Released in The Interline’s DPC Report 2026, this executive interview is one of an eight-part series that sees The Interline quiz executives from major DPC companies on the evolution of 3D and digital product creation tools and workflows, and ask their opinions on what the future holds for the the extended possibilities of digital assets.

For more on digital product creation in fashion, download the full DPC Report 2026 completely free of charge and ungated.

For a while now the broad shape and scope of 3D and DPC strategies have been generally accepted, but now companies are asking some fundamental questions about how far those initiatives should stretch. Some see a clear opportunity to take them further. Others potentially see arguments for either ringfencing them where they stand, or possibly even scaling them back. Technology footprints will always morph over time, but this feels like a deviation from the standard. What’s your perspective?

Digital Product Creation has taken many shapes over the last decade, but the long term value of these programs, and their ability to last, depends entirely on how they were defined at the start. If you define DPC as a technology program, it may eventually stall. If you define it as a business model shift, it will continue to evolve and flourish.

Guy Kawasaki tells a cautionary story from the early ice industry. Ice harvesters defined their businesses as cutting blocks of ice from frozen lakes. Ice factories defined their businesses as freezing ice in buildings and delivering it. Both models, and the companies behind them, died because they defined their work by the method rather than the value. The true consumer benefit, as Kawasaki put it, was cleanliness and convenience.

DPC has the same vulnerability. When it is defined by a specific tool or workflow, it will always be limited by that tool.

Consider Company ABC. Their goal is to reduce sample costs through 3D prototyping. They select a tool, train their team, and expect quick wins. The team struggles with complexity and merchandisers cannot easily review digital samples. Even though physical samples are reduced, leadership does not see enough value to justify continued investment. The project ends.

Company XYZ begins with a different definition. Leadership wants faster decisions, more relevant product, better forecasting, and less financial strain from excess inventory and carrying costs. They build an agile go to market model centered on detailed consumer insights, shared product data, fast and inexpensive sampling, and accurate visual decision making. The goal is outcomes, not tools. It just so happens that 3D digital sampling and AI assisted insights provide the best results for the job.

Because the strategy is defined around business value and process, new technologies fold in naturally. When a generative AI design capability emerges that dramatically speeds concepting and aids decision making, their teams adopt it quickly. It aligns with the process rather than forcing a new strategy.

Executives do not fixate on individual technologies. They care about profitable growth, compelling product, and the speed to make accurate decisions. DPC thrives when it is defined as the engine that delivers these outcomes. When framed this way, it does not need to stretch or retract. It simply evolves with the business.

A big part of determining the future of digital product creation is taking a read on how successfully embedded it’s become within the existing technology ecosystem. This means understanding the shape and the scope of the integration requests seen and worked on this year, of course, but it also means understanding the appetite to make 3D a foundation of the next wave of enterprise technologies as they get rolled out. Based on your hands-on experience of working at major brands like Nike and VF Corporation, where are companies at on this process of embedding and institutionalising DPC – and what do you think it looks like to accelerate that process?

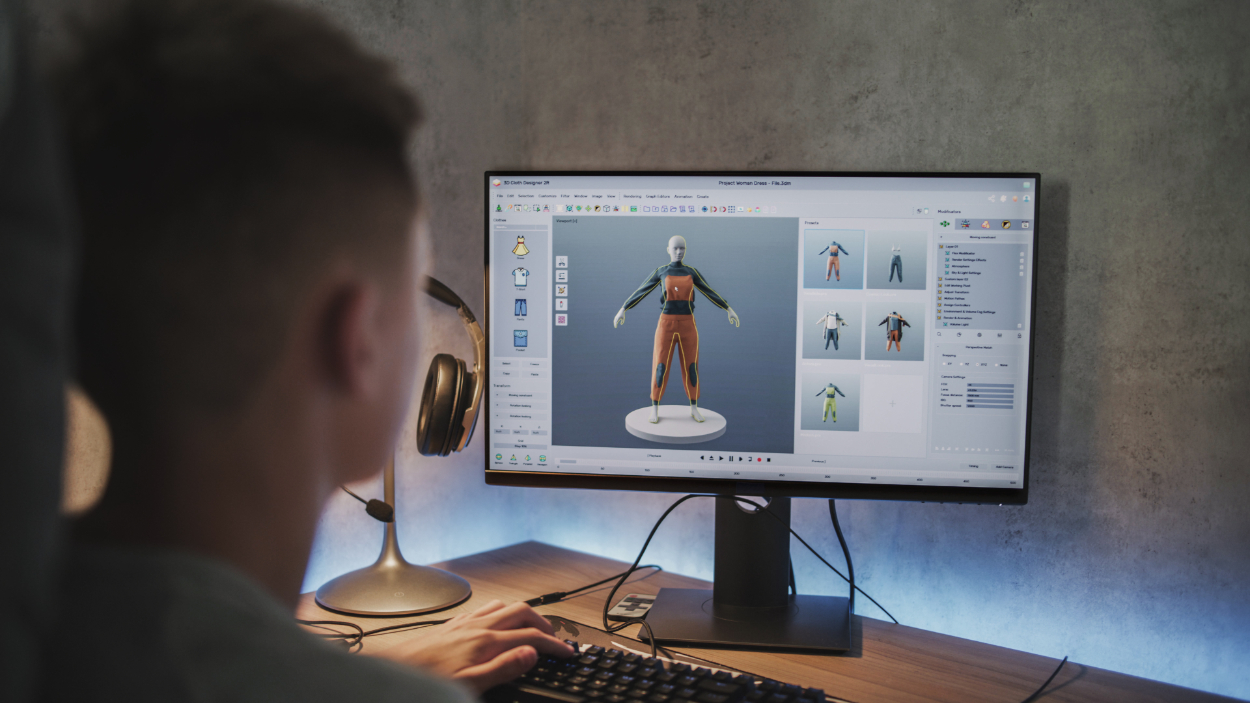

For most of the industry, the foundational layer of Digital Product Creation is already embedded. Digital sampling and visual decision making have become table stakes for companies at one billion dollars in revenue or higher, and for those aspiring to reach that scale. The majority have already made the core investment and are now looking for ways to enhance, scale, or extend its value. This may mean improving the speed of design concepting and quality of product visuals through AI driven tools. It may also mean connecting those visuals to data so that teams in Merchandising and Sales can make better decisions and share them in real time.

For companies that want to accelerate this change, the single most important focus should be to make their efforts human centered to ensure adoption. Adoption is not limited to whether someone is using a tool. It is also about whether teams believe in the new process, understand its purpose, and feel supported in the change. This requires a strong and fully funded organizational change management (OCM) program that operates across all levels of the business. It must go beyond training to include process alignment, leadership communication, and a sense that everyone is moving forward together.

Ease of use is critical. Too many technology projects unintentionally make the process slower or more complex because the original workflow was never benchmarked. Ideally, these projects should result in a net reduction in time and effort for everyone, be enjoyable to use, and automate as much of the process as possible.

There is also a practical point that leaders often overlook. Teams need to understand that supporting innovation will give them a deeper skillset, increase their effectiveness, and allow the company to grow. You want a motivated, experienced team that knows the business, can work at a higher level, and deliver long term value. This becomes nearly impossible if the team believes that a transformation program may also be about headcount reduction. Teams will hesitate to participate in any project that could threaten their roles, and if layoffs follow such a project, the remaining team will be far more resistant to future change.

The bottom line is simple. A DPC strategy that is embedded into the company’s business process model, supported enthusiastically by its people, and aligned to growth and profitability goals is well positioned to succeed.

Last year, we talked to you about automation, and the vision to have one or more parts of the typical DPC pipeline, or the typical product creation process, be able to run with little or manual intervention. Given that a lot of the draw of AI, across sectors and specialisms, is to reduce overheads and automate as much as possible, it feels like that word has taken on a different definition this year. What’s your read on what automation actually means to fashion and beauty companies today? And with an automation hat on, what do you think the ideal end-to-end digital product creation process looks like?

The ideal end-to-end digital product creation process looks different for every company and depends on its business goals, but one theme is consistent across nearly every brand we talk to at Kalypso. Speed is the number one priority. In that sense, automation is a requirement, not a luxury.

The definition of automation has expanded. In the past, people imagined automation as a software function that completed a task on behalf of a user. In 2025, automation also means integration, orchestration, and AI driven capabilities that remove manual rework, eliminate repetitive tasks, and ensure that product information flows cleanly across the enterprise.

Automation can be as simple as a well-designed interface that pre-populates known business data, so a user does not have to type the same details into multiple systems. Or it can be as complex as AI orchestrating supply chain decisions based on material availability, tariffs, production and material costs, capacity, geopolitical stability, speed, sustainability, quality, and many other variables that shift daily. This is exactly where AI driven orchestration becomes valuable. What matters is not the sophistication of the automation, but whether it accelerates decision making along the critical path of the product creation process.

When it comes to Digital Product Creation, the highest value automation is often found in bridging the gaps between systems. Most brands rely on a patchwork of PLM, 3D authoring tools, material and block libraries, render pipelines, vendor portals, merchandising systems, and sales tools. These systems rarely talk to each other. Something as routine as a color change can require hundreds of manual updates, followed by emails, screenshots, re-renders, and version tracking. I have seen situations where a product went into production in the wrong color simply because one system was never updated. That should not be all on the user. Systems need to empower people, not increase the burden.

In an integrated, orchestrated environment, that same color change would automatically propagate to the systems that reference it, notify the people and vendors working with those products, and generate fresh digital imagery wherever needed. Automation protects data integrity as much as it improves speed.

There is one caution. Over-automation is a real risk. I have also seen systems so rigid and automated that they broke the moment an edge case appeared. Life happens. People need the ability to override, adjust, or take a different path when required. Automation must serve real workflows, not force the organization into an inflexible model.

Automation in 2025 is broad. It spans task automation, workflow automation, data automation, AI assisted decision making, and automated metadata generation. The priority is to focus on the parts of the process that sit on the critical path of the product creation process and accelerate decision making without sacrificing accuracy or flexibility. The companies that do this well will unlock speed, reliability, and a scalable product creation model that works at enterprise level.

Vendor and supplier involvement is a critical component of any DPC program. Early on, experienced vendors provide the content needed for evaluation, testing, and validation. As programs scale, vendors supply the capacity required to meet the full needs of the business. Most brands cannot create all digital samples internally, and outsourcing everything to a third party is expensive. The most practical model is to focus internal teams on high value work while enabling vendors to produce the bulk of the digital samples, since the vendor making the physical garment is best positioned to create a high-fidelity digital version.

This does not reduce the need for internal capability. It allows internal teams to focus on work that drives outsized value, such as recoloring, maintaining digital block and last libraries, and building what I call a Digital Sample Room. Historically, physical sample rooms allowed teams to test ideas or produce quick prototypes. A digital sample room plays the same role but at far greater speed, enabling teams to explore concepts, test material changes instantly, and generate fast visuals for decision making.

Bringing vendors along on the journey is essential. I have seen brands ask a vendor about a specific software tool, only to receive an incorrect answer because the question never reached the right person. Most major vendors today have digital capability, and many have had it for ten years or more, although capabilities vary significantly in skill, tool maturity, and consistency. The same level of change management applied internally needs to extend to vendors. They must understand the goals, expectations, and the role they play.

A Digital Sourcing Strategy helps both vendors and internal sourcing teams understand the requirements and importance of DPC. Too often digital sampling is treated as a side show rather than the natural evolution of the sourcing process. The goal should be for digital and physical sampling to sit side by side and eventually be unified within the sourcing function. The only difference to the business should be selecting digital or physical on the prototype request. This requires the same rigor, or more, than is applied to physical sampling. A Digital Sourcing Strategy establishes metrics such as capacity, on time delivery, quality, and accuracy while aligning the digital process with the physical one. Capacity, in particular, is one of the most important metrics and one that brands often overlook. Vendors typically have many customers and a limited number of staff. Building internal speed and capacity takes time, and the same is true for vendors.

The value to the vendor is often overlooked. The most chaotic and least profitable area of a factory is usually the physical sample room. Vendors do not make money on sampling. They make money when a product goes into production. A shift to digital can reduce sample room burden and free resources for production, but only if the brand truly adopts the digital process. I have seen brands order digital samples and still request the same number of physical samples because the entire organization was not aligned with the process change.

Many vendors have been burned by digital efforts that stalled or disappeared. This is why it is critical to visit key vendors, share the strategy early, understand their constraints, and learn what works and what does not in order to build a shared plan for success. Digital capability is not free for the vendor. They must invest in staff, software, hardware, and training to support a brand’s request. Involving partners early and fully is essential. The “make” space is evolving. Vendors are becoming digital development partners. Brands that recognize this and build true partnerships, rather than transactional expectations, will see the greatest success.

Last year we asked about what it means for DPC to scale, and for that scale to be supported by investment, skills, change management, libraries, standards and several other elements. Do we think that scaling has happened in the last year? Do you expect it to happen in 2026? What form will it take? And how will the results be judged across speed, sustainability, consumer engagement, and other metrics?

Scaling will continue if brands see measurable value across multiple teams and functional silos, from concept to consumer. DPC efforts scale when they are established to change the way a company brings product to market, not simply to solve isolated problems. Training, libraries, and standards enable scale, but they only matter if the underlying process delivers business results. For most brands, the real indicators of scale are in business KPIs.

Does the DPC effort:

- reduce the total calendar

- improve product quality

- provide accurate concept and sample visuals earlier

- link product data to visuals to ensure speed and data integrity

- enable Sales to engage accounts earlier

- give Marketing content for richer consumer experiences

- supply eCommerce PDP imagery without photography

During COVID, many DPC efforts expanded rapidly out of necessity. Some contraction afterward was inevitable as companies returned to a more physical way of working. That contraction should not be read as failure. It demonstrated the value DPC can unlock when a business needs to shift to a process that requires speed, clarity, and coordinated decision making.

In 2025, we saw more brands move DPC out of an isolated workflow and into their broader digital transformation programs, connecting it across silos as part of the core business plan. We also saw companies measure success based on improvements in KPIs, not on arbitrary deployment targets. Targets help measure deployment, but they do not measure benefit. This is why a team that digitizes 95 percent of its line but does not impact the calendar or profitability may deliver less value than a team that digitizes 20 percent and improves early sell-in enough to increase profitability by one or two percent. The latter team likely had a far greater impact on the business.

In 2026, I expect this shift toward practical value to continue as companies move past AI hype and focus on integrating AI capabilities alongside traditional DPC. We will see DPC programs connect more directly to integration, orchestration, and automation efforts as brands look to increase efficiency, speed up decision making, and strengthen data integrity. Most importantly, I expect brands to treat organizational change management as a foundational part of their DPC program, with a stronger focus on human-centered approaches to usability. A truly human-centered approach is the single most important lever to ensure adoption

What’s the most useful question that companies can ask themselves, right now, to better understand what they want to accomplish next with 3D – whether that’s driven by their own ambitions, or by changes in the market?

The most useful question a company can ask is: How does your company or program define itself, and will that definition still be relevant in the next five to ten years? The answer to that question determines the staying power of both your brand and your DPC effort.

3D is a powerful solution to many of today’s problems, but so were T-squares and slide rules seventy-five years ago. Many people may not remember these tools, but they were essential to product creation at the time. If you defined yourself as a draftsman, you never would have adopted computer technology. If you defined yourself as a product designer, you always would have been looking for better ways to work faster and with higher quality.

This goes back to the Guy Kawasaki example. How do creators want to define themselves? Are they 3D designers, or are they product visualizers? The difference matters.

The same is true for brands. Do you define yourself as an apparel company, or as an icon of style? As a footwear company, or in service to athletes? The first definition limits you. The second opens nearly endless possibilities for how a company approaches its consumers and how technology can support those goals.

Technology will continue to evolve. We have already seen the shift from 2D CAD to 3D applications, from days long render times to real time visuals. AI now adds a new set of capabilities, but none of these tools are mutually exclusive. They are simply points along a curve of continuous evolution.

My suggestion is to understand how you want to define your company and your creators, then embrace whatever combination of technologies moves you forward, keeps you relevant in the market, and gives your teams the confidence and joy to do their best work.