Key Takeaways:

- This week saw the tech hype cycle in overdrive – especially where the far-flung concepts of space-based data centres and sentient AI models running their own social networks were concerned. There is a lot of cool water to pour on these ideas, and while they are interesting to analyse in industry context, their effects on fashion’s relationship with AI are going to remain limited.

- Anthropic chose to unveil the latest point model in the Claude Opus series with a demo that captures an odd (and amusing) angle on the footwear development lifecycle, and reminds us that big AI labs are still trying to map general purpose AI to very specific use cases.

- The announcement that a prominent luxury brand found non-compliance in fully a quarter of its audited supplier base puts all of the above into context, reinforcing the long-standing mandate for fashion to address the systemic failings in its own supply chains before it looks too far ahead.

Before you read on...

Our weekly news analysis will always be available to read here at The Interline, but you can get it (along with notifications for new podcast episodes, events, and more) in your inbox by signing up to our mailing list.

There are weeks where the team at The Interline feels some tension between our status as tech media, and our place as a fashion publication. It can be tricky to decide which of those angles requires the most focus, because there aren’t always obvious handholds where they converge.

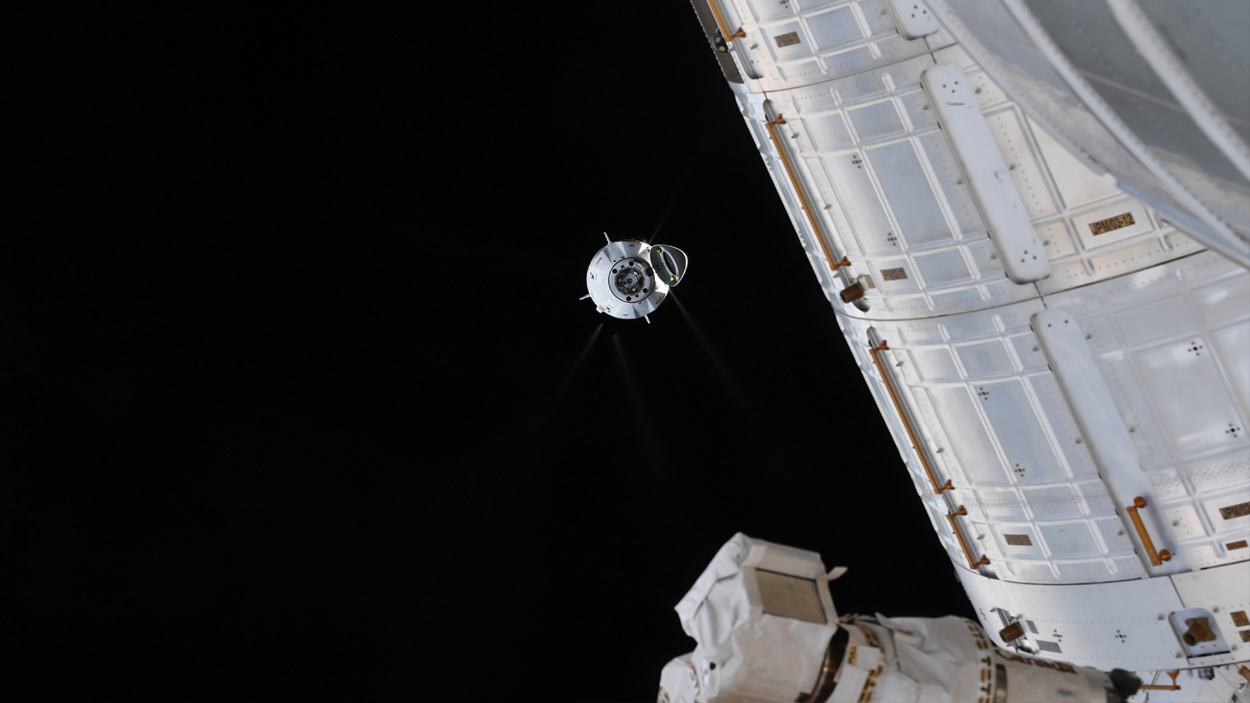

On the face of things, you’d expect this to be one of those weeks where tech won out: the trade media is filled with talk about the SpaceX merger with xAI, this was the week that people went truly nuts over a “social network” built by AI, for AI, and a new frontier model launched with a demo video that seems tailor-made to make overstretched product development professionals laugh (or cry).

But at the same time, this week also saw something resurface – even if it went under-acknowledged – that reminds us of the large-scale systemic that challenges remain in the fashion supply chain, whose impacts are far more present and tangible than far-off flights of tech fancy.

Speaking of which, it feels like the hype around AI-infrastructure-building is really relieving people of some of their senses, as well as investors of their usual due diligence.

The left-pocket-to-right-pocket “acquisition” of Elon Musk’s xAI (which also owns X, the social network that used to be Twitter) by Elon Musk’s SpaceX is momentous in that it apparently creates the most valuable private company in history. And anything promising a new frontier (literally in this case!) for AI is worth consideration, given how much 2026 is looking like the year that the practical impact of generative artificial intelligence picks up.

In practice, though, the intent behind this move feels pretty shady, the science of whacking data centres in orbit is even less certain, and the underlying demand might not even be there at all.

Moving debt load, losses, and liability between companies with very divergent financial outlooks isn’t a new big-money strategy, but it’s a particularly brazen one in this case. xAI lost more than $1.4 billion in the most recent quarter on record, and raised an additional $20 billion investment last month. There’s not a lot of in-flow there.

By contrast, SpaceX is cashflow-positive in a pretty major way, making more than $8 billion in profit last year, and holding onto extremely lucrative government contracts thanks to the lamentable way American orbital launches have been left almost exclusively to the private sector. But with SpaceX gearing up for an IPO that direct advisors are calling a chance to bet on “the most ambitious, vertically-integrated innovation engine on Earth,” a more cynical read might be that there’s a small opportunity window to financially-engineer a money-losing company, in a money-burning sector, onto the balance sheets of a business with an expected post-IPO pop, transferring some of that in-the-red yoke onto retail investors’ shoulders.

Then there’s the question of why we apparently want to put data centres in space (one of the primary stated aims of this acquisition) in the first place.

Clearly the energy demands of earth-bound data centre usage, thanks to the boom of AI, are high. And clearly companies are pouring a lot of capital into building those data centres – with the biggest tech companies all ploughing hundreds of billions per year into direct and orthogonally-related projects.

But the costs of launching those structures into space instead, and then maintaining them when they’re up there, are stratospheric. Sure, it’s more efficient to collect solar energy without an atmosphere in the way, and the energy needed to cool an orbiting data centre is theoretically far lower with a passive, radiative heat-dispersal model than an active one, running on fans, water pipes, and heat exchangers, here on the ground. But the engineering challenge of building that sufficiently huge dispersal surface, and the logistics, costs, and fuel use involved in getting all the constituent parts out of the gravity well is gigantic.

And what are we even putting in those data centres? GPUs that are expected to burn out after a few years? We suppose the contracts to keep bringing them back down to earth and putting new ones up there will be lucrative, at least.

To top it all off, as Techcrunch pointed out yesterday, it’s not exactly clear that demand for on-planet data centres (which is a phrase we never thought we’d end up writing) is actually going to outstrip the tremendous amount of new supply we’re already building.

The investment flowing into building out data centre capacity is predicated on the bet that AI usage is going to increase dramatically. According to analysts with better data than The Interline has to hand, data centre capacity is already set to double over the next four years with the build-outs that are already in-scope, and by the end of that same 2030 horizon, AI is expected to account for 50% of all data centre workloads – up from 25% based on today’s usage and capacity.

That’s a 4X increase in the amount of compute being assigned to AI, which would require the need for inference to shoot up from what, today, already feels like quite a ubiquitous roll-out.

Looking within fashion and beauty’s walls, do we see anyone who’s not at least playing around with AI today? Do we realistically expect four times more people to be doing it by 2030, or at least quadrupling their query volume if nobody else gets onboarded?

To put that increase into context, a 4X increase in the user counts of the major consumer AI apps would mean OpenAI’s userbase going from 800 million to 3.2 billion in four years, and Google’s Gemini userbase increasing from 700 million to around 2.8 billion. Combined, that would mean the majority of the world’s population would be using AI every week.

We’re drifting (forgive the pun) a long way from fashion applications here, but the reality is that our industry is already placing what we consider to be a reasonable amount of demand on AI workloads. That will definitely scale up over time, but those predictions seem optimistic based on the adoption and diffusion curve we see today.

And, going back to the news for a moment, if we’re only dubiously on-track to need exponentially more AI capacity in the next few years, and that capacity is already being built on earth, should we be putting any stock in transferring that capacity to space?

Fashion’s primary concerns, when it comes to AI adoption, are creative and environmental. We’ll park the former for another time (although our DPC Report 2026 has some essential reading there) but the sustainability impact of AI training and inference has become one of the industry’s primary concerns, and is the counterpoint that comes up the most often in presentations, panels, and debates about how brands with public sustainability commitment should be deploying AI.

We have an op-ed coming on Monday that documents the scale of fashion’s water “bankruptcy” that’s based primarily on actual clothing production, so if we add data centre water-use to the mix as well – and if we remind ourselves that human-centric climate change is already challenging fashion’s supply chains – it might feel like moving that impact off-world could be a net positive, but that would be ignoring the resource-intensive work of actually getting data centres up there.

All of which is a very roundabout way of saying that The Interline wouldn’t bet on space-based data centres doing anything to move the needle on how fashion thinks about AI. We might get some more cool spacesuits out of the deal, though.

Still on the AI hyper subject, this was also the week that the internet lost its collective mind over what’s now known as OpenClaw, but was very recently called ClawdBot or MoltBolt. Billed as “the AI that actually does things” OpenClaw would be more accurately described as a way of deploying existing models that allows them to hook into a range of other services – both on-device and in the cloud.

There’s nothing fundamentally new about that concept that isn’t already covered by existing approaches to agents and agent swarms, or by MCP, but the furore was sparked by three other pieces: the fact that OpenClaw can route queries and responses through the messaging apps that people already use (WhatsApp, Telegram, Discord etc.) which does, in-use, feel like a bit of a change in how we interact with AI; the fact that these are models with good coding capabilities that, given filesystem access, can build extensions for their own environments and new applications; and the fact that those things culminated in the creation of MoltBook, or a social network coded by AI, with AI-only posters.

The latter is a novel social experiment, but you only need to glance at the feed of new posts to see an AI-written dirge about NFTs to understand that something being architecturally interesting doesn’t automatically give it interesting content. There’s a lot to say about how AI writes, and what it writes, but The Interline continues to remind readers that language is not the same thing as intelligence – and for fashion’s purposes, this should serve as a reminder that confident output from AI models, even the ones trained on fashion-specific data, should not become the foundation for blind trust.

More interesting, in a gloomily funny kind of way, was this week’s unveiling of Claude Opus 4.6. A new point release in an AI model family isn’t normally something we’d cover, but the video announcement of its “everyday work” capabilities zeroes in on something that will make some of our readers shudder: a folder full of spreadsheets containing BOMs, production plans, and other product data pertaining to the launch of an Olympic running shoe.

On the one hand, it’s interesting to see such a prominent display of AI applications in the everyday work of fashion and footwear, but watching that video, The Interline felt as though we could hear the collective sighs of a generation of PLM builders and users. (Although if anyone reading this is actually developing and costing a new footwear platform with just a chatbot and a folder of disconnected Excel files, know that our thoughts are with you.)

Behind the comedy potential of that video, though, is a very serious concern about the way AI is flattening (or even demolishing) the delineation lines between software categories, and challenging the valuations of enterprise software companies. This, in fact, will be one of the key themes of The Interline’s AI Report 2026, coming this spring.

But behind the swirling fog of all those slightly silly stories came much more sober reporting that Prada has completed a multi-year supply chain audit, and found that 25% of the partners it inspected had breached the luxury brand’s compliance standards, specifically where labour is concerned.

We’d encourage readers to let that one sink in, and then to contrast it against far-flung ideas like sentient AI models on social networks, and data centres whipping around above the world. It’s problematic to do direct extrapolation from this kind of work, but it’s not a huge logical leap (especially when you have some insider knowledge, as The Interline does) to guess that, if a quarter of the suppliers that get audited are non-compliant, then a similar proportion of the suppliers that didn’t get audited will fall into the same bracket.

This is, not to put too fine a point on it, a symptom of a serious, multi-decade, systematic issue. Fashion (not so much beauty) has long been able to handwave away allegations of environmental and ethical abuses on the grounds of a lack of knowledge: what the industry didn’t know, it didn’t need to disclose. And while the regulatory net that was due to tighten around the sector has picked up its share of holes, consumer and government / NGO demand for transparency is still on the rise.

The Interline has written extensively before about the under-acknowledged plight of garment workers, in perspectives from both staff and contributors, with the latter capturing the problem pretty succinctly: human rights are not advancing meaningfully enough when those rights remain in the hands of the private sector. And this will remain true if that private sector becomes to distracted by technology hype and looks more to the stars than at the people on the ground.

This is, we realise, a technology publication for fashion. And there’s no question that there was a lot to analyse (or dismantle) in tech this week, but for the nth time over the six years we’ve been doing this, we’re reminded again that there is so much still to solve about how fashion operates today.

And yes, there will, no doubt, be AI solutions promised to tackle the persistent problem of upstream invisibility, but those solutions will still need political and real capital to deploy, so our continued hope is that at least some of the spending earmarked for bleeding-edge AI initiatives goes to improving endemic challenges upstream.