adding ads to ChatGPT has been a headline-grabber, but the real picture is one of economic necessity more than new market opportunity and invention: the company’s costs continue to massively outpace its revenue. And building a complete ad tech stack, and growing a market to match, would be a significant struggle even if its direct competition didn’t already hold a monopoly on that market.

- Today, as well as controlling the AI model and application considered state of the art for most everyday use cases, Google owns the entire programmatic ad stack (covering 90% of internet inventory) and has the luxury of subsidising Gemini almost indefinitely. Disruption here is more likely to come from publisher lawsuits – many filed this month – rather than direct competition.

- Fashion brands should watch and wait: as appealing as the idea of showing up in high-intent conversations for an audience of 760 million people is, the real race to integrate advertising into AI isn’t going to come until the switch is flicked for Gemini.

Summarise and debate with AI:

Take the content and context of this article into a new, private debate with your AI chatbot of choice, as a prompt for your own thinking. (Requires an active account for ChatGPT or Claude. The Interline has no visibility into your conversations. AI can make mistakes.)

As you’ve probably noticed, there sure are a lot of adverts on the internet. But as a raft of lawsuits from major publishers this week evidence, there’s really only one company controlling the liquid inventory, the exchange, and the auction markets that run the web advertising economy from behind the curtain.

At the risk of spending two consecutive weeks’ worth of analysis on one business, Google (the all-encompassing ad giant in question) is the real force behind the headlines again – even though you wouldn’t think it based on how many column inches are being dedicated to its primary opponent in the AI chatbot space.

Let’s not get ahead of ourselves. What’s actually happened this week?

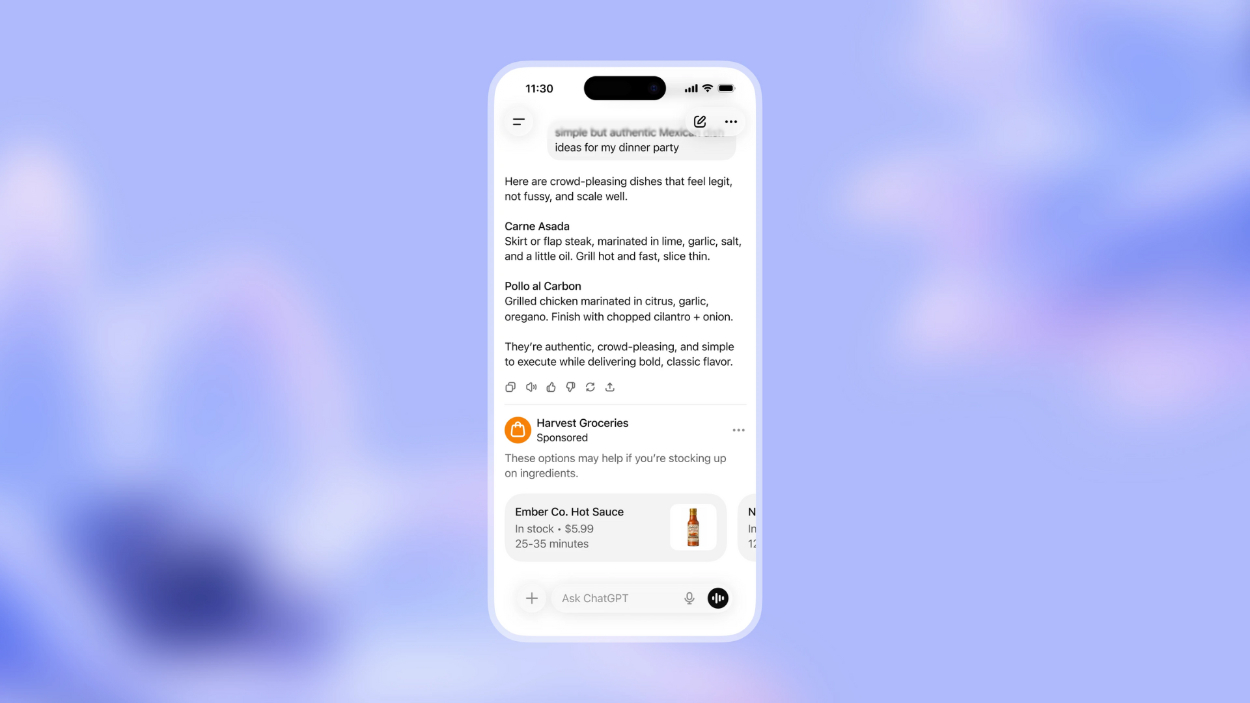

“Ads are now in ChatGPT!” is both an authentic and accurate statement on the week’s happenings: OpenAI has indeed added advertising into one of the world’s most popular consumer apps, on its free and lowest monetised pricing tiers. This is proving to be something of a wake-up call for the gigantic userbase that has, up until now, flocked to AI because it was free to use.

Before you read on...

Our weekly news analysis will always be available to read here at The Interline, but you can get it (along with notifications for new podcast episodes, events, and more) in your inbox by signing up to our mailing list.

Before we get into why this all matters for fashion and beauty companies, though, it’s worth rehearsing the economics of AI chat apps in general.

To carry on training massive new models that continue to push the state of the art in text, image, video, and audio generation, research labs like OpenAI have to spend gigantic amounts of money on compute and energy. For every AI lab bar one (Google again!) external investment is the only way to find that money, which makes model creation a losing exercise by definition.

Once those models are trained, the intention is then to recoup some of that cost, and to fund some of the next cycle, by licensing those pretrained models to developers and B2B partners, and by attempting to encourage mass market consumers to also directly pay to use them by implementing daily limits and gating newer models, capabilities, and extensions behind a paywall.

That last challenge is the point at issue for our purposes this week, because it has largely failed to convert users into subscribers.

Of the 800 million individual users that OpenAI boasts about, only around 5% are paying to use the application. That wouldn’t be a gigantic problem if, as is the case with plenty of other SaaS products, the paying users covered the cost of the free ones. For a range of different reasons, that doesn’t pan out for pure-play generative AI companies.

Observe: while OpenAI’s revenue surpassed expectations for the full 2025 calendar year (hitting $20bn USD rather than the expected $13bn, as announced last week), making it a wildly successful company on the surface, its costs far outstrip its income.

Irrespective of what you like about using AI, there is simply no long-term business model in indefinitely subsidising a product whose R&D budget eclipses its runtime revenue unless you have waterfalls of cash flowing in from somewhere else.

Inference for language models (the process that happens when you submit a query) does become cheaper over time, which closes that gap between cost and revenue to some extent, but this only holds true for extant models that undergo a post-training process of optimisation or, more likely, get quietly quantized and context-window-shrunk until users begin to notice. And even “free” customers will churn if they’re kept behind the new model frontier for too long.

As OpenAI themselves say, “The cycle compounds”. They mean it in the opposite sense, of course, but it’s very easy to read it as a self-reinforcing downward spiral. Users want new AI models and features that are staggeringly expensive to create and then costly to service for the initial stage of their lifespan, only becoming potentially profitable-per-query once they’re sufficiently optimised to no longer be considered “SOTA” (state of the art). Sunrise, sunset.

So what’s an AI lab to do, before analysts predict it might just run out of money?

To cut a messy story short, consumer AI companies have two options. They can either swallow that ongoing capital and operational cost if they have other business units to offset it (we’ll return to the one company that can do this in just a second) or they can find alternative ways to extract value from the users who interact with their models and, by dint of their volume, help sustain the company’s valuation, but who are intransigent about opening their wallets.

And the most road-tested, investor-accepted spigot a company in that second situation can turn is to put advertisements in the product – either on an affiliate basis (where the company exerts a toll for directing high-intent transactional traffic) or as a way to build out an ad economy of its own, and to offer query or topic-based placements to bidders in a supply-demand mapping market like the one that runs the money inside the web.

For end users, an ad is an ad. People care about relevance and annoyance, and the populace at large has been pretty well conditioned to understand why ads need to exist, and to make reasonably informed choices about the value exchange of clicking on them.

From that point of view, the insertion of ads in a dedicated area at the bottom of the ChatGPT window is nothing new. We’ve been stuffing ads into consumer applications – especially on mobile – for a long time, and sponsors and users have reached something of a detente where the model kind of works for everyone.

End users don’t care if that ad came from a direct negotiation between platform and sponsor, or whether it came from automatic bids, made on an impression-based exchange where inventory moves around in micro-seconds.

Advertisers, though, care very much about that distinction. Because the prevailing ad model is both a perfect flywheel, pairing supply and demand at an extremely granular level, in the most relevant situations possible… and also a source of immense ongoing animus towards the one company – Google! – that controls the entire advertising technology stack.

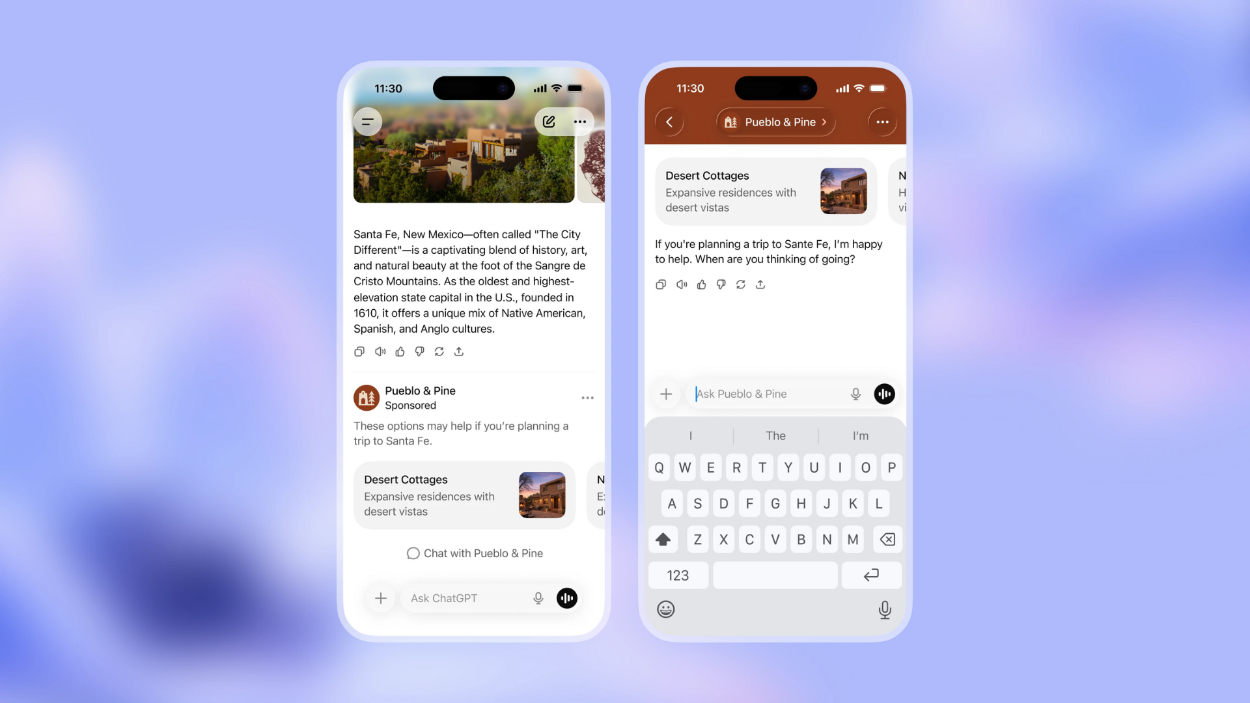

Right now, it’s not clear how OpenAI is serving ads and managing the market for them. Its announcement post says that it plans to “test” ads “when there’s a relevant sponsored product or service based on your current conversation,” which, to advertisers, should read like the perfect next step in pairing intent with inventory, because AI queries are perhaps the highest-intent signal there is.

But as promising as that level of relevance sounds, especially when you pair it to the 95% of OpenAI’s userbase that are now in-scope for being shown ads (around 760 million active users) there’s a gigantic gulf between saying you have a new surface to show ads, and actually building an ad tech ecosystem and an economy from a cold start.

Especially when the current ad tech stack, and the massive market built around, is all owned by Google.

Today, advertising markets are based on the understanding that there’s a liquid, high-speed system to match advertiser demand to publisher supply, and to provide the frameworks for mapping budgets and bids to performance metrics and events. Behind that, you also need systems to serve the ads when they need to be shown, and the exchange to run the auctions.

In all these areas, Google is the only game in town. Under its Google Marketing Platform, it owns DV360 – a platform for managing programmatic media buys across a wide range of formats including display, video, audio, and TV, but that crucially covers more than 90% of the internet – the AdX clearing house, and Google Ad Manager, which is the successor to the tool that older publishers (of which we have at least one at The Interline) will know as DoubleClick.

And of course, it also owns Gemini, which is rapidly becoming the AI app to beat.

That monolithic stack is also under constant criticism for, well, being monolithic. It was officially designated a monopoly for precisely this in a case brought by the US Department of Justice in 2023, which reached a judgment in April of 2025.

And this week a slate of different publishers followed up on that ruling by filing suits alleging that Google’s stranglehold on the ad tech stack, and on the market it rules, had purposefully deflated prices and reduced publishers’ ability to make money.

These fillings are not claiming that Google has a bit too much power. They’re claiming that there is simply no central advertising market that can exist without Google’s say-so.

Which is interesting context when we consider that, just two days ago, the Co-Founder and CEO of Google Deepmind – speaking at the World Economic Forum in Davos – said that the company has no plans to insert ads into Gemini, and that he believes that OpenAI has jumped the gun on adding them to its product.

A cynic would say that Google is just biding its time, and that it’s inevitable that Gemini will include similar ads as it follows its trajectory towards becoming a viable eCommerce platform in its own right. A realist will point out that Google’s doesn’t need to insert banners into Gemini, since it’s already capable of amortising user costs across other areas of its business, as well as simply directing people to the places that the planet’s biggest (really only) digital advertising business already touches.

Which should give you some idea of the uphill challenge that OpenAI now faces. From a cold start, the company needs to rapidly stand up and scale an advertising economy that can compete with one of the most entrenched systems in the world – all at the same time as experimenting with other ideas in health, wearables, and more, and all without having any direct ownership or control of the channels that ads will direct shoppers towards.

And to underline just how entrenched the competition is when we broaden our lens beyond the West, this week also saw China’s Alibaba linking its AI app (and the titular model underneath it) Qwen, which itself has more than 100 million users, directly with its Taobao online shopping platform, its Alipay payments backend, and also its travel-booking platform Fliggy. While there are no direct analogues to this kind of super-app ecosystem in the US or Europe, it should be immediately obvious that OpenAI simply doesn’t have the levers it will need to pull to kickstart an ad market without the direct support of big-box partners.

For fashion and beauty brands, this week’s news does provide some foundation for optimism that there could be a genuinely greenfield advertising market opening up. But for all the attention that’s being sent its way, The Interline thinks it’s unlikely that OpenAI inserting ads into ChatGPT will be the wedge that manages to disrupt an advertising market where the rules have been extremely fixed for a long time.

Slower-moving legal cogs might lead to that disruption, but for the time being we would encourage readers to keep an eye on advertising in AI, but not to jump in too enthusiastically… at least until Google decides to flick the switch in Gemini.